It's one of the most viscerally evocative monsters in gaming...and it is also a mental anchor.

If you're familiar with the Dungeons & Dragons bestiary, then you probably already have a mental image of the mind flayer: a lanky, perhaps slightly rubbery humanoid with a bulbous head, hateful eyes, and a half face that terminates in tentacles, draped in dark robes reminiscent of those reserved for ill-intentioned high priests. If you are like me, your mental image is probably also in black and white, simply because your first exposure to the creature was a black and white drawing by David C. Sutherland III in the 1977 AD&D Monster Manual. It's such a wicked creature. So very cool. So tacitly Lovecraftian.

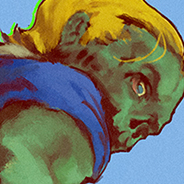

The other day, I came across an artist's interpretation of a mind flayer I hadn't seen before. I was struck by how innovative it was: the creature was muscular and fit, it wielded a heavy sword, its robes were frayed and barbed, and it had a visible mouth. Moreover, the creature's mouth was not merely framed by tentacles, it actually extended into them, giving it a jagged and star-like appearance. It was so interesting, so different...

... and so not.

Don't get me wrong, it was still an iconic mind flayer, unmistakable as such and in full conformity with the Sutherland archetype. The deviations, intriguing as they were, were at the margin, in the details. They always are.

Why is that? I think it lies in our anchors.

Most of us tend to employ a mental heuristic called anchoring and adjustment when we make an assessment about an unknown quantity: we base our assessment on an initial reference point (the anchor) and our appraisal of the difference between the unknown quantity and that reference point (the adjustment). For example, if you want to estimate the time it will take to play a game that you've never played before, you'll likely anchor on the time it took you to play a similar game and then adjust that time upward or downward based on how much more or less complicated you believe the new game to be. The anchoring bias arises because we tend to overweight our initial piece of information when we make judgments. In cases of anchoring and adjustment, we typically fail to adequately adjust away from our anchors.

My conjecture is that there is a similar bias at work with all the nasties in our gaming bestiaries. Certainly, there are well-established archetypes and recognized phenotypes, and no one wants to be labeled as the person who "ruined the mind flayer" or "butchered the owlbear." But there is some anchoring going on as well, rooted, I suspect, in our "show and tell" approach to exposition. It goes like this: I want to publish a book/RPG/card game/etc. with a bunch of cool monsters in it, and I want to make it slick and pretty and worth your money, so I include some gorgeous art illustrating all the nasties to get you excited about the product. In doing so, I've encumbered you with not one, but two anchors: one visual, one conceptual. With each illustration, I've locked an image in your mind that inherently limits your ability to imagine a creature other than as I've depicted, despite any written description, no matter how inspired; with each written description, I've locked in your mind a creature's essential characteristics so that you are hard pressed to refine, let alone redefine, its capabilities based on any visual representation, no matter how imaginative. These are powerful anchors that limit our creativity to variations at the margin: it seems okay to give a mind flayer a fighter's physique, for example, but the tentacles are sacrosanct.

For my part, I've come to prefer "show or tell" over "show and tell" for exposition, especially for games designed to foster imaginative play. Show me the creature and let me make up a description for myself, or give me a description and let me conjure up my own image for the beast. Of course, the "or" is harder than the "and." It requires active engagement by the player. It requires an investment of time and mental energy. It also means that it may take longer to play the game and longer to appreciate it, something that some modern gamers won't tolerate. But you know what else it does? It obviates ever having to hear, "What the - that's not a mind flayer!"

Oh, really?

Let me ask you this: If you didn't already have that iconic image of a mind flayer in your head and just read a description of its intellect, intent, and abilities, what physical form would you have given it? And if you only saw an image of the thing, what abilities and intent would you ascribe it?

Games

Games How to resolve AdBlock issue?

How to resolve AdBlock issue?