“If you swing at junk, what’s that pitcher going to throw you?”

It’s a pretty straightforward question. To you or me the answer is obvious just by the wording let alone the concepts. That's because we look at the world differently. We gamers consider the repercussions of our actions more carefully than others. We look at situations from other people’s perspectives; we step outside ourselves. It’s a skill we sharpen each time we sit down to play. Others don’t have it, because it’s a learned behavior, not something built into our brain.

“Junk.”

13 years old, she had paused to consider its implications but answered the question with confidence. She’s smart, the one that always has the radar turned on when she’s on the base pads. Some want to score runs, she needs to. That part of competition is truly instinct -- you can’t teach a player to be a predator. But for seven years she’s been bringing that attitude to the game with a limited set of tools to implement it, and now that she’s 13 she’s in a position to start understanding the tactical and emotional aspects of play on the field instead of just the mechanical. You and I call them the metagame, but the girls on my daughter’s softball team call it revelation. To them it’s profound. To them it’s like moving from two dimensions to three, because they don’t look at the world differently. At least not yet.

For those of you who haven’t played baseball or softball, the real heart of the play occurs between two players – the pitcher and the batter. This is where the intensity is. The pitcher needs to put the ball past the batter, fitting it through this imaginary rectangle about a metre high and half a metre wide. The batter’s armpits and knees mark to top and bottom of that rectangle, the width of a rubber plate on the ground the left and right. Throw the ball past the batter in this “Strike Zone” and it’s called a Strike. Throw the ball past the batter outside the Strike Zone, it’s called a Ball. Three Strikes means the batter sits down in failure, four Balls means the batter gets a free ride to first base and has cleared the biggest hurdle to scoring. In short, the pitcher needs to throw strikes. It’s just that simple.

OK, not THAT simple. It can never be THAT simple. This is where the junk I mentioned comes in. You see, if the batter swings the bat, it’s always a Strike, no matter how bad the pitch. And that’s why I was calling out through the fence to this batter during practice last week when she swung at a pitch up around her eyebrows. It was a complete junk pitch. Even if she had managed to get the bat up on that ball the best she could have done was a crap-ass hit that went nowhere. This girl had given away one of her three Strikes, but she had given away more. She had given away information to the pitcher: “I swing at high pitches that can’t be hit.”

“If you swing at junk, what’s that pitcher going to throw you?”

“Junk.”

When you make them answer a question it sinks in a bit deeper. In this particular case the message was easy to bring – this batter is a pitcher when she’s in the field. She knows how much harder it is to pitch when you’re “behind” the batter, i.e. when you’ve thrown more Balls than Strikes. With each Ball you pitch, pressure mounts and control slips away. As the number of Balls climbs you need to aim closer to the center of that rectangle to reduce risk, and the center is just begging the batter to give that ball one hell of a ride. The job becomes physically and emotionally harder for the pitcher. Conversely, if you have two Strikes on a batter and no Balls, heck, you get to take a little mental break out there. You can play a bit. You can . . . say . . . throw the ball up around the batter’s eyebrows to see if she’s stupid enough to swing. The pressure’s reversed, on the batter now. She’s the one that needs to reduce risk, not you.

At age 7 the lesson was “try to throw a Strike.”

At age 11 the lesson was “try to put some speed on that Strike.”

At age 13 the lesson is “get ahead of the batter and stay there.”

The nature of the game changes as we grow more capable of handling the complexity, and with each batter, we learn a bit more about how the metagame is played. There’s more going on than meets the eye.

Here in America guys raised during the 20th century use baseball as a metaphor for life, and I’ve made it pretty clear that I see game theory as providing remarkably straightforward metaphors for how to succeed in our lives. The first sentence of this article is a pretty clear example of that. But it’s apparent they aren’t clear to the people I deal with in my day-to-day life, and not just the 13-year-olds. Most coaches will not speak of considering another player’s point of view, nor will most business people I deal with, in spite of working in a sales and customer-management role where understanding the motivations and needs of the person across the table is of vital importance. It’s just not something generally considered in the equation. There’s a reason for that – it’s not built-in. It’s not a natural part of us. It’s learned. It’s something we develop over time through experience, and when I say “we” I don’t mean everyone, I mean us. The people reading this. Gamers. To some degree or another, each person learns from competitions and conflicts, the games played be they real or in cardboard over a lifetime. We have the blessing of thousands of plays in a safe environment with little risk. We practice and practice and practice. We learn.

The majority of what we consider social or cultural “instinct” isn’t instinct at all, but learned. These behaviors have been hard-won over millennia. Current science speculates that Homo Sapien’s genome reached its current form and stabilized around 100,000 years ago, but it wasn’t until 30,000-45,000 years ago that the human cultural condition began its transformation into what we consider civilization. “Glacial” describes both the landscape and the rate of man’s progress in this period equally well. Village-sized groupings, the cultivation of crops, hierarchical management structures, codes of ethics, these didn’t appear for more than half of our species’ existence on the planet. Often called the Sapient Paradox, concepts that seem painfully obvious to most of us (“bring water to your plants if it doesn’t rain”) aren’t as straightforward as we think. They needed to be discovered or invented by someone, and then passed down from generation to generation, slowly weaved into the fabric of culture and technology. Tens of thousands of years passed before the rudimentary foundations of civilization took hold. But once they did, the progress could continue. This continued the evolution of man; learned behavior took over when genetic evolution stalled. In fact some scientists view these fundamental cultural concepts as substitute genes in our species, communally owned, but equivalent to genetic mutation. I’m a bit uncomfortable with that concept because it’s far harder to develop (or toss off) chemical-based building blocks than it is knowledge-based ones, but I’m hardly an expert.

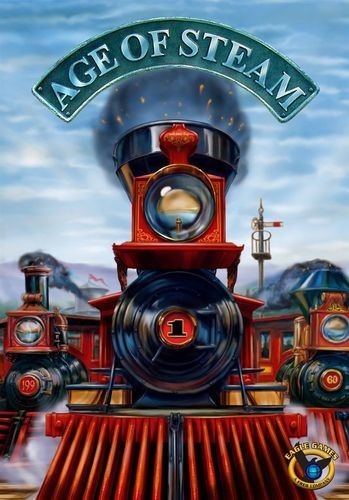

So when we ask questions like “if you swing at junk, what’s that pitcher going to throw you?” or “if you move that piece, what will I have to do in response?” we’re passing along the concepts we’ve learned from Kramer, from Eklund, from Stengel, and from other mentors that understood that dealing with complexity forces us to think in a higher dimension. And maybe, just maybe, we add just a bit more information to the message, moving Homo Sapien one step farther down the path.

S.

Sagrilarus is a monthly columnist for Fortress: Ameritrash.

Games

Games How to resolve AdBlock issue?

How to resolve AdBlock issue?