An unexpected but inspired do-over.

Under normal circumstances, I probably would not be reviewing Foxtrot/Renegade Game Studio’s latest, a reissue of the five year old Euro-style family game World’s Fair 1893, which is being released exclusively (and inexplicably) through Amazon. Designed by J. Alex Kevern, this game was nominated for a couple of awards back when it was released but it is very much one of those kinds of games that I play and think “this was ten years too late”. Which is to say that it feels like the kind of game that could have been a bigger hit with wider uptake in a pre-Kickstarter market. But there’s a reason I think this otherwise good but not particularly noteworthy game deserves a full review today. Stay tuned.

It’s certainly a decent, mildly appealing game with a good setting for this kind of fare. It suffers from that “who am I and what am I doing” problem that a lot of designs that toe the line between specificity and abstraction have in that you are just a nebulous “player” rather than an in-game ego or driving force. As the player, you are tasked with sending supporters out to the various areas of the 1893 World’s Fair (surprised?) and achieving majority control in the fields of Agriculture, Manufacturing, Fine Arts, Transportation, and Electricity. It’s a compact design- on your turn you place a supporter into one of the areas and if you have any Influential Figure cards you’ve acquired previously, you can play them to take a special action- typically placing additional supporters or moving those on the board. Then, you collect all of the Exhibit and/or supporter cards in the area you’ve placed and add three new cards going around the board to create new incentives for playing into other areas.

The whole thing is designed around a Ferris Wheel, and when you collect Midway cards you move a timer token along the ride. When it makes its full circuit, the game enters a scoring phase. There is a points award for having Midway tickets as well as the most of them. Then, each of the fair’s fields are assessed for majority scoring and the player who has the most supporters in each gets to “approve” Exhibits from the cards they’ve collected. The final scoring includes a somewhat Knizian method of assigning bonuses for having one of each exhibit class or sets of 2-4 uniques.

This is 45 minute game, quite accessible and sort of mildly appealing in the way that mid-tier family games can be. It’s that game you play and think “huh, that was cute” but you aren’t particularly satisfied or compelled by it. As someone who has been playing this exact kind of game for going on 25 years, there’s really nothing remarkable about this game. Sure, I’ll play it and enjoy it. But would I make it a point to play at the next game event or would my family excitedly gather around it? I doubt it.

Now, the reason I’m presenting this game to you today really doesn’t have anything to do with all of the above. Look, it’s a decent little game, OK. It’s just a dime a dozen kind of thing, and there are at least ten games I could list off the top of my head that I’d reach for over it. But there is one really unique and very timely thing about this specific re-release that deserves praise.

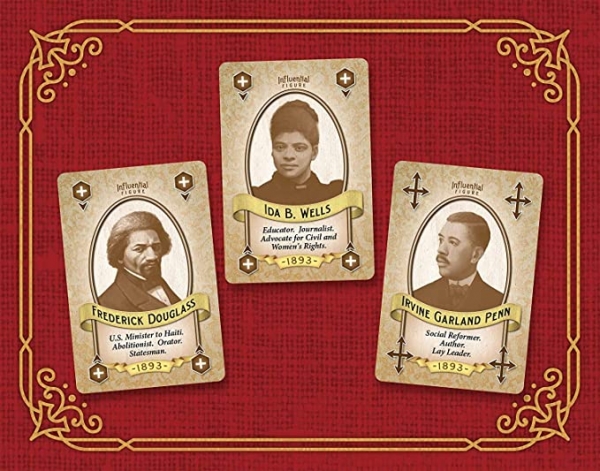

You see, despite the relative abstraction, this is a game with a historical setting as the title unsurprisingly suggests. And 1893 was certainly not the most enlightened time, despite the aspiration of progress that the World’s Fair is supposed to represent. Black Americans were marginalized from wholly participating in the fair, as were women and indigenous people and what was on exhibit could hardly be said to represent anything other than the work of white men. Working with African-American historical consultant Jade Rogers, Renegade and Mr. Kevern have taken this opportunity to go back to this design and revise it, creating a new perspective on the historical event that includes Black Americans and women- there are five new playable historical figures in the game, available as Influential Figures.

There’s celebrated abolitionist, Frederick Douglass, who was at the fair and spoke as the US Minister to Haiti- which was also the only Black nation represented. There’s Ida B. Wells, an advocate for civil and women’s rights who was part of the founding of the NAACP- she boycotted the fair’s segregationist policies of keeping African American exhibits away from the white ones. You’ve got Fannie Barrier Williams, who was petitioned to be on the fair’s Board of Lady Managers but was instead tasked with installing exhibits. There’s Irvine Garland Penn, a journalist, educator, and clergyman who protested the fair’s lack of African-American representation. And Susan B. Anthony, that storied champion of suffrage and progressive change, is also present to lend her influence in making this game more diverse and representative.

The result of just these five figures appearing in the game now is that these folks – who were either historically present or could have been – are now representing a much fuller, more diverse picture of the historical reality. It draws attention to the fact that there were social issues prohibiting the achievement and leadership of Black Americans, women, and other marginalized groups despite the electric lights and dazzling sights of the event. It reminds us that racism, sexism, and white supremacy were the established norm of the time, and that there were social and cultural barriers in place restricting access, expression, and participation.

More importantly, it shifts the setting of World’s Fair 1893 away from the usual blissful ignorance of white privilege that the Eurogame genre all too often typifies. It puts Black faces into the game, and it tells non-white players “you can be here too”. But as the excellently written “Historical Note on Race at the 1893 World’s Fair” points out, that presence was in defiance of adversity and against the will of the prevailing white supremacism of the time. I especially appreciate that the choice of figures includes folks who were actively protesting and speaking out against the segregation that the fair, at the time a signifier of progress and innovation, was regressively perpetuating.

Granted, it’s not a huge addition to the game and it’s disappointing that it’s an Amazon-exclusive upgrade. But this is a step in the right direction for how games with a historical setting can at least in a small way address, confront, and correct outdated white supremacist perspectives and strive toward diversity and more complete representation. It’s also important that Renegade/Foxtrot went about this by engaging with an African-American historian to help ensure a respectful and accurate update. They also published a series of blogs about each of these personalities, a nice supporting touch.

World’s Fair 1893 is a fine game, there’s certainly much worse out there but there aren’t many games, especially with historical subject matter, where the designer and publisher have come back and made an effort to address these kinds of issues. And for that effort, these folks should be praised and supported.

Games

Games How to resolve AdBlock issue?

How to resolve AdBlock issue?