Hanging on the wall in a cramped hallway is a huge painting. Three boats speed across it, their tall sails blurring as they whip in the wind. The rippling sea and bruised sky are patchworks of colour, contrasting fiercely like the elemental enemies they are. Light, catching on the surface, reveals unexpected textures. Rakes of painterly brush strokes shimmer, their refraction bringing it all to life as I move my head.

There are three boats, but it's a lonely, raw scene. Three slivers of humanity sandwiched between the boundless deep and the endless sky. It's awe-inspiring. My bored eight-year-old pulls at my trousers, breaking its spell, and I turn away. The artist is nearby, chatting with some other visitors. I want to say something, but I'm not sure what, and it seems rude to interrupt.

We're on an art trail, a local event where amateur and professional artists alike open up their homes to show their work. We have seen cunning lino collages of nearby cityscapes, soft paintings that express the quiet grandeur of church interiors, awful sculptures. That angry sea with its lonely boats caps the lot. Each one, good or bad, has left me with a nagging sense of inadequacy. There are scenes and emotions that words can't capture.

That morning I had been reading Geoff Englestein's GameTek book. It's a series of articles about the application of maths and science to game design. Much of it is interesting and engaging, but what sets me on fire is the transposition of those ideas. It's one thing to learn what a Penrose tiling is. It's another to make the leap to see that it's a valid game design concept.

Re-framing ideas like this does not come easily to me. It's a lack of imagination, and it's frustrating. Looking at the art, reading Geoff's essays builds that frustration like a coiling spring.

The final straw comes in an office presentation by a "motivational" speaker. It's awful, vacuous nonsense that a moment's critical thought will blow away like sea foam whipping in the wind. He makes a parallel between office teamwork and the Greek phalanx, where every warrior protected his neighbour with their shield. He's an idiot, but it's another useful transposition of ideas. If he can do it, surely, so can I.

Games are the only medium I can claim to understand, so it's games I go to. At home, I open the laptop, gather pencil and paper, sit staring into the garden while emptiness squats in my head like a lead brick. I take a shower, guaranteed to stimulate the mind while you have nothing to write your ideas down, but all I get for my effort is cleaner. The fizzing frustration begins to seep out as poison.

That night is hot. I cannot sleep.

Next day I am reduced to looking at shallow self-help sites on being more creative. The thoughts are like the sea: mercurial and shiny to look at, empty once you break their sparkling surface. It makes me remember, though, that there are actual games that can inspire. I'm pretty sure I could write a whole book of short stories based on my plays of the wonderful Once Upon A Time. The weak scaffold of simple rules and a few cards is a great starting point for climbing much more lofty peaks.

Enlisting my kids to help, we play Story Cubes for a while. We have a great time and it's a fine distraction. But when it's done, the impotence falls back in on me like a breaking wave. Cards and dice are all very well but they build narrative, not mechanics. Perhaps it's time to admit defeat and steal a starting point.

Back in GameTek is a description of a point of Greek law called Antidosis. It translates as "an exchange" and it literally was: the two applicants swapped all their estates and belongings in a dispute over wealth. With that swooping, magpie insight, Geoff spots the potential of this as a novel game mechanic. So that's what I'm going to borrow. To see if I can see further by standing on the shoulders of a giant.

The theme comes first: if it's a Greek law, then it's got to be a game about Greek law. Let's imagine: everyone gets hidden resources and a series of undesirable duties which demand they expend them. That's your random starting point. Then have players trying to trade duties in the hope of getting one they can more easily afford. Antidosis is the only defence, but do you take the risk? Great: but this is a crapshoot. We need some public clues on which to build a strategy.

And this is where the feeble edifice come crashing down. Everything up until that point is easy, a simple shoe-horning of history into a game. Everything after seems impossible. Giving away clues deflates the tension of making the exchange. It's late and there's no way and no one on which I can vent my failure.

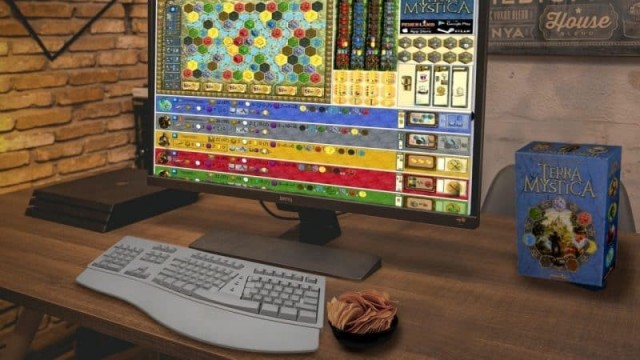

So instead, I sit down and write about it. The words come pouring out, fingers flying over the keyboard, metaphors forming and dumping down on screen. It's not much, but it's all I have. Sometimes, you have to admit there are people cleverer than you in the world. I paste it up, add an image, and save a publish date.

The night is hot. But I rest better, disturbed only by dreams of a perfect, storm-tossed sea.

With thanks to Kathryn Scaldwell for her kind permission to reproduce her artwork.

Games

Games How to resolve AdBlock issue?

How to resolve AdBlock issue?