My daughter’s 5th edition Dungeons & Dragons group contains all sorts of weird and wonderful characters: a dwarf druid, a demon-blooded rogue, a draconic sorcerer. She cannot understand why my group favours simpler archetypes like humans and elves, warriors and wizards. For her, like a lot of modern players, RPGs are a method to live out their wildest fantasies. So, by way of explanation, I got her playing Old School Essentials.

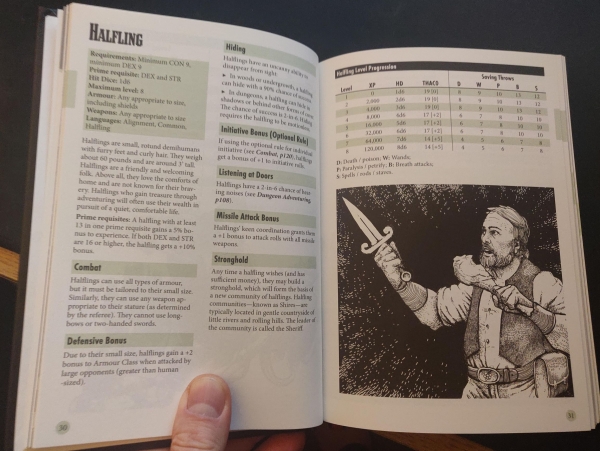

Old School Essentials is a restatement of a much older edition of Dungeons & Dragons known as B/X. That stands for “basic” and “expert” after the two sets that comprised the rules. It’s from a much, much simpler age. There are a mere seven classes including dwarf, elf and halfling: that’s right, a racial identity dictates the mechanics of your character. There are no feats nor skills nor mandatory backstory. You roll three six-sided dice six times to determine six different stats, your class dictates what skills or spells you have, and it’s straight into the dungeon.

One of the great benefits of this is its simplicity. Our little group throws its characters together in about ten minutes. There’s a magic user, a dwarf and a cleric. None of them has a stat above 15 and the poor cleric is stuck with an intelligence of 5. Her player, used to the heroic stylings of the current game, is not happy. Like 5th edition, these translate into dice modifiers for things like attack and defence. Unlike 5th edition, the stats themselves get rolled against on a d20 in place of skills.

When we say it’s a “restatement” of B/X it is *exactly that*. There is nothing new here at all, just the previous text carefully combed and untangled of contradictions and confusions. It is presented in clean, clear pages full of classic art and easy to reference tables. As a dungeon master, it’s a dream come true: fewer rules to juggle, easier to find the ones I do forget.

Thanks to this clarity, Old School Essentials has become a poster child for what’s known as the Old School Renaissance. There are entire essays explaining what this is, but perhaps the best elucidation is simply to look at adventure modules written for the system. Keep on the Borderlands is the go-to starting adventure for B/X. It has almost no narrative arc, opting instead to plonk the players down outside the “Caves of Chaos” and presume they’re happy to venture in. It, like all the old B/X modules, is a hundred per cent compatible with Old School Essentials.

We’re running a module by the author of the cleaned-up rules, Gavin Norman, called The Hole in the Oak. It has a similar premise of presenting the players with the titular hole and assuming they want to delve. Inside, it’s even more stripped down: no flavour text, no dungeon ecosystem, no NPC motivations. Just traps, treasure and lots and lots of monsters.

We won’t go into more detail about what they found in there for fear of spoilers. But at first, the old fashioned character classes dismay them like being caught in a straightjacket. They’re used to a paradigm where almost any class has access to healing if they choose the right option. Here, that poor stupid cleric comes into her own in keeping them alive. But as the quest unfolds, each begins to enjoy the distinct niche they occupy, taking pride in what they do well that the others cannot.

What doesn’t sit so well with them is the mechanics. Simple, as any that’s played a Eurogame will know, does not always equate to accessible. While Old School Essentials has fewer rules, they’re also less cohesive. Sometimes you’re aiming to roll above a target number, sometimes below. Negative armour class and a table lookup to find a to-hit number infuriate them. Thief abilities are checked on a percentile, which is used nowhere else. It’s easy to forget how clumsy this stuff was until you’re reminded of it first hand. The game does have a system to convert to a modern armour class but, as it says, since the default in all the source material is the old-fashioned way there doesn't seem a lot of point in using it. There’s a ton of stuff that isn’t covered at all.

But this is exactly where Old School Essentials earns its Old School Renaissance stripes. A big part of the mindset is about the Dungeon Master making fair calls based on good play instead of rolling dice. As a good example, their party has no Thief, which means no access to find traps. Instead, they’re forced to ask me questions about the dungeon and artifice practical solutions. Any character can find a pit trap if they methodically poke the floor in front of them as they advance. Forgotten equipment like the ten-foot pole or silver weapons become invaluable again.

This aspect of old-school roleplaying, they love. Their group paradigm tilts more toward role-playing than combat and, to my surprise, they embrace the tactical aspect of old-school play. First level characters in Old School Essentials are very fragile, with meagre scraps of hit points and abilities. So instead of rushing headlong into monsters, swords swinging, a more subtle mix of stealth and strategies are required.

Despite their cleric and the caution, however, death becomes inevitable. And here, an unexpected advantage of this genre makes itself clear. The player is back in the game in another ten minutes with a fresh character. Without the need to traipse through pages of backstory and power balancing there’s no particular attachment to a given character, either. It’s a bit like a video game: you die, and you start over until you learn to get it right. If a character survives and grows, personality and backstory become emergent, something to earn and cherish, more easily worked into the campaign narrative.

After the game is finished, I ask them what they think. Everyone had a good time, but there’s no rush to embrace this over the modern form of the game. They found the clunky mechanics offputting. And one of them makes a telling point: there’s nothing to stop a DM from adopting the most fun aspects of old-school play in any system.

On reflection, it’s how I tend to approach 5th edition, by default: there might be a skill check, but I’ll set the difficulty depending on how well you plan or role-play the situation. Nevertheless, for middle-aged me, who is often corrected on the Byzantine 5th edition rules even by neophyte players, I’m not going to abandon the virtues of speed and simplicity quite so easily.

Games

Games How to resolve AdBlock issue?

How to resolve AdBlock issue?