According to some literary theory, an author's interpretation of their own work is no more or less valid than that of any reader. If we apply the same to game design, what do we make of designer Jim Felli's insistence that Bemused is not a social deduction game? It looks like one, smells like one and plays like one so, in the face of so much evidence, we can only put this down to a case of madness, right?

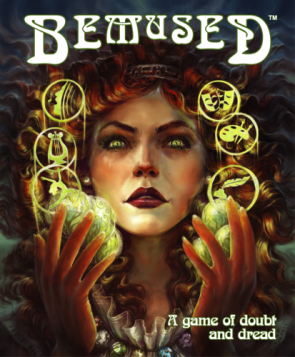

Fittingly, Bemused is itself a game of madness. Players take the role of divine beings who have chosen to inspire a randomly-assigned artist. You also get a randomly-assigned - and hidden - secret and "gemina". This is a fancy name for another artist that has some relationship with yours, and the secret defines what that relationship is. Perhaps you're jealous and want to drive them mad, or consumed by love and want them not to die. Whatever it is, if the game ends with your gemina in the desired state, you get some points. So: it's obviously a social deduction game.

And indeed it is, which makes the designer wrong. Except he isn't. Because here's the thing about Bemused. It's a social deduction game, but it's also a whole lot more other things beside.

Although you want to elevate your artist, the actual play revolves around trying to knobble the opposition. You do this by playing Doubt and Dread cards on them. The former have a colour, and can only get played on the matching artist, which slowly drives them mad. The latter can be played on anyone and will quickly kill them. Not that there's any player elimination here, since you can carry on playing as a ghost and the game is so fast it barely matters either way.

Turns out that the best way to win the game is not to die: the bonus points from your secret are more like a tie-breaker. If you do die then your best hope is to ensure that as many other players pass into the ethereal realm with you. Usefully, dead players get extra Dread cards to play, making this a very real possibility. The result, as you might expect, is a brutal free-for-all with players conniving and conspiring to pin Doubt and Dread on each other. If you want to win, there's no room for compassion or mercy: you join in every dogpile that crops up, and hope no-one sticks one on you.

This, of course, is much like a lot of diplomatic and bash the leader games. Bemused has two things that make it stand out from the crowd. First is that social deduction aspect we've already mentioned, adding an extra frisson of doubt to every fragile alliance. Second is its speed, with games often wrapping within ten or twenty minutes. It's biggest issue is that it needs at least four to play and, ideally, needs more. If you like dishing pain on other players, Bemused lets you dish a lot of pain on a lot of people in a short space of time.

Yet we're still not done describing what the game is. Every artist in the game has a special ability. The Singer can remove Dread cards, for example, while The Dancer can move them around from one target to another. This adds an aspect of simple strategy to the game, making best use of your power to stave off the inevitable lunacy and death. Plus, you can take a Dread card by choice and reveal your gemina, gaining their power too. Dread is nasty, and keeping Secrets is useful, but sometimes it's worth it. Knowing when is a key skill for success.

When the players start to get to grips with how this game works, these powers actually begin to form a simple economy. Together with the cards, they're the leverage on which you threaten, cajole and bargain with other players. The Thespian working with the Singer, for example, can change Doubt into Dread and remove Dread, a powerful combination indeed.

What starts out looking like a social deduction game proves, in the final reckoning, very hard to classify. It's part social game, part strategy, part economic yet it's also all hard edges and meanness. It's plays at the speed of a filler but has more depth than most. It's a friendly party game that's bound to make you enemies. And this confusion, I suspect, is exactly what the designer intended all along. Telling us all it's not a social deduction game is a part-truth, but the falsity of it is all part of the grand game that he's created.

Games

Games How to resolve AdBlock issue?

How to resolve AdBlock issue?