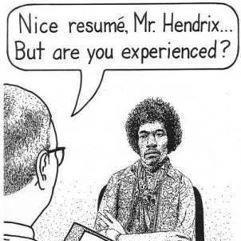

“It’s more of an experience game.”

“It’s more of an experience game.”

Gamers have heard this phrase many times, which means it might be borderline meaningless. When I hear it, it conjures up a game where the process of playing it is inherently more important than the final result of who wins. The phrase “experience game” is sometimes used euphemistically for a game that’s a lot of fun but might not meet some nebulous mechanical standard. In that sense it functions as a little of a backhanded compliment, though not necessarily.

I know that I’ve used the phrase many times to describe a game like Tales of the Arabian Nights or Magical Athlete. Those are pretty elementary games, mechanically speaking. They feature a heavy dependence on die rolls and downplay the agency of the player. Such games are simple enough that someone who really likes to think and plan moves won’t get much out of them, but the simplicity also creates a setting where who wins is ultimately unimportant compared to the chit-chat and goofy stories that result. I’ve also heard the term applied to games that take an entire day. If you spend 12 hours playing Diplomacy, that experience will stand out compared to the hundreds of hour-long games you’ve played. Just the other day I heard it used to describe Kolejka, the Polish game about waiting in line to do your shopping. (Trust me, it’s much better than it sounds.)

So the phrase means different things to different people. But my question is, what game isn’t an experience game? The way I have always used the phrase strikes me as narrow, especially in light of some other stuff I’ve written. What is a board game if not an experience? If I buy a copy of Princes of Florence and never play it, it might be a game but I cannot speak to its quality at all. Until we sit down and plow through the rules and play it, it’s just a box of components. When we sit down to enjoy a game together, whatever rating of qualifier we apply to it isn’t for the game itself but rather for the experience.

That doesn’t mean that there aren’t good and bad games, just that we’re not really judging the game itself. If I sit down to a game of Goa, I probably won’t enjoy myself. It’ll help to have some good friends at the table, but I find that game altogether unpleasant. That’s not based on any particular rule or mechanic, but on the emotions those mechanics bring up in us when I perform them. After all, any mechanic can be used to good effect if it’s in the right game. Why did Shadows Over Camelot falter for me when Battlestar Galactica soared? They both used the traitor mechanic, but the way it was used in BSG was far more compelling. We like games not because of what they make us do, but because of how they make us feel when we do them. That might be the challenge of working out a complicated logistical problem or the thrill of rolling a dice to see if you killed a monster, but both are emotional responses. And of course, the preferences and personalities we bring to the table have a profound effect on the gaming experience.

In that sense all games are actually experiences. You cannot judge a game’s quality in the abstract. Every game lives and dies on the experience it provides. That’s why there are some games that I simply will not play with some people. I’m not playing Talisman with people who won’t buy in, just as I know I would only be a drag on that table playing 7 Wonders. A lot of gamers will be uncomfortable with this, because it moves the hobby out of the familiar territory of numbers and BGG rankings, and into the squishy realm of humanity. Not everyone is comfortable with such a relativistic view of board gaming.

But I don’t think that discomfort comes from some robot-like fear of emotion. I think it’s because when a game exists in the realm of human experience it requires us to think about how we affect that experience. When we view our gaming experientially, it actually dictates how we must act around the table. While it’s true I can’t control what people feel and do, there is a small slice of the experience that I am responsible for. That means I can’t sit there pouting or complaining like a child if I don’t much care for the game itself. Griping won’t get me out of playing, it’ll only make the rest of the game suck for everyone else. That also means that I really shouldn’t start acting smug if I’m winning a game. All that does it make other people feel stupid and make me look like I care too much about winning. These items are more ways that I perceive my own behavior might affect the experience for everyone else. I don’t really intend to sermonize. It’s just that when I consider that the bulk of my gaming is dictated by the experience around the table, I have to acknowledge that a big part of that comes from the human element. And if that’s true, it just means that I need to think about my own actions affect the experience of other people.

That sound I heard was all of my readers saying, “No kidding, genius.” Like many similar thoughts, this one seems ridiculously obvious when I’m on this side. But I had never considered the idea that every game is really an “experience game,” because every game is judged on its experience. And acknowledging the human as being a part of that experience, that’s why you don’t act like a jerk to everyone else around the table. In practice it doesn’t change a lot for me, since I tend to only pursue games I like and I do my best to not be “that guy.” But in theory, it does shift the emphasis away from what I can get out of it, and more towards what all of us can get out of it. The experience of playing a game is a communal one, and I’m not sure I’ve always treated it that way.

Nate Owens is a weekly columnist for Fortress: Ameritrash. He drinks too much coffee and likes the Star Wars prequels. You can read more of his mental illness at The Rumpus Room.

Games

Games How to resolve AdBlock issue?

How to resolve AdBlock issue?