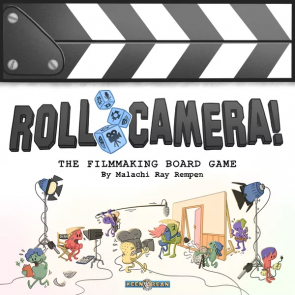

A cooperative effort to create the best film before money or time runs out, Roll, Camera! is an example of great design.

I am not, by and large, a cooperative game player. With precious few exceptions, among them Spirit Island and Tiny Epic Defenders, I don't find the co-op experience to be one that really engenders a sense of satisfaction at the gaming table. In contrast, I am all about games about the film industry because I spend a lot of time writing about said industry (and TV) and anything connected to it will usually have some level of appeal. So, when Keen Bean Studio owner, Malachi Ray Rempen, contacted TWBG about finding someone to do a review of Roll, Camera!, I was perhaps the perfect and perfectly wrong person to take it up; perfect for the latter perspective, not so for the former. But the latter perspective won out and he sent me a copy to dig through and see if I could find a new angle for the script, a new shot for the story, a new edit that might bring the game into a wider focus (Let's say 20mm?)

From the outset, the game takes steps to try to avoid the common pitfalls of co-op games: "quarterbacking" (where one player directs everyone else) and feeling like you're solving a puzzle. The latter is my most prominent complaint, because in many co-ops you can often find yourself in a situation where, after a couple plays, you feel like you've solved that puzzle and further plays lead you to just trying to enact specific circumstances (Hanging out in the Magic Shoppe in Arkham Horror to find an Elder Sign, etc.) to create the most obvious pathway to victory. In our games of Roll, Camera! that path to victory was usually so varied that there wasn't a clear-cut approach or even one that felt more certain than others. In the course of playing at all of the obvious player counts (2, 3, and 4-player and even a solo game, which is another one of my gaming pet peeves), there was enough variety in the Problem cards (challenges to be overcome), Idea cards (assists that players have to keep hidden until used), Script cards (bonus Quality points that lead to victory), dice rolls(!), and the various roles of the players that we couldn't really nail down anything that felt "required" in order to win the game or even an obvious path to take.

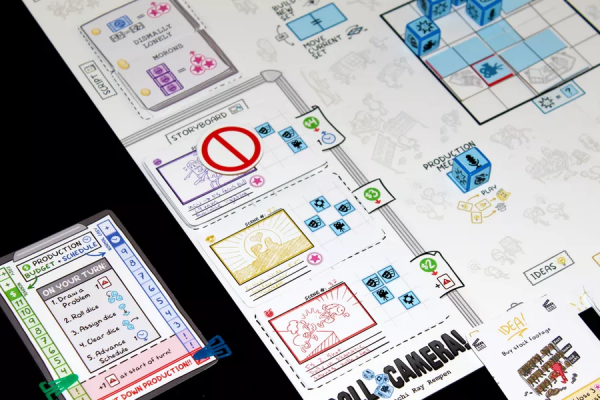

In brief, each player takes a role (Cinematographer, Director, The Star, etc.) and the game follows a sequence wherein a Problem card is played on each player turn, presenting a new issue to solve, the Crew dice are rolled, said dice are placed on the main board and/or on player boards to activate abilities and finish tasks (building sets, shooting Scenes, solving Problems, etc.) Then the dice are cleared (except those frozen for the next turn(s)), the Schedule is advanced (e.g. you lose a day from your total; if you run out of either Schedule or Budget, you instantly lose), and the next player steps up. It's a very easy to remember and simple sequence which leaves all of the meat of the turn in the decision-making process of placing dice and deciding on priorities, rather than performing maintenance tasks. You run through this sequence until you've shot five Scenes. If your movie is better than mediocre (or So Bad It's Good), you win. If not, you've failed and might never work in this town again. Given the nature of filmmaking, one might think that a Director is an absolute requirement to making progress (Certain folks at DC Comics would seem to disagree...) but that's not what we found. Where the Director's Compromise ability (Exchange any one resource (Budget, Schedule, Quality) for another) can be the ultimate backstop and their Reframe ability (Discard any one Scene card in the Storyboard to draw/reveal another) can free up what seems like a dead end between the Script and the Storyboard which dooms you to failure, those don't regularly turn out to be that much more valuable than, say, the Producer's Delegate (change any number of unassigned dice to faces of your choice) or the Editor's Playback (take any used Idea card from the discard and use it again.) Both of those are great backstops, as well, and can feel needed when that role is absent but, again, not so much that it feels like any one role is required, which is a good sign for replayability.

There is pressure that's applied by both the Problem cards on a turn-by-turn basis and the Schedule (time) and Budget (money) dials on an overall basis, so each player's turn is important in the grand scheme. You want to be efficient with your choices and, as noted, the choices of tasks to undertake and dice to spend are the crux of the game's action, so every action taken can be crucial. I haven't yet found an instance like in games such as Sentinels of the Multiverse where my turn is just a holding pattern for the other players, who were going to be the ones who really completed our mission. In every game of RC that we've played, it felt like everyone was contributing directly to our goal, which gave us a real "team effort" sensation. I think the Idea mechanism encourages this, since it asks everyone to contribute a card from their hand and then discuss what would be the best to play. This is an ideal scenario for that "quarterbacking" issue, but it's hard for the quarterback to argue against an Idea that's simply better for the circumstances at hand. If someone else has it, then it's their Idea that will be played, with the next-best (or two) being held in the To-Do List section of the board to be played later, and another simply discarded. That way, it also becomes a group effort at times of one player simply "taking one for the team" by tossing in the least valuable card from their hand to be jettisoned while better Ideas (at that moment, anyway) are put into motion or held for later, which is about the best representation of an actual production meeting as you're likely to see, minus the profane rants and the alcohol (which you can still have in this game, if you're really into that.) The scaling seemed to work well in that respect, too, in that there are more frequent Problem cards coming out with more players and you lose Schedule more rapidly, but there are also many more actions to be undertaken by more players which, in our experience, more than made up for the greater hurdles created. In fact, there's some room to argue that a higher player count serves the design better than solo or 2-player play.

The systems are all quite interwoven, as well, which is the sign of a smart design. The new Problems that crop up every day are a method by which dice become a more precious resource, since you need two of any face to knock out a problem that just showed up today, but two matching dice to resolve one that appeared in the last turn and triples to resolve one that was left from two or more turns ago. So you'd like to resolve Problems on the regular in order to protect not only the number of dice you have available but the type, as well. But the mini-goal inherent to that whole process is that, once you've resolved five Problems, you get to add another point of Budget or Schedule, so there's another aspect of that process to work toward, which can be crucial to your success. Three of our wins at 2-player and 3-player came about with only 1 day or $1 left on our tracking dials (one of them with both!) and we'd resolved our fifth Problem not long before that, so it was a direct contributor to keeping our production running. The one game that we lost at 2-player happened with four of our five needed scenes complete, so the vast majority of games that we've played have been tight affairs. There's a difficulty rating suggested on the back of the dials with a scale from Easy to Easy-Normal to Normal-Difficult to Difficult, as well, so you can always adjust to what's comfortable for your group, which is another sign of a well-tested design overall.

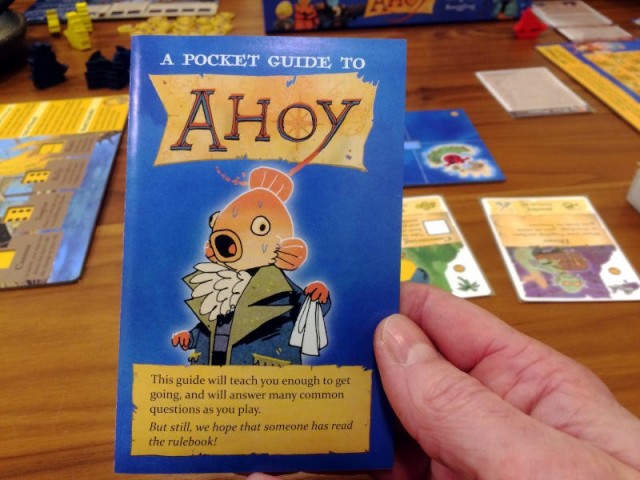

But beyond the smooth implementation of the process and the real feeling of film creation that the game implies (it certainly helps that Malachi, the designer, was (and is) in the film world before he got into cardboard), the best thing about the game is that it's just fun and it emphasizes that approach within that design. With the main box resembling a film slate (the thing you clap together to mark a scene) and the inner box for all the cards and dice made in the shape of a film canister, the theme basically drips from everything. All of the characters and roles are represented by Malachi's "bean people" which came from a comic that he created in his spare time a few years back (hence the name "Keen Bean Studio") and the wry sense of humor and fun is present on and in everything. Each role comes with a Player Privilege (Director: You may loudly shout "Action" whenever a Scene is shot. The Star: You may request a hushed silence from the other players at any time.) The Problems all present a scenario for their challenges. For example, the card that stipulates that at the end of each turn you have to move 1 Set Piece to a far corner of the Set area on the board (often ruining the dice you've frozen for the next turn in order to shoot a Scene) explains that you're doing that because "Your studio space was double-booked and you have to share it with a kids' karate tournament!" Similarly, the Idea cards are also given a story setting. The one that lets you re-roll and reassign up to 3 dice tells you that you can do that because you had an idea to bring in a night crew of film students to work for free(!) That sense of fun permeates the visual design, as well, even beyond the presence of the emotive bean people, as the Script cards that give you more points of Quality (your VPs) for shooting a particular kind of Scene are all represented by colored happy/sad/angry faces to represent your different types of scenes (comedy/drama/action and so on.) On top of that, the game comes with a well-formatted rulebook that makes the game extremely easy to learn and teach, which is an increasingly rare thing these days.

It's just a really fun design from the visuals on up which is, of course, what all games should be, since that's the whole point (having fun) inherent to their very existence. I will admit that I came into this without tremendously high expectations, having never heard of Malachi's studio and not knowing what to expect from a second-time designer (he's done one other small card game, also with the bean people), on top of the personal hesitations noted before (co-op game, etc.) But I was surprised at how professional everything was, from mechanisms to visual design, and found it to be a really positive experience through each play, beginning to end. I think there's enough depth and replayability in the number of Problem, Script, and Idea cards already offered, but when combined with the difficulty settings and the Production Studio cards included in the base game that add even more complications to an already challenging system (such as: Pot O' Gold Studios that requires the Scene order to follow the color spectrum (red-yellow-green-blue-purple), regardless of what the Script says), I think there's enough here to hold your interest through many plays. That said, Keen Bean already has two small expansions available, which are designed to fit inside the film canister in the main box which, again, just speaks of smart design from the very beginning. I talk up Gamelyn's Tiny Epic series for precisely these kinds of things all the time, so I'd be remiss if I didn't point out similar approaches here. As you can probably tell, the word that kept coming back to me, from initial learning to repeated plays, is "smart." I won't say it's a "Cinematic Masterpiece", but it's definitely a "Critical Darling" (second place on the victory track) from this normally harsh critic.

Games

Games How to resolve AdBlock issue?

How to resolve AdBlock issue?