Does downtime matter or are you missing an opportunity?

[Person on phone at the gaming table]: "Well, we're in the middle of a Western Legends game, but it's not my turn so I'm just sitting here WAITING..."

The topic of downtime (i.e. waiting while someone(s) else takes their turn) is a popular one in modern game design and discourse. Many games are dismissed by potential or one-time players because the idea of having to wait a couple minutes before being directly called on to do something is intolerable. To many players if, like a video game, they're not doing something involving the game with every second of their time (and, too often, precious little of their actual attention), then the game itself is flawed and not suitable for regular play, if at all. This has always struck me as the most foreign of concepts for a variety of reasons, the most prominent of which is that gaming is a social activity for me, but also because so-called "downtime" is often a good moment to actually consider one's strategy, which may be the better measure of whether a game is worthy of attention or not.

First off, let's get one thing clear: Downtime is not analysis paralysis. We all know someone afflicted with the AP problem; where one player considers and reconsiders their next move for an extended period while everyone else at the table sighs in frustration. That situation is a whole different discussion about who is fun to play with and who isn't. What I'm talking about is the normal span of time between one player taking actions and the next time, created by other people doing the same in a normal fashion. This can be affected by a variety of things: the number of players involved, the inherent pace of the game, the amount of space between players and their immediate environment in the design, and so forth. A good example of the latter trait is Runebound. Many people have complained over the years about the downtime in adventure games like Runebound, where turns can occasionally be lengthy and if you're playing with four or more people, you can wait some time before you get the chance to swing a sword with your character, as so many are busy swinging with theirs. The fact that you can be adventuring in locations across a continent from each other, often with no immediate impact on the fortunes of others in the game, only exacerbates this.

In contrast, two-player abstracts, like chess, normally do not suffer from this, since the only person to pay attention to is the one across from you and every move they make will usually have immediate impact on your prospects for victory, however large or small. In fact, most two-player games aren't often accused of being problematic with downtime because of the more narrow confines of the competition. But a key element of two-player games is the fact that you're playing a game with someone else. To me, that element does not shift when adding more people. Gaming for me is a social endeavor. I'm with this group of people, playing this game, because I enjoy their company and am interested in doing this activity with them. Consequently, their turns are almost as interesting as mine are. I'm interested in what they're doing and how they're doing it and also in the story that the game is telling about this time that we're spending together. I don't ever want to leave a gaming table shrugging my shoulders at something forgettable or not feeling like I had a good time with these people that I enjoy being around. To me, staying involved in what's happening on the table is part of that, in addition to being able to tell a story about that Tyrants of the Underdark game where I managed to play two Intellect Devourers in the same turn and wreck the hands of my opponents on the last round while I kept hold of Auramcyros for the win.

Just as importantly for those of us who like to win said games, it's often crucial to be aware of just what your opponents are doing. I saw a review of Pax Pamir, 2nd Edition on BGG the other day that listed the game's downtime as "Medium." Newsflash: There is no downtime in Pax Pamir! If you think there is because it's not you who is paying coins or moving cylinders, then you're likely going to lose every session of the game that you play. Paying attention to what others are doing in games like that is absolutely essential to playing well. If you don't observe your opponents' strategy and shape yours to meet, evade, or defeat it, then you're doing yourself a disservice, as they'll probably be running rings around you by the time it's over (or just having four more points than you in a Dominance check, which means the game is definitely over.). To me, this same principle still applies to games like Runebound, as I'm usually eager to see just what treasures my opponents turn up in the towns they visit or how successful they are in dealing with the creatures out in the world that I may have the chance to take down if they don't defeat them.

Furthermore, no matter how exciting the next five minutes on Twitter might seem, so-called downtime is also the best time to consider one's strategy or assess how the game is shaping up. From my perspective, the amount of time that I'm considering the next turn's move is usually a good measure of whether the game is worth playing in the first place. The Hacan have just jumped through the wormhole to take control of Hope's End, spoiling the move I'd planned for my Arborec two turns from now. But it's now the Mentak player's turn. Should I pay attention or not? Using the opportunity given by other people taking their turns may be a facet of the design to begin with and it usually means it's a factor of depth that the designer intended. People usually draw this line when deciding whether games are "heavy" or "light", but even light games like For Sale! can take some thinking if you're trying to guess how your opponents will play their cards in the more rapid selling phase. There's no downtime there. I'm watching people play cards the same way I would be if I was in a poker hand.

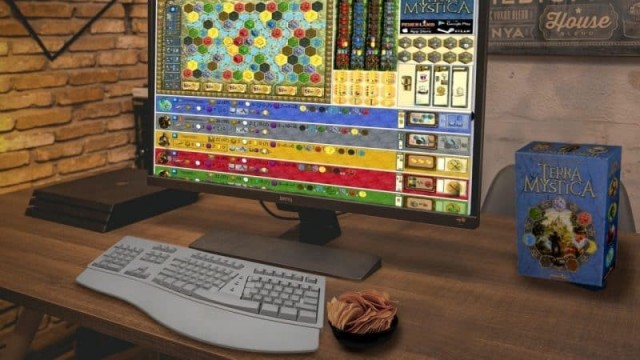

But modern design has incorporated this perception, whether because of new innovation or simply the exaggerated concern over presumed downtime. In some cases, it's a sign of developmental trends or a new way of approaching a mechanic. Dudes-on-a-map games can often be accused of having downtime, as players build armies and marshal their forces. One way that Tiny Epic Kingdoms short circuits this idea is by using joint actions. One person takes an action and everyone has the choice to either duplicate that action or gain resources. So there is a decision to make based wholly on the game state on every player's turn. Rising Sun does something similar with its mandate and kami phases, where everyone is involved and the board usually has to be consulted repeatedly to determine the outcome. Another method is simultaneous action, like in The Quacks of Quedlinburg, where everyone acts together and variation (and playing skill) is determined by how far people are willing to push their luck with their cauldrons. Probably the most notable overall design change is in the push away from "I go-You go", where players make multiple moves and do everything they can do in their turn, to an action-based system where players take one action of many before play passes to the next player. A notable exception to this in the modern era is Star Trek: Ascendancy, where players do, in fact, build, move, explore, and fight, exhausting all resources and actions, before another player can do anything. It's so odd in modern design trends that it makes everyone hesitate in the first couple rounds every time we play.

But the fact remains that the game still works for two reasons: 1. The fluidity of its play, where turns are fairly direct and there shouldn't be a ton of hemming and hawing before making a move. And 2. Because it's still really important for people to pay attention. Part of that fluidity means that the game situation can change so rapidly that if you don't continue to watch what your opponents are doing, you'll miss a lot of opportunities to forestall or resist it. Far better to realize that an opponent just set up a direct path to your homeworld before it comes around to your turn and you have to alter your plans in a hurry. That, again, is the essence of playing games with other people, rather than just waiting for them to be done so that you can do something. It's like the difference between actually listening to other people and just waiting for them to be done talking so that you can say something. If the only thing keeping you at that game table with these people is because you get to play a card or roll dice or move a dude, then I may suggest that you take a moment to contemplate why you're there in the first place. I can see that attitude fitting rather seamlessly with the surge in solo board gaming in the last couple years, where many people seem to think that the only impediment to them having fun with a game is... other people. That, if anything, is the polar opposite of my perspective. I can play video games alone all I want. When cardboard hits the table, it needs more than just me hovering over it and that means that I'm there to spend time with those people.

Now, there are games that play slowly. Dune is a great example of one that takes serious consideration and, quite often, much discussion between turns or especially when a shai-halud comes up. But that's all part of the game. If you expected it to be over in 45 minutes, you probably shouldn't have sat down to Dune. Plus, there's nothing that says that games have to be long or slow to make them good games. I'll sit down to something like Lovecraft Letter any day. But I'm also more than happy to play something like Here I Stand, where it could be a whole 10 minutes before I get to move a piece again. But that's 10 whole minutes that I can watch other people perform in this game that I'm enjoying with those people. And that's what makes the difference and why "downtime" isn't even a consideration for me. Even when I'm not touching a piece or drawing a card, I'm still playing.

Games

Games How to resolve AdBlock issue?

How to resolve AdBlock issue?