If you played tabletop games of any stripe in Britain in the 80's, Games Workshop was your entire world. The world-famous retailer of miniature battle games started life in 1975 as a small importer of exotic games. Even if you didn't play any of the classic titles they designed in-house, any hobby material in shops stood a good chance of having come in through GW. My gaming life started out as a slavish acolyte of their products and imports. Yet over the last three decades I've come to hate them and love them again twice over. Most recently I was won over by Silver Tower which I reviewed for SU&SD. Many gamers never came full circle and still regard them as the devil incarnate.

The story of how one of the world's best-known hobby companies came to make so many hobbyists so angry is intimately bound up with my own life. It's a story that's one that never ceases to fascinate me. And now, Games Workshop seems to want those gamers back. The current issue of its magazine, White Dwarf, abounds with new material for the slew of new board games they've published. Those titles have met with critical acclaim and seem astonishing value for the components packed inside.

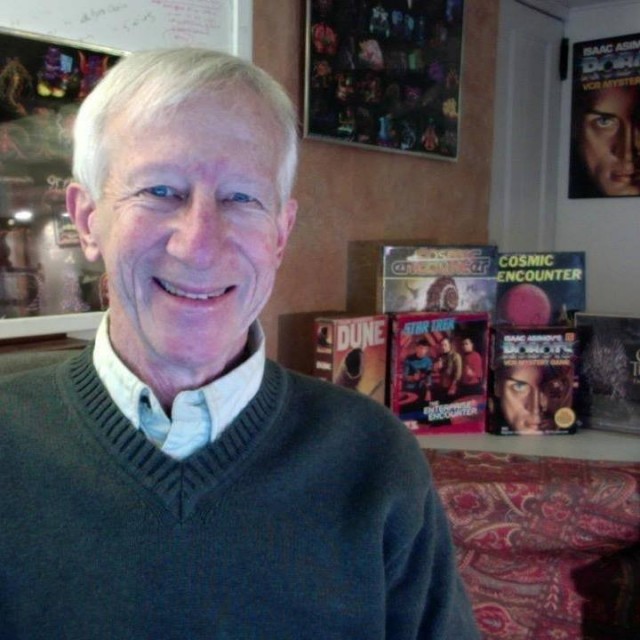

Who better to ride this chimera with than Rick Priestly, co-designer of Warhammer Fantasy Battle, who worked at the company for most of its life? He left the company in 2010 and now writes and designs games for a company called Warlord Games. "It's a kind of sheltered community for ex-GW employees of the 1980’s as far as I can tell," he told me. "As a games designer everything you do gives you the opportunity to review things you’ve done or encountered in the past. It’s a journey." Even after so many years and so many great board games, his favourite is still one of the first: the Judge Dredd board game. "We started out as an importer of games with a small chain of shops," he recalled. "Plus a studio in London that produced White Dwarf and a number of role-playing games and board games like Dr Who, Talisman and Judge Dredd."

From these relatively modest beginnings there was a sudden explosion of board games in the mid 80's. Many of these titles are still well known today: Warrior Knights, Fury of Dracula, Blood Bowl and others. Game boxes which were the bricks in the foundation of my hobby. Almost every day I'd spend school plotting some new strategy for one of them. Then I'd race home with my nerdy friends, pull it off the shelf and play. "Those were all produced in the Nottingham studio around the time Bryan Ansell bought out the original founders," Rick told me. "We wanted to build up the studio to produce a range of home grown product, recruiting games designers and sculptors, and aggressively expanding the business."

Buy-outs followed by aggressive expansion would become a hallmark of GW business practice in later years. Indeed it would sow the seeds of loathing among the company's detractors. Yet at this point, as it would in the future, it yielded a period of immense creativity, the echoes of which are still felt in the hobby today. As a huge Fury of Dracula fan, I felt compelled to ask Rick about its designer, Stephen Hand, who seems to have vanished from the hobby. "He was one of the young, new and very talented games designers that joined the team at that time," he replied. "He didn’t work for us for very long, and we didn’t keep in touch, so I’ve no idea whether he continued to design games or not. A lot of the GW designers from those days went on to work on computer games. so who knows?"

Give all those groundbreaking designs from all those talented designers, it's surprising to find that this explosion of innovative board games was, in fact, a dangerous experiment.m "We didn’t know what was profitable and what wasn’t," Rick revealed. "This was in a pre-digital world in which the levels of business analysis available were pretty primitive. When Bryan took control the assumption was that the RPG’s and board games represented a large part of the income and profit. However this proved to be erroneous. It quickly become obvious that the profit was actually generated by Warhammer and Citadel Miniatures".

One thing that helped to hide this was the success of the fondly-remembered family adventure game HeroQuest. The game design was actually from a mass market publisher, Milton Bradley, but GW provided the miniatures. It sold well enough on both fronts to win several awards and launch a number of expansions. Yet even so, opinion inside GW varied as to its value to the company. "Tom Kirby, the current chairman always plays down the value of HQ," Rick told me. "He points out that the resources put into it would have been more effectively spent on our own lines. John Stallard, sales director at the time, has always said that it was an enormous help in recruiting new gamers and bringing customers into the shops. Take your pick."

The last traditional board game from GW, the lackluster Curse of the Mummy's Tomb came out in 1988. Yet this proved to be the dawn of a new wave of classic hobby titles with a focus on figures over cardboard. "By then I’d say it was obvious the board games were under-performing," Rick explained. "We were starting to realise the potential of the 40K game and everyone was quite excited about exploiting the new setting in various ways. Space Hulk and Dark Future were skirmish wargames that made use of gridded boards, but focused on models. That was where we saw our strengths lying."

During this era the company underwent a sudden transformation. The wide vision on hobby games of all kinds vanished, replaced by as laser-like focus on miniatures. The most obvious change was in White Dwarf. Once full of broad hobby content with lots of role-playing material, it dropped everything not GW related and doubled down on modelling. I was sixteen at the time, addicted to Dungeon and Dragons, and with the force of emotion only teenagers can muster, it felt like a betrayal.

What I didn't, couldn't understand was that there had been another management buyout. Rick was a part of it. "I become Director of Product design," he recalls. "I was responsible for the entire product range, plastic tooling and print buying." He disputes my memory of it being quite so sudden. "We knew we needed to build the core Warhammer offer, but we also continued to plan in board game releases, including a new version of Talisman. It was only the ever-increasing success of the Warhammer and miniatures lines that led us to focus on that to the exclusion of everything else."

As he explains it to me now, an adult to someone pretending to be an adult, it's obvious why this had to happen. "In the last years of Bryan’s ownership the company was run on a shoestring with no investment to expand," Rick told me. "When we did the buyout we had to borrow about 14 million pounds of venture capital," he continued. "That’s quite a lot of pressure with houses and everything you own being on the line! No matter how much you love what you’re doing you have to stay solvent to keep on doing it. And we grew the business organically from a turnover of just over 10M to about 100M in ten years."

An unimportant cost of doing all that extra business was my business. I walked away, spending my late teens and twenties first on role-playing and then Magic: the Gathering. In the meantime, GW went from strength to strength following its strategy of releasing stand-alone games based around miniatures like Battlefleet Gothic and Mordheim. "We wanted to cover different themes within the traditional tabletop wargaming field," Rick revealed. "It also gave us the chance to do create new games explore the Warhammer settings, and invent new ones. As I recall the board game market was really in the doldrums at the time. That's was one of the reasons HeroQuest was so remarkable and why MB valued the relationship with GW."

However, there was still a desire inside the studio to produce more traditional games, even if their profit margins were suspect. "We were keen on providing the sales teams with at least two big box games a year at the time, so we rattled through them," Rick told me. "One was Warhammer Quest which had always been on the cards as a traditional dungeon bash game. By then we were really struggling to sell anything that wasn’t Warhammer, but we couldn’t make enough Warhammer supplements to give the sales team new product every month."

With typical creativity, Rick and his colleagues did what they could to try and turn this issue into a strength. And the answer was more board games. "The problem wasn’t so much the writing and designing of the games," Rick said. "It was making enough new miniatures. So we tried this idea of using some old plastic frames to create quick, cheap board games like Lost Patrol to give the sales teams something to sell. I don’t think they were very successful at the time. I was amused to see the recently re-visited Lost Patrol described by GW as a classic. My memories of it at the time were that that the sales guys complained endlessly about it. All they wanted was more Warhammer really."

So, slowly, the board games dried up. At the same time so did all my local D&D and Magic players. By the time I looked at sixth edition Warhammer Fantasy, GW hadn't published a board game in years. But I was happy to take sixth edition over a closed box game at that point. It was a far more balanced and demanding design than the previous two "herohammer" versions, one that took good thinking both before and during the battle to win. At around the same time GW picked up the licence from the Lord of the Rings films and used it to start a new miniatures game. It was a commercial success, but it actually lead to more doldrums for the board games.

"It had been extremely successful in the early 2000’s," Rick recalled. "But it was perceived as responsible for a collapse in sales rather than celebrated as the hugely successful venture that it was. This was fundamentally down to the nature of the business model together with poor management . Whatever the reason, new games of all kinds were very much off the table by then. It would be a bit like the Ford Motor company suddenly deciding to make a few bicycles." Instead GW decided to make money by selling on the rights to all those classic games from its past. "The licensing department was tasked with generating some income from old intellectual property," Rick said. "Fantasy Flight were ideal because they were set up to operate as that kind of business. And also gamers!"

At this time, Rick was beginning to wind down his involvement in GW, and had increasingly little to do with the management of the company. So he wasn't able to shed a lot of light in to why they suddenly decided, after more than a decade of no board games, to re-issue Space Hulk. "Desperation," was his best guess. However, he was a bit more helpful when it came to explaining the infamous purge of fan material that happened next. ."My impression of the senior management at GW is that it was, and remains, self-reflecting to the extent that it is impervious to negative publicity," he opined. "As to why such an order may be felt to be necessary, to some extent this is a problem that all IP holders face. It is as much a reflection of how the law works as the attitudes of the IP holders themselves."

For all the fury its actions generated among fans, now Games Workshop wants board gamers back. It's already released a slew of board game titles this year both old and new. And there are more in the pipe. Their current communications manager, Andy Smilie, reminded me that Blood Bowl and Titanicus have already been announced and there are more unrevealed designs in the pipe. "2017 is going to have people wishing they had more free time," he quipped. I asked him about some of the games that were released after Rick left, including the surprise re-release of the supposed limited edition Space Hulk, which made GW another wave of enemies from existing owners. "The response to the 2009 edition really was epic," he replied. "It left us feeling like we were doing a great many hobbyists a disservice by not returning to the game. Having said that, we wanted to make sure that we stayed true to our promise that the 2009 set was a limited item. That’s why we approached the fourth edition as new game in its own right adding extra board sections and missions that helped redefine the experience."

That's PR speak, of course. But it also sounds a little deaf to the outrage it caused, which fits in with Rick's comments about GW management. In fact looking back through his narrative it seems that bad management decisions have been something of a hallmark all through the life on the company. One might even go so far as to say that it's been a success in spite of itself. Even when I was planning this feature I struggled to get any input from them at all. They don't have a press or PR department, and they don't seem to welcome emails on the subject. So it seems unlikely things are about to change any time soon. For the sake of all the awesome-looking board games they've got planned, I hope I'm wrong.

Games

Games How to resolve AdBlock issue?

How to resolve AdBlock issue?