Charles Darwin ate devilled kidneys washed down with a pint of gin before belching in front of a horrified Queen Victoria. He flew the scene in a hansom cab, pursued by the vengeful monarch and made his way to the Tower of London. Once there he revealed his devilish trap. He was, in fact, a revolutionary socialist and subdued the Queen with an amazonian blowpipe from the Tower’s displays.

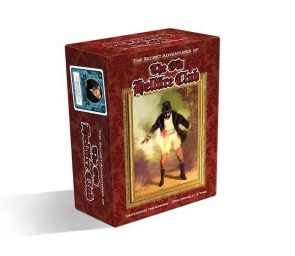

Ah, I fear my throat is a tad dry for me to continue this tale. And my glass, sir, is empty. Really? Most kind, most kind. Let’s see now. Well if you’d like to hear more, let me induct you into The Old Hellfire Club.

All these tales, sir, all of them and more can be woven with a mere deck of cards. And with them, a passport to as much gin as you can stomach! We members of The Old Hellfire Club are fallen on hard times. Now we spend our days frequenting the back-alleys of London town, selling the tales of our grand adventures in exchange for a few pence to spend on drink. But beware: the grander the boast you try to make, the more likely one of your number will slyly undercut you with the truth.

We took our first adventure with The Old Hellfire Club one rainy afternoon. All we had were a hand of Boast cards per player, each marked with a suite such as “Motive” or “Teatime”, a rank from one to ten and a specific item. They’re all keyed to the stereotypical Victorian setting, such as the five of Crime which is “Being An Inccorigible Rogue”. We rolled on the story table to get a subject for our story and got “Why we ended up in Newgate Prison with so much Custard.”

And so our tale began. With storytelling games, it’s often difficult to know where to begin or, indeed, where you’re trying to go. But The Old Hellfire Club is as Victorian, as British and as inherently silly as a jellied eel. The cards hang together like a neat plate of cucumber sandwiches. They just work, each piece of the story falling into place as the last is put down, minds and mouths working overtime to fill in the gaps.

We’re penniless vagrants in Billingsgate Fish Market. Then we’re murdering missionary David Livingstone with a cut-throat razor. After each segment of the story, the player gets to keep the cards they’ve played. But wait! That’s a high card, a nine, and a dangerous boast. It just so happens one of the other players has a lower card in a matching suit, a Penny Farthing bicycle. They interrupt, play the card and get a penny for their efforts. The boastful player, crestfallen, gets nothing, the cards they played so far discarded. The next player in line takes up the tale.

As well as the Boast cards, there are Patron cards. These let you do things like force other players to give you cards, or discard ones they’ve just played. None of them is overpowered and they throw some nice ruts in the smooth path of our hansom cab. There are also Benefactor cards which are supposed to give you bonus pennies for having played the highest card in a given suite. In practice, these fast become too hard to track and we ignore them. We’re too wrapped up in trying to finish the story to bother with such niceties.

And in the end, it doesn’t matter. As the card deck dwindles we’re too wrapped up in trying to bring the threads of the story together to care who wins. As the curtains close on our heroes, surfing down The Strand on a wave of custard, we all sit back, exhilarated, and no-one even mentions counting cards and pennies to determine a victor.

It’s the same with the other traditional game elements of The Old Hellfire Club. A cunning group could try counting cards, to guess how likely a given Boast is to be undercut before playing it. We made that impossible by shuffling in all the extra cards, duplicate values with different names, to get the most variety. They might save their Patron cards for the most dastardly effect, whereas ours lay forgotten, face-down. The story is all.

Afterwards, we can’t help but compare this to one of our all-time family favourites, Once Upon A Time. In theory, there’s more of a tactical structure in The Old Hellfire Club, but you don’t play games like this for tactical structure. The specificity of the cards makes it much easier to key a story together. In Once Upon A Time, with its vague fairytale motif, it’s common for us to keep unspooling an ever more nonsensical yarn, groping for some way to hook it into one of the cards we’re holding: not so here.

In fact, our youngest player who’s often recalcitrant and lost for words in Once Upon A Time wants to play again. So we do. And again, and again, the hysterics rising and falling like waves. We sail up the Thames in the HMS Warrior before demolishing Lambeth workhouse with a broadside of hot buttered scones. We blackmail cookery writer Mrs Beeton for lacing her potted crab with opium. We breaking up an anarchist riot with the Duke of Cambridge’s Own 17th Lancers while Karl Marx gets away with the finest top hat in Christendom.

Yet with each spin around the deck, the stories sound more and more similar each time. We face the same perils, meet the same characters, are charged with obtaining the same items for their favours. What the strong naming of the cards gains in ease of storytelling, it loses in flexibility. We try adding in more or less of the extra cards but in most cases where there’s a duplicate value, there’s a clear keeper. Emily Bronte as the 4 of People is much easier to work with than Yoshio Markino. No, we didn’t know who he was, either.

What too many game players fail to realise, though, is that imagination trumps logic. Every time. Despite facing the same ten cards in each suite, where your stories start and end, how those cards weave together, stay fresh on every play. That’s why The Old Hellfire Club is going to hit the table in front of some dry exercise in Renaissance trade every single time. That’s why The Old Hellfire Club will still be hitting the table with new stories to remember long after those games have been exhausted and forgotten. Huzzah!

You can currently buy The Old Hellfire Club direct from the publishers.

Games

Games How to resolve AdBlock issue?

How to resolve AdBlock issue?