You might well have seen Jesse Dean’s fantastic article on boardgame reviews and A Few Acres of Snow the other week - it deservedly generated a lot of discussion on the forums. Jesse’s work on this inspired me to have another think about reviewing generally which resulted in a piece on NoHighScores last week about the function of criticism in gaming. That was, deliberately, a generalist piece about game reviewing, its purpose and a comparison to professional criticism in other areas. But I am primarily a board gamer and not a video gamer and whilst I felt that was an important piece to write in terms of theory, I wanted to write a much more definitive one when it came to board gaming.

In that previous piece I lumped board and video game reviews together for the sake of convenience and rather glossed over the differences between them, putting it down entirely to the lack of a professional press on the subject. But this is disingenuous: while video game journalism could benefit from some focus and self-examination it is on the whole in a much better state that board game journalism. I don’t want to possibly preempt Jesse in regards to what he’s going to write with his own survey results but what he told me he found was very scary. And if confirmed what I’d observed myself: that what the board game community seems to be celebrating in terms of reviews are verbatim rules re-writes with a lot of pictures and little or no opinion or analysis, at least if the thumb count on boardgamegeek.com is anything to go by. This is deeply alarming: it’s one thing to suggest that the people who write about board games aren’t stepping up to the plate in terms of quality or pushing the envelope but far more terrifying to contemplate that their audience of supposedly well educated, intelligent gamers is lapping up poor quality material and falling for the most basic traps of mistaking presentation for depth.

I don’t doubt that the source of this blindness is the entrenched amateurism of the game reviewing community, but where that comes from is quite another question. Partly I suspect it’s an issue of perverse pride: the board gaming hobby has never really had a professional press and yet it’s thrived nonetheless, so why not celebrate the amateurism that got us there? This I can relate to - it is after all a similar feeling to the one that lead us to adopt the label “Ameritrash” as an ironic celebration of what others were criticising. I also suspect that the boardgamegeek-as-hobby phenomenon must bear some blame. Such is the devotion that a lot of gamers have to that website and the amateur (as in non-paid) content it carries, that a criticism of material on the basis of it being amateur is seen as a criticism of the parent site and rejected.

But the more I think about it, the more I think the bulk of the problem is simply the peculiar nature of board games and the people that play them. I’ve observed in the past that board games are pretty much unique in the vast annals of Things That Get Reviewed. Normally, a requirement of criticism is that the item in question should have a significant element of subjective appreciation, of user/viewer opinion in other words. Otherwise, what’s the point of having a critic review it for you? If its merits are obvious and objective, you can decide for yourself what to make of it. But a lot of board games do not fall neatly into this category. The mechanics of most board games have clearly defined mathematical roots, and in very many cases - especially true of the modern design paradigm - these can be perceived quite clearly through the obfuscation of theme that the designer has laid on the top. Understanding, appreciating and manipulating these is the basis of a lot of game strategy. This element of game design is quite clearly not subjective: if it’s mathematical one can make clear and unambiguous judgements on whether it has succeeded or failed. And yet a game which is nothing but mathematical analysis would be, to a gamer of almost any taste, a poor game. The added value in games comes from elsewhere, often from interacting from your fellow players but also from drama, tension, theme, narrative, even artwork and production. These obviously are subjective elements when it comes to criticism. In other game genres such as video and role-playing, although the games contain mathematical elements, the pleasure of the experience is entirely independent of understanding them so the critic can concentrate on the subjective. So while properly balancing the objective and subjective is a key goal of all form of criticism, nowhere is it so vital as in board gaming, where the success of the product itself is equally dependent on maintaining that same difficult, challenging balance.

And stepping up to address this unique blend of art, maths and entertainment we have the board gaming community. Who are mostly geeks. And geeks, of course, tend to have strong backgrounds in maths and science where they’re taught that the only proper way to analyse something is to do it objectively, to collect evidence and use that to support and argument in favour of their thesis. This is not meant as an insult: I am a geek, and an ex-scientist, and the expositional style of my writing has all the hallmarks of having been taught and re-taught that particular manner of analysing something. Indeed as a method of constructing an argument for an opinion or editorial piece it has an awful lot of merit. But when it comes to the gentler arts of criticism it leads us up a blind alley, a particularly pernicious blind alley where we start with the only certifiably objective parts of a game - its rules - and build up from there, often failing to get further than making a very basic connection between mechanics and quality. As a reviewer, I’ve been struggling to get out of this trap for years and only recently have I felt like I’ve been starting to succeed.

And having to tackle this unique balance of objective and subjective analysis is simply the first unusual hurdle that we, as board game reviewers, face. Another, which Jesse touched on in his piece, is time. A film critic has perhaps to sink a maximum of six or eight hours into experiencing the product he’s going to review before he understands it enough to start writing. A video games journalist or literary critic might expect to spend 20 hours to do the same thing. All three critics can get in the required hours alone, at a time and place that suits their schedule. Pity, then, the poor board game reviewer who not only has to find anything up to and above that same 20 hours to get to grips with his subject matter, but who in most cases has to find one, two, five other people to experience it with whose schedule fits his own. What hope has an amateur reviewer to find the time to do this properly outside of work and family time? Add to this the speed with which publishers seem to be able to churn out board games nowadays, which is quite ridiculously short compared to the development time in man-hours of a AAA video game or blockbuster film, and you’ve got an overload of product and not enough opportunities to properly get to grips with it. No wonder reviewers miss deeply buried gameplay problems such as those with A Few Acres of Snow, and no wonder they so rarely find the time to revisit and re-analyse old classics where issues have been uncovered and explored by die-hard players.

A further issue is that we’re all game whores, and we have a tendency to love games in spite of their flaws. Or, to be more accurate, that it’s actually relatively easy to design a moderately entertaining board game compared to an immersive video game or thrilling novel. The “relatively” bit is important here: I’m not decrying the skill of game designers, especially not since I’ve never really tried to design a game myself, just saying that it’s a shorter slope than it is for other media. Anyway the upshot is that the majority of games that make it on to market are pretty fun to play, even if they perhaps lack originality or longevity. And because we’re game whores we tend to give titles that conform to this average the benefit of the doubt and say that they’re basically good and worthwhile when what we should be doing is revising the scale to say that average is just that, average and not good just because it’s fun for a couple of sessions.

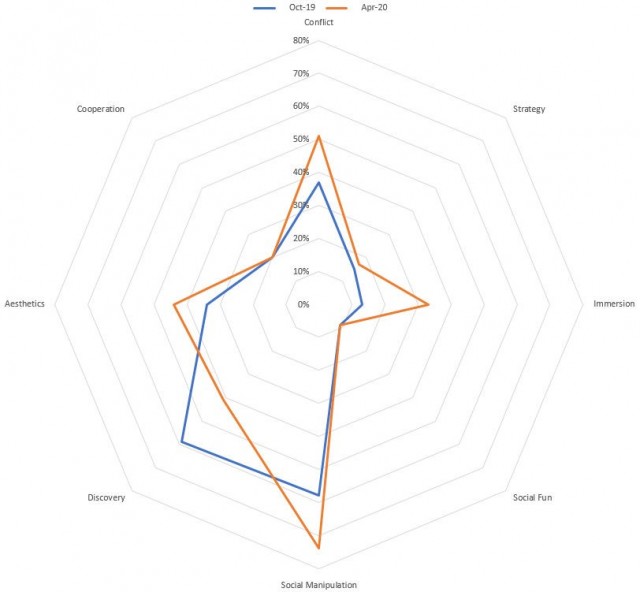

The final barrier is the extraordinarily wide polarisation of taste in the board gaming community. In other areas of criticism there is general agreement over what is genuinely great, and what is not. If you picked a critic’s list of her top ten video games for your platform of choice, for example, the chances are you’d probably enjoy the majority of them whatever your particular taste in games. Likewise if you sat through some recommendations of a film or literary critic. But in board gaming one man’s meat is genuinely another's poison. The standard geek lack of empathy exacerbates this problem, a seeming inability to see that what constitutes “fun” in a board game varies very widely depending on the player and the resultant preaching that playing one type of game or another is somehow wrong, and that this point can somehow be proved beyond doubt with a of scientific analysis of the mechanics.

So basically what I’m trying to say is that the reviewing of board games presents a quite unique set of challenges, which the fan base from which reviewers are drawn is quite uniquely ill-suited to meeting. That’s a difficult conundrum, from which it’s difficult to see any other meaningful escape route other than the establishment of a professional press. But there’s always the hope that simply highlighting the issues and promoting discussion of them will be enough to move things forward inch by inch into a better place. The first step is to understand that in celebrating amateurism, there’s an enormous gulf between being an amateur and writing like one, and it’s about time that more writers stepped up and at least tried to cross that chasm.

Games

Games How to resolve AdBlock issue?

How to resolve AdBlock issue?