It is a lovely book, the size of a standard hardback with an embossed cover and three bright ribbons to mark reference places. But when I open the book the I get the loveliest surprise of all. Two six-sided dice tumble onto my lap from their hiding place, a die-cut hole in every book page. They’re cheap, with an owl instead of a one, and the thought occurs that this falling out ritual will, in time, become quite annoying. But right now, I’m in ecstasy.

So, of course, I dive straight into the content. And that’s lovely, too, but it comes as a bit of a shock to this RPG veteran. Pretty much all the rules of the game are: roll one dice against a difficulty of two to six. If you have a trait that helps or a flaw that hinders, roll two and take the best/worst result. If you have an item that helps, add one. There’s no combat, no detail, and nothing to help people new to role-playing work with this skimpy scaffold, even though it's clearly aimed at them.

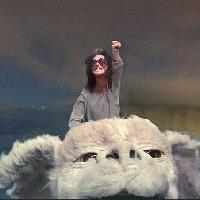

When I sit the kids down to play, they blunder right into the second trap in the rules. Your traits and flaws depend in part on what “kin” you choose: human, dwarf or rogue goblin. These all make sense given the cult film that inspired the game. But you can also choose “horned beast” or “knight of yore”, kins that are based on single characters from the film. These seem like a clumsy overreach, weak fan service that will lead to confusing lore and a role-playing dead end.

So, of course, they choose these two kins for their characters. And, as I’d feared, the party is a carbon copy of Ludo and Sir Diddymus from the film. But as the initial scenes unfold, it’s clear they’re having a great time adventuring on these crutches. It seems to help put them confidently into this unknown space which is both like, and unlike, one of their favourite films. They decide that both want to become knights and that the Goblin King has stolen the sword they need to become knighted.

Given the simplicity of the rules, the meat of the lovely book is the Labyrinth itself. That’s right: this is a self-contained set of rules and attached adventure in one. I, as the Goblin King running the game, have a few more rules to digest covering exploration. The Labyrinth is broken into 99 scenes. When the players navigate one, they roll a dice and move forward that many scenes. But sometimes you have to backtrack. If they do well, they get to “bookmark” a scene which means they won’t have to backtrack. Do badly and they’ll lose one of the thirteen hours they have to complete the quest.

Jovial as I am in presenting the first scene, inside I’m nervous. I haven’t read many of the 99 scenes and, indeed, there’s little point in doing so. No GM would remember them, and given the random progress through them, you can’t plan a session in advance. All I can do is use those bright bookmarks to track our progress, speed read when we flip to each new two-page scene, and hope.

I can’t tell you very much about our adventure for fear of spoilers. But I can say that most of my fears were unfounded. The simple mechanics are enough to support the material. Two pages is not a lot to skim at speed. And once introduced, I have time to double-check the details while the kids decide what to do. Most pages have tables of names or scenery or other variables you can roll on for spice or quick ideas to fire your imagination. Once I’m in the groove, it becomes second nature, scribbling notes as I go to see if I can tie future scenes to previous events for a sense of consistency. But I wonder how the neophytes this simple system seems made for might cope.

The scenes themselves are, on the whole, fantastic. A few are repeats of scenes from the film, but with a table-based twist. My players meet goblins antagonising a bound victim: in the original, this is the beast Ludo, but in our version, it’s a big-nosed gangly creature called “Sebastio”. Most are new and varied, spanning puzzles to exploration to opportunities for role-playing. Yet they all fit in with the crazed eighties aesthetic we’d expect of the Labyrinth and its animatronic inhabitants. Each takes ten or twenty minutes to play through.

As a good GM, I do my best to slice away the time to ensure an exciting ending in the Goblin King’s castle. But when we get there, the game seems determined to thwart me. Again, without giving too much away, the rules as written would seem to make it almost impossible for the players to corner the Goblin King. I wing it as best I can but even when they catch up, with combat or much to work with, it’s anti-climatic. They get their sword but it’s a weak end to a fantastic adventure.

Is that my fault, or a fault of the book itself? Both, of course. But again I can’t help but imagine how the apparent target audience of new gamers would cope with framing the tale. There’s a further sting too: you can't skip some of those 99 scenes, so you'll encounter them on every playthrough. So this isn’t a game that can be re-run without a lot of work on the part of the GM. That’s true of every scenario, but this one comes with a ton of great content players will miss in a single game.

As I pack those wonderful, annoying dice back into their hidey-hole, I reflect on what a bizarre chimaera Labyrinth is. A game for neophytes that requires experience to run, a catalogue of fascinating mysteries most players will never see. But then, when you look at the chimaeras Jim Henson and David Bowie put onto our screens, perhaps this game is a fitting tribute to them after all.

Games

Games How to resolve AdBlock issue?

How to resolve AdBlock issue?