A short while back we had a little discussion session, sparked by articles from Matt Drake and Michael Barnes , about game reviewing. There were some very good points made about the parlous state of game reviewing in this hobby, the reasons why it's in such a state and some suggestions as to what we can do about it. But there was one viewpoint, expressed by both article authors and supported by a lot of people on this site, that I absolutely could not swallow. And that is the idea that by saying that a game is "not for me" rather than saying "this is a bad game" the reviewer has somehow sidestepped their responsibility to the reading public to deliver an actual opinion about a game and is likely doing so only to avoid offending a portion of their audience and/or the game manfuacturer. This isn't to say I disagree with the general thrust of both articles, because I don't, but by putting the focus squarely on the expression of personal opinion in a review the writers were, I think, doing a grave disservice to their attempts to improve the state of review writing in the games industry. People have often accused the opinions expressed on this site of being divisive, mostly wrongly in my view, but if ever there was an viewpoint to which that sticks, it's the one I'm attempting to disabuse here.

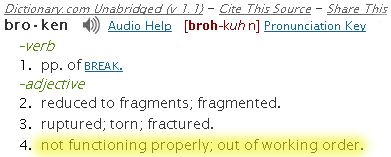

Let me make a confession - I'm a game whore. As a general rule I'll play almost any game, even games I don't much like, in preference to not playing a game. It came as something of a surprise to me when I eventually realised that a lot of gamers don't feel like that and instead dislike a fairly large number of games with a passion which would see them sitting and watch paint dry rather than enduring a play. There are some games that evoke that feeling for me, but they're very few, and they are for the most part games to which I'd attach the over used and much abused term "broken". Considering this term is so over used and much abused, let's spend a bit of time examining it, based on the definition that I gave at the start of the article.

A short while back we had a little discussion session, sparked by articles from Matt Drake and Michael Barnes , about game reviewing. There were some very good points made about the parlous state of game reviewing in this hobby, the reasons why it's in such a state and some suggestions as to what we can do about it. But there was one viewpoint, expressed by both article authors and supported by a lot of people on this site, that I absolutely could not swallow. And that is the idea that by saying that a game is "not for me" rather than saying "this is a bad game" the reviewer has somehow sidestepped their responsibility to the reading public to deliver an actual opinion about a game and is likely doing so only to avoid offending a portion of their audience and/or the game manfuacturer. This isn't to say I disagree with the general thrust of both articles, because I don't, but by putting the focus squarely on the expression of personal opinion in a review the writers were, I think, doing a grave disservice to their attempts to improve the state of review writing in the games industry. People have often accused the opinions expressed on this site of being divisive, mostly wrongly in my view, but if ever there was an viewpoint to which that sticks, it's the one I'm attempting to disabuse here.

Let me make a confession - I'm a game whore. As a general rule I'll play almost any game, even games I don't much like, in preference to not playing a game. It came as something of a surprise to me when I eventually realised that a lot of gamers don't feel like that and instead dislike a fairly large number of games with a passion which would see them sitting and watch paint dry rather than enduring a play. There are some games that evoke that feeling for me, but they're very few, and they are for the most part games to which I'd attach the over used and much abused term "broken". Considering this term is so over used and much abused, let's spend a bit of time examining it, based on the definition that I gave at the start of the article.The given definition seems pretty clear to me - it's something that doesn't work. Doesn't work as in does do what one would expect it to do. Seems to me that people play games primarily for three reasons, although the proprtion of importance of these three reasons will vary greatly with the individual: games are fun, they provide a strategic challenge and a structured social framework. So by this measure a game would have to fail to deliver in any way on any single one of these three criteria. I contend that it's actually pretty hard to create anything that merits the description "game" which fails so spectacularly - games which are actually 'broken' are in fact extremely rare. The word seems to have become used as a shorthand way of saying that "I don't like this game" which isn't the same as saying "virtually no-one would like this game" which is what I'd expect of a game which was truly broken. A game is not broken just because you, personally, can't find the time to play it. A game is not broken just because you, personally, value a less or more random experience than the game provides. A game is not broken just because you, personally, think it has implemented it's theme too heavily or not enough. A game is not broken just because you, personally, don't like it.

But I've already allowed that some broken games do exist. So what criteria can we lay down to describe a game which is truly broken? To deserve the term in my opinion a game has to exhibit one of two problems. Firstly, it must have a near-guaranteed outcome regardless of the choices made by the players during the game. Let's be clear here - this isn't the same thing as saying that a game with few or no choices is broken because a lot of popular gambling games have few or no choices but can still be a lot of fun. And we should also be clear that this problem can arise in a variety of ways - it might be that a game is so simple it's nearly always a draw or that it's so badly balanaced that one play position almost always wins. The second criteria that can break a game is considerably more subjective - that it's far too long and/or complicated to be worth spending time learning and/or playing considering the game experience it delivers. I will re-iterate that this is categorically not the same as deriding a game as broken because you're too time-poor to get involved in it. Take Risk - The Lord of the Rings as a fantastic example of what I mean: the game runs 2-3 hours but probably a full 75% of games can will be decided by the dice rolls in the closing rounds that determine who has the last turn before the game ends. So effectively it's a five-minute gambling game without any decisions stretched out to require several hours, fancy components and a multi-page rule booklet.

What I'm driving at here, if it's not clear yet, is that beyond the realms of games for very young children (for which the criteria have as much to do with learning the social etiquette of game playing as they do with gaving fun) there are a vanishingly small number of games which are actually "broken". And if a game is not broken, I contend, there will be at the very least a significant minority of people in the gaming community who will enjoy playing it. And if there are a decent number of people around who might well enjoy the game, then writing a review saying "this is a bad game" rather than "this game is not for me" about any game which isn't actually broken or nearly broken is doing a lot of people as bad a disservice as writing a game which fails to give any viewpoint at all.

I can quote many examples to make this point entirely clear. Take Magic Realm. For me it presents some risk/reward gameplay which isn't especially interesting and fails to be any better than a lot of other adventure boardgames in terms of narrative. As a result it runs dangerously close to coming under my second definition of a broken game. I wouldn't describe it as broken, but I do think it's pretty bad. But Michael Barnes - and a lot of other people - love it. So would Michael really agree that it'd be useful if I presented a review which simply lashed the game, failed to mention any of the things some people like about it and simply derided it as "bad" and "broken"? He, in turn, intensely dislikes the Ticket to Ride games which I quite enjoyed, although I burnt out on them pretty quickly. I know a couple of the other AT staff writers also like the Tt:R games. So are they really "bad", "broken" games? Or are these both simply examples of games which are, truly "not for everyone"?

I don't think it's very difficult to differentiate between games that are broken and those that the reviewer sees as being very bad. For starters you could apply my criteria for a broken game. You could go looking for the opinions of people who do like the game. I'll bet that any experienced reviewer could guess why and how a game might have some appeal to some people just from reading the rules. It's no different from watching an action film and thinking that hey, while you much prefer documentaries you'll allow that the chase sequences would be pretty exciting for those that liked big, loud films. The fact that it's pretty trivial to make this differentiation means that one can write a review of a game one dislikes intensley which conforms to all the things that are being called for - it can be honest, it can be brutal, it can express with great clarity why you hate the game so - whilst still making clear why and how the game might have some appeal to some people. And in summing up you can - indeed you're almost obliged to - describe the game with some variant on the phrase "not for everyone" and you've done so without sacrificing one iota of your reviewers conciensce or, indeed the opportunity for offending people that you feel deserve offending.

Before we finish, let's flip this on its head. Instead of my pointing out what breaks a game, let me tell you what it is that I look for when, in the process of working out whether or not I want to buy a given game, I read a review. I want to know something about the mechanics it employs. I want to know something about the logistics of game play - average time, sweet spot for player numbers, physical space required - things which get overlooked in an astonishing number of reviews. I want to know what sorts of skills the game taxes - is it a maths-fest, a negotiation game or a risk management game for example. I find it useful to know if there are any other games the reviewer thinks are similar so I can either make a comparison myself if I know one of those games or perhaps check one out if I think the current game I'm looking at doesn't cut the mustard. Finally, and probably most importantly, I want to know how the game feels to play - is it tense and exciting, brain-burning, narrative-driven and so on. If you check back along that list, I reckon one could write a review which answered all those questions for me without the reviewer once saying whether they liked the game or not. It'd be hard and, in truth, the result would be so lifeless that I doubt I could struggle through reading it. But a review should be as much, if not more, about informing the game-playing public about the experience of playing the game as it should be about providing entertainment.

In his original article Michael makes a point about a "different horses for different courses" model being inappropriate for all forms of artistic, literary or media critique because ultimately these forms are about how they appeal to individual understanding, so by failing to give a personal viewpoint a critic has failed in his job. What this argument doesn't take into account is that across these different forms there are different levels of the importance of technical achievement. In modern art, and to a lesser extent classical art, technical merit is largely irrelevant to the value of the work. If this were not so, how could we have arrived at a time when artists commonly commision others to do their technical work for them, yet still recieve 100% of the praise for the resulting art? Next down the scale is literary criticism which is still very much in the eye of the beholder but where we can all agree on basic rules of style for forming poetry and prose. When it comes to films, music and video games we're in a different world entirely. Here there are very much technical standards that we can all agree on. Whilst we might disagree on the direction in which a given actor has chosen to take a character, we can all agree on how successfully the actor has managed to portray that character - that's a matter of technical merit, even if it's a "technique" which is hard to quantify. One can make similar arguments about more mechanical aspects of these media such as cinematography and special effects. This doesn't remove the value of a personal opinion from a critical piece on a film or game, but it does open up the possibility of a critic writing something which says "I don't like this, but I admire its technical merits". Ever wondered why it's common for a critic to give a numeric rating to a film or computer game but rare for a book or visual artwork? Board games are even further down that line than films - there are very much specific standards that we can agree on, making a critical standpoint which says "It's not for me, but ..." even more valid.

This might seem like a laboured way in which to make a relatively trivial point, but for me it's an important one. Just because a review makes an attempt to be even handed and ends up extolling some of the virtues of the game as well as the bad points is categorically not a sign that the reviewer has ducked out of giving an opinion in the interests of not offending anyone. In making this statement I am not defending the sorts of lazy, meaningless reviews that people were holding up to scrutiny in the first place in the wake of the whole Black Ops giveaway/sale thing. I am not defending the practice of bribing reviewers with free games in the hopes of getting a favourable review and of reviewers spinelessly conforming to the viewpoint the publisher expects of them. It's just that around here I think we sometimes conflate attempts at presenting a balanced viewpoint with presenting no viewpoint. I don't believe that's true, and this is my stab at attempting to rectify the balance.

Games

Games How to resolve AdBlock issue?

How to resolve AdBlock issue?