It remains a constant source of astonishment how much game you can get out of a mere twenty-six letters. Word games have been a constant through the history of games, always surprising us with new turns of invention. And a good thing too: they’re easy to learn and quick to play, based on concepts we all understand. Yet for all that happy history, you’ve never seen a word game like Inkling.

Each player gets a clue card, which lists six words worth from one to three points, and eight letter cards. Except these aren’t ordinary letter cards. All are printed in a vague, stencil-like typeface full of curves and gaps. Arranging them together looks like bi tso fb rok engl a ss, not any ordinary line of type you can imagine. And there, in the gaps, is Inkling’s genius.

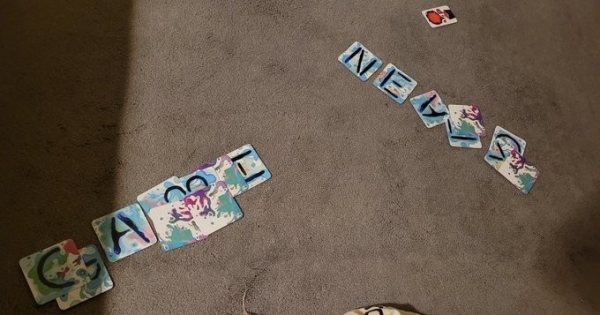

Your task is to use your cards to communicate to other players one or more of the words on your clue card. Let’s say one of them is “game” but your hand consists of the letters C, D, A, B, H and some other cards. Not a lot of help, you’ll be thinking as you glance down, puzzled at the puzzle of letters. But you twist and turn and flip and ideas begin to form.

You put down the C, then pivot the D on its side and tuck it under, so that the curve of the D looks a little like the overhook on a G. A is fine as is. To make the M, you turn the B curves upward and cover the lower half with another card, flipped over to its patterned back. The E is more difficult so you take H, turned on its side and part-covered with another card so it looks like a C and trust to the other player’s judgement. “Gamc” isn’t a word, after all.

Can you guess what these two words are?

It’s hard to overstate what ingenious solutions Inkling allows you to come up with. Using the backs of turned-over cards as blank letters is an obvious one. I’ve seen words curved in a graceful bow so that someone could arrange a Z from three cards without making it look too much like an N. I’ve seen acronyms, shortenings and phonetics. I’ve even seen the cards used to make pictograms although those are very difficult to guess.

You play for three rounds, which tends to be very quick, getting a selection of new cards after each. Then you tot up the points values of the words you’ve guessed, plus those from players who’ve correctly guessed your words. It’s a neat circle that rewards good clues as well as good deduction. Puzzling over what other players have left for you is as much fun as creating your own clues. Tracing the lines, wondering what they represent, what the blanks and symbols could be. There's that delicious forbidden fruit of wanting to know and wanting to give it away while knowing full well it's now allowed. The revelations are often as funny as they can be frustrating.

As fun as Inkling is in short bursts, its simplicity becomes its undoing. There are only so many ways you can rearrange your cards to make them look like other letters, after all. Yet even after enthusiasm has begun to wane, it remains worth bursting out like a blast of fresh air to clear the pipes. There are lots of word games but very few games that reward genuine creativity and Inkling captures the best of both.

Games

Games How to resolve AdBlock issue?

How to resolve AdBlock issue?