Britain is pockmarked with standing stones. On a recent holiday we passed them in a dozen different sites. High on windy hillsides or perched above rocky bays, the waves seething over jagged rocks beneath. I love to touch them, to touch my history. They feel like the bones of the country, smooth yet pitted.

Traces of their makers cover the landscape like a swirling tattoo. Hill forts, barrows, buried hoards of gold. Yet they do not speak to me. Their brash Roman conquerors do. Julius Caeser wrote books. His legionaries wrote letters, pleading for thick socks and underthings against the bitter British climate. I had long hoped I might find the voices of the Britons in some forgotten thing. A squashed coin perhaps, or a rusted sword hilt.

I have found them now, in a most unexpected place. In a box, fashioned from green wood and decorated with gaudy stickers.

They are not always Britons. Sometimes they masquerade as Gauls or ancient Germans. It matters little. All these peoples shared a culture, all contributed to my culture and all them were silenced. Their voices drowned out by the shouting of their conqueror, Rome.

At first, Commands & Colors: Ancients seemed a strange place to find them. With its emphasis on lines, leaders and structure, it felt a poor fit for this rabble of proud barbarians. They should be rushing the enemy, half naked and ululating, not trying to scrabble together adjacent units for a line command. I couldn't see how the system would accommodate them without a lot of extra rules.

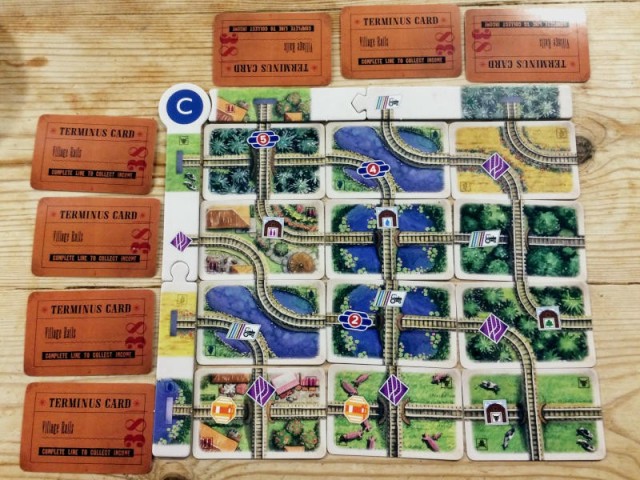

The answer is simple. Barbarian armies rely on light units, chariots and warriors. Against them, their Roman empire foes are from the legionary era, with its backbone of heavy infantry. Embellished with the new Marian Legions rule which gives them missile fire to represent their pilums, they are a terrifying force.

The result is a perfect ballet of asymmetry. The Roman army can function like a well oiled machine - providing its commander has a bit of luck and a lot of skill with command cards. The barbarians can't hope to face them in formal battle lines. Instead they must rely on their maneuverability, flexibility and the momentum advance of the warrior units.

Not that it does all that much good. It's difficult in many of the scenarios for the barbarians to win. Trying offers a tiny taste of the terror they must have felt. Rough men with rough weapons charging down the most effective military machine of the ancient world. A human tide breaking on a wall of iron.

You might ask why they bothered. The vast contrast between the stickers and capabilities of the two armies offers a clue. These cultures were profoundly different. The barbarians fought to protect those differences. Because they wanted to worship at stone circles under the open sky, not austere temples of marble.

It's not all about the barbarians. Julius Caesar makes an appearance, alongside his formidable tenth legion. There are special rules to make them appropriately fearsome. There is Spartacus, too, and other slave revolts. They're allowed to roll burning logs onto the enemy in a unique area-effect attack. When it's resolved, the slaves themselves lose a block which has to be one of the most appallingly expressive rules I've ever seen. It reeks of desperation; and woodsmoke.

The Romans get their own scenario booklet, detailing the brutal civil wars the marked the end of the republic. These are similar to the existing scenarios of Greece and the Punic Wars in terms of the forces offered. There are some new terrain tiles to throw in.

And even though they happened far away, they have their own immediacy. These were not far-flung conflicts in Africa or private violence between city states. These battles were pivotal in western history. Had they gone otherwise, it could have been Mark Antony or Pompey wading ashore at Dover, or no-one at all.

There are over forty new scenarios here. Thanks to subtle use of terrain and novel elements, they offer huge diversity. In place of the blank battlefields of the original there are marshes and coasts, villages and ramparts. Rather than faceless light, medium, heavy toops there are the stoic Legionaries of popular imagination. Waiting in silence as painted devils descend on them from the fog.

I have played wargames where British soldiers fought on British soil from the Wars of the Roses to Operation Sealion. But none felt as personal or evocative as this. With a minimum of rules, these expansion scenarios give voice to a long dead people. They allow us to touch their vanished world like we touch their standing stones. There's little more one can ask for a conflict simulation.

Games

Games How to resolve AdBlock issue?

How to resolve AdBlock issue?