What is a game, what is a puzzle,

how is this important for designers (and for players)?

[This is another of those “on the edge of understanding” discussions.

This is very long compared with the typical articles and comments you see on sites like this. But compared with a book, it's short (6-7% of novel length). This is a fundamental topic in games and game design, and I've found that trying to summarize or briefly explain a sometimes-contentious topic is not sufficient for everyone to understand, so I need to take more space to explain adequately.

But if you try to skim it, you're unlikly to fully understand it.]

Sometimes we use the term “game” to mean “playing at something”. For example, several years ago I made a “game” out of thinking of phrases to represent a college-student friend, and my friend liked to try to guess from the acronym what the phrase was. (For example, “THG”–Tommy Hilfiger Girl, because she often wore that company’s garments.) Was that actually a “game”? No, I think I was making up puzzles, which is a kind of puzzle in itself, and of course it was a puzzle for her, not a game.

I don't like solving puzzles--though I enjoyed making them up for my friend-- because to me, in the end, solving a puzzle is a waste of time. It achieves nothing, and I feel no sense of accomplishment when I solve one. If it's an obstacle in my way, I deal with it and get on about my business, but I don't like it. I'd rather use my time to create something or to socialize, or use my brain to find a solution to a practical problem. Why bother with a puzzle?

Yet puzzles are more popular than games. “Brain-teasers” and cross-word puzzles are in most newspapers, Sudoku is ubiquitous. The venerable Games magazine, founded in 1977, is self-described as "a consumer magazine featuring a wide variety of verbal and visual puzzles, brainteasers, trivia quizzes, and many other features, as well as reviews of new board games and electronic games." It's a lot more about puzzles than games. When I go to a bookstore I see far more books about puzzles than games in the "Games and Puzzles" section.

One reason why single-player video "games" have become so popular through more than 30 years is that they are interactive puzzles, not games--especially the widely popular social networking "games."

There are significant differences between games and puzzles in how you play, and how you design them, and that's why I've undertaken the task of defining the two types of play. Much of the discussion of video games and video game design resolves and revolves around the difference between what I am calling games and “interactive puzzles”, but hardly anyone comes to grips with the fundamental difference.

I’m looking for definitions that make a difference for designers, as well as for players. It only confuses things when we call both single-player video “games” and more-than-two-player family games, "games." Yes, in both there are challenges to overcome. But climbing a mountain is a challenge, though not a game (perhaps more like a puzzle, now that I think about it). We need more than just “challenge”.

In the end, no definition is going to satisfy everyone or every case. But thinking about definitions can help you understand better what you’re doing when you try to design a game--or a puzzle.

First, the Summary

If we had to make one very broad generalization about games and puzzles it would be that games are about people and psychology, and puzzles are about calculation and logic (and, if all else fails, about guessing (trial and error)).

A “puzzle” usually has a goal, some state that you want to reach. Puzzles have a correct answer. Card Solitaire (a puzzle, not a game) has a correct answer--or no answer--for each possible arrangement of the cards, but by shuffling the cards we are able to create a great many slightly different puzzles.

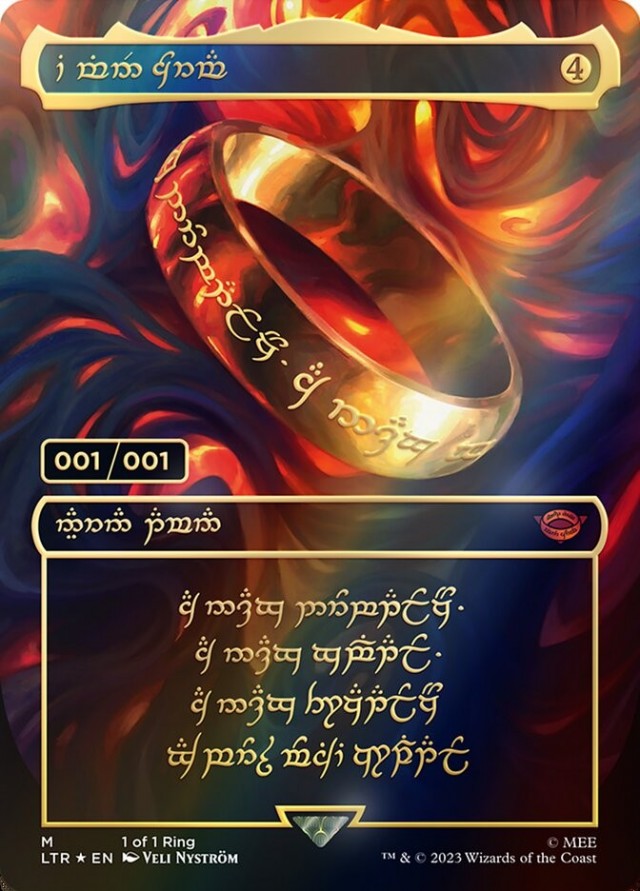

A puzzle can be solved. And once you’ve completely solved it there’s not much point in doing it again. Some puzzles, like a jigsaw puzzle, may be so big and complex that you can’t remember the solution. Where the traditional video game has no chance factors, such as the arcade version of Pac-Man, then you can ultimately solve it just as arcade Pac-Man has been solved. In 1999 someone perceived the patterns (later explained in a Gamasutra article analyzing the programming (http://www.gamasutra.com/view/feature/3938/the_pacman_dossier.php?print=1 ) and played all the way through 255 levels to the end, eating every ghost and never dying, at which point the game crashed. We call the card activity Solitaire a game, but in fact it is a puzzle, by this definition. So we see how some things that we call games are more properly characterized as puzzles.

Moreover, puzzles do not involve conscious intelligent opposition. There is (as yet) no intelligence or consciousness in a computer, although it can do some complex calculations. The key element, in the end, is that puzzles are for one person and games are for at least two persons (or semblance of persons) in opposition. A cooperative game like the popular boardgame Pandemic is essentially solitaire, even though you substitute several players for the solo player. And it is a puzzle, not a game, as there is no semblance of intelligent opposition. It includes several ways to change the strength of opposition, but in the end players solve the game and are much less likely to play thereafter.

Games do not have solutions, right answers, or if there is a solution to the game as there is for chess, it is beyond human capacity to figure it out. Furthermore, you can’t influence the psychology of the “opposition” in a puzzle, and you can in a game. Even in a perfect information, heavily studied and analyzed game like chess, there is a psychological element, as you can fool the other player or break his will to resist even if your position technically does not justify his surrender.

Characteristics

I’ve listed the characteristics of games and puzzles in the table, then I’ll discuss each one in turn. This list is naturally a black-and-white division, though in practice there are many activities that are in the large gray area between game and puzzle, so after the discussion of characteristics I'll try to determine how game and puzzle meet.

|

| Games | Puzzles |

| Choices and Solutions | Multiple choices that can lead to success; Good games do not have dominant strategies or saddle points | Saddle points and dominant strategies are common; frequently “solvable”; pure puzzles always are solvable (one course of action ends in success) |

| “Contests” | “Contests” are not really games. You can time how long it takes someone to do something and declare whoever is fastest the winner, but that’s not a game | “Multi-player solitaire”: everyone works at a puzzle within a contest framework, whoever does best by the “time” limit wins the contest. |

| Failure | If you screw up or fail, you lose. Trial and error (guessing then checking) is not suitable behavior | No danger of “losing”–if you fail you can just try again. Trial and error (guessing then checking) can be used to find the way |

| Opposition | Intelligent opposition | No intelligent opposition: obstacles/challenges rather than active decision-making opponent |

| Origin of challenges | The challenges come largely from other players, within the context established by the designer(s) | The challenges come from the puzzle-maker(s) |

| Yomi | The possibility of “Yomi”, reading the intentions of the opposition; this is much more practical when the player is face-to-face with his opponents, able to read visual, auditory, and other clues | “Yomi” only possible if you can read the intentions of the puzzle creator; very difficult to do because the puzzle creator is not present offering cues to his intention |

| “Completion” | A play of the game may end, but the game can never be “completed”, and you can never “beat the game”. If the game is very good there’s always a reason to play again | Can be completed: there’s no longer any reason to play. You can “beat the game" [puzzle] |

| System vs. psychological | Games have a strong psychological component; players mostly contend with the other players, not with the system | Puzzles have little or no psychological component; player(s) mostly contend with the game system, not with other players |

| Conflict | Games (like stories) usually involve direct conflict amongst the participants | Puzzles lack conflict (though there are obstacles), in considerable part because there’s only one participant |

| Story | May have an explicit story component | May have an explicit story component |

| “Mastery” | A game--unless it is very simple, such as Tic-Tac-Toe or Rock-Paper-Scissors--can never be entirely mastered, it always depends on the quality of opposition | Puzzles can be completed. Those with point scales can be played to improve mastery (high score). |

| Randomness and Uncertainty | A game need not have randomness or uncertainty, though a two player game with neither is probably solvable and is actually a puzzle, for example chess or checkers. | Randomness and uncertainty can be present in something that still conforms to most of our characteristics; there can still be dominant strategies although there are unlikely to be saddle points |

[The characteristics in this table are in the order they came to me; there's likely a more logical order, but I haven't figured it out yet.]

Choices and Solutions.

Games have multiple choices that can lead to success. Good games do not have dominant strategies or saddle points, a single best move that must always be pursued for best success. Saddle points (surefire, always-best moves) and dominant strategies are common in puzzles; the solution to a formal puzzle is often a saddle point. Pure puzzles, ones without uncertainty or random elements, are always solvable (one course of action ends in success, that is, the entire activity has a succession of saddle points). Another way to put this is that pure puzzles are deterministic. In general, if you do the right thing every time, it will always work (and solve the puzzle) every time.

However, at some point the solution to a puzzle becomes so complex that no human can encompass it. Checkers, for example, has been brute-force solved via the computer program Chinook, which has a database of every possible position and the best move for each position. The remarkable human checkers champion, Marion Tinsley, lost only seven competitive games during his very long reign, and defeated Chinook before the final solution was incorporated into the program. Chess will be solved sooner or later, and it has already been proved mathematically that a perfectly played chess game will always and in the same way, although the proof did not indicate whether that was a white win, a draw, or a black win. So while checkers and chess are puzzles according to our definitions, they are so complex that no human can successfully figure out the solution and we can treat them as games.

Theoretically, you can use the mathematical Theory of Games of Strategy to calculate mixed strategies for games, but in practice most commercial games are so complex and involve so much uncertainty that no one can reduce the possibilities to mathematical percentages. Furthermore these mixed strategies are stochastic (probabilistic) rather than deterministic. While these mixed strategies are best for the “perfect player” they do not guarantee success the way a saddle point does.

"Contests"

Occasionally puzzles are turned into contests, where each player individually pursues the objective, and first one to achieve it wins. These can be described as “multi-player solitaire”: everyone works at a puzzle within a contest framework, and whoever does best by the “time” limit wins the contest. You can time how long it takes someone to do something and declare whoever is fastest the winner, but that’s not a game.

A race is a contest where there is some way to directly affect an opponent, typically by blocking their path, and that ability to affect other players moves the activity toward game and away from puzzle. But most races are closer to puzzles than to games, as the major problem is “how to go faster”, not “how to deal with opposition”.

Consider how different traditional Olympic speed-skating is from the newer short track style of Apolo Anton Ohno. They are both “racing” but the former is very close to a puzzle, while the latter includes a strong tactical element.

“Contests” are not games. Virtually anything that can be timed or measured can be turned into a contest. Nor does a contest require design, and if we call a contest a game then virtually everything becomes a game and we have a useless definition.

In “games” with more than two players, a contest will usually have symmetric starting positions, so that everyone has the same task. Games for more than two players with asymmetric starting positions are unlikely to be contests.

Failure

In a game, if you make mistakes or otherwise fail, you probably lose unless the opposition makes more mistakes. Trial and error (guessing then checking) is not suitable behavior, because while you’re guessing your opponent is likely to make better moves and win the game.

In a puzzle there is no danger of "losing"–if you fail you can just try again. Trial and error (guessing then checking) can be used to find the way. At worst you decide not to continue. Video games have enshrined trial and error through respawning and save points, when played as single-player games.

This has an interesting effect on player egos. Some people don’t like to put their ego on the line by playing and possibly losing a game against other people. On the other hand there are people who gain nothing from solving a puzzle and just feel stupid if they have trouble solving it.

Puzzles that are turned into contests typically maintain a noncompetitive attitude so that players don’t feel very ego-involved. Many Eurostyle boardgames are of this type.

Opposition

Games require intelligent opposition. Intelligent opposition can provide active obstacles/challenges and can adjust to another player’s moves. Puzzles provide passive

obstacles/challenges that have been devised by the designer(s) rather than the active opposition of other players.

In card Solitaire the obstacles are clearly inactive. In Tetris, there is purely random selection of the next block, not involving significant decision-making, not “active” to me. In Left4Dead, on the other hand, the Director is active opposition, changing the situation according to how well the players are doing. Computer programming provides the opportunity for an inanimate object to provide some form of active opposition, sometimes resembling intelligence. As the programming of computer opponents improves the computer can come closer to providing intelligent opposition.

A puzzle will present the same problem and solution again and again. In a game, the presence of intelligent opposition ought to mean that a variety of problems will be posed at a particular juncture, not the same one over and over. The presence of randomness and uncertainty can play a strong part here.

Origin of challenges

In a game the challenges come largely from other players, within the context established by the designer(s). In a puzzle the challenges come from the puzzle-maker(s).

Yomi

Games include the possibility of "Yomi", reading the intentions of the opposition; this is much more practical when the player is face-to-face with his opponents, able to read visual, auditory, and other clues, then online. In a puzzle "Yomi" is only possible if you can read the intentions of the puzzle creator; this is very difficult to do because the puzzle creator is not present offering cues to his intention.

Some games can be played as yomi if all participants are willing, yet if one uses a system solution, all end up conforming like it or not (Rock-Paper-Scissors is an example).

“Completion”

A play of a game may end, but the game can never be "completed", and you can never "beat the game". If the game is good there's always a reason to play again. I’m sure there are people who have played chess, checkers, backgammon, go, and other games more than a thousand times, and I know people who have played my game Britannia – 4 to 5 hours per play – more than 500 times.

Puzzles can be completed: there's no longer any reason to play once you know how to do the puzzle. You can "beat the game" [puzzle], and once you’ve beaten it there’s little reason to play again. Yet some puzzles, like many one player video games, have so much variety that you might play again.

Perhaps an in-between occurrence is a game that depends heavily on its story for its attraction. Once players know the story, many will stop playing the game. Many people enjoy a story because they want to know “what happens next”, and once they know that they’re no longer interested in the story. Other stories are timeless and can be enjoyed over and over.

System versus psychological

Games, especially those with more than two players, have a strong psychological component; players mostly contend with the other players, not with the system. Puzzles have little or no psychological component; player(s) mostly contend with the game system, not with the other players (if any, as in a contest).

In video game terms we can call the psychological PVP (player versus player) and the system PVE (player versus environment).

Two player games tend to fall in the middle. There are no opponents to persuade, just someone who controls the other side. But that person can be misled or befuddled. (Actually warfare is “two player”. Yet Napoleon said that in war the moral (psychological) is three times more important than the physical (system).) While you can try to psychologically manipulate a single opponent you must also understand the system very well or no amount of psychology will save you from losing.

A “game” that's pure system is a puzzle, one that's pure psychology is a game.

Conflict

Games (like stories) usually involve direct conflict amongst participants. Puzzles lack conflict (though there are obstacles), in considerable part because there’s only one participant. Puzzles that are turned into contests rarely have direct conflict but there may be indirect conflict in the form of obstruction, something like a race.

As you move toward the game end of the spectrum and away from the puzzle and it's more likely that there will be obvious conflicts between players.

Story

Both games and puzzles may have an explicit story component. If the game depends heavily on the story component then once players have experienced the story they may no longer play. More often, the story provides a marketing hook and a context for play, but the quality of the gameplay is what will determine whether people keep playing the game.

The story component of a puzzle provides a context for what the player is doing and consequently could include hints about how to solve the puzzle.

“Mastery”

A game--unless it is very simple, such as Tic-Tac-Toe or Rock-Paper-Scissors--can never be entirely mastered, it always depends on the quality of opposition. Puzzles can be completed. Puzzles can be played “perfectly”. Those with point scales can be played to improve mastery (high score). Arcade Pac-Man is a puzzle finally completed by someone after many, many years of play. Up to that point, the point score indicated mastery.

Randomness and Uncertainty

A game need not have randomness or uncertainty, though a two player game with neither is probably solvable and is really a puzzle, for example chess or checkers. Randomness and uncertainty can be present in something that still conforms to most of our puzzle characteristics; there can still be dominant strategies although there are unlikely to be saddle points.

Many puzzle solvers do not like randomness. For example a reviewer in Gameinformer magazine noted that "combat was accurate and satisfying--when we missed it was because our aim was off, and not because we came up short on some hidden die roll."

Other puzzles have some random element to provide variation. The player optimizes what he’s going to do in light of the knowledge that there is variation.

Do we have to say that elements of randomness or hidden information are necessary for something to be a game? Not exactly. While theoretically chess is a puzzle, in practice no human is able to understand "the solution", even computers have not yet attained it although they will. So while technically chess is a puzzle we treat it as a game.

Where do game and puzzle meet?

Puzzles versus problem-solving

There has to be a vast gray area where game and puzzle meet. What identifies or characterizes it? One difficulty I've had in differentiating puzzles and games is determining at what point the capabilities of a powerful programmed computer can mimic intelligent opposition, and also at what point puzzle-solving becomes problem solving.

Games certainly involve problems to solve. Where does puzzle-solving become problem-solving? From the player point of view, I'm not sure. From the designer point of view, it may amount to this: when someone devises a puzzle, he or she has in mind a particular way to solve it. And might not even allow other solutions that, in real world terms, ought to work, but won't in the "game". On the other hand, when someone devises a problem to solve, they don't have a particular solution in mind, they pose a situation and let the player figure it out.

When you have uncertainty (if only about the human participants’ intention) or chance involved, you often have problem-solving; if you have no chance, and only uncertainty that can be predicted absolutely (you know what possible shapes are coming in Tetris, there is no human-unpredictability) then you have puzzle-solving--because the solution always works.

Here's another way of looking at it, from a discussion of the future of video adventure games in PC Gamer magazine #217 (Richard Cobbett). Recall that adventure games are traditionally narratives expressed through puzzles.

Puzzles need to be largely retired in favor of problems. What's the difference? With a puzzle, the challenge is working out how the designer wants you to solve it; a problem is something that you solve on your own. A puzzle is something you get stuck on; a problem has consequences and those consequences are all the more effective because you're more responsible for them. [Emphasis added]

By this definition many single player video games have moved beyond puzzle to problem. But by this definition a "problem" is still closer to a puzzle than to a game.

Hybrids

Many modern "games" are hybrids of game and puzzle. We can recognize that formal puzzles tend to be pure puzzle and some games tend to be pure game but there can be a mixture in many others. For example many games players can benefit from being able to calculate probabilities in a game. One version of Settlers of Catan that I own includes a table of probabilities for sums of the roll of two dice, a vital facet of the game. People who understand the probabilities will play better than those who do not. This calculation of probabilities is a solution, there is just one right way to do it. In that respect it's like a simple puzzle in the midst of a game.

While Settlers is a simple example familiar to both tabletop and video gamers, there are many AAA list games that rely heavily on computer opposition. Varying with the success (and designer intent) of the "AI" we have a mix of game and puzzle as the computer opponent more or less successfully mimics a human opponent.

Uncertainty revisited

With all we've said about uncertainty, however, we can harken back to our first generalization, that games are about people and puzzles are about calculation and logic.

Where there is no uncertainty, I'm not sure you can have a game in the long run, although if there's enough complexity then that provides a form of uncertainty. Tic-Tac-Toe does not provide enough complexity to create uncertainty and so it is easily solved despite best efforts of the opponent. To the human mind chess provides a great deal of uncertainty because of the complexity. But it's likely that computers will solve it someday, just as they have solved checkers.

When I was a kid I was a determinist, thinking that if you had a sufficiently powerful computer and enough knowledge then you could calculate everything that was going to happen. The Heisenberg Uncertainty Principle, among other things, put paid to that notion. While theoretically the mathematical Theory of Games of Strategy enables a "perfect player" (one who is maximizing minimum gain) to identify possible strategies (moves) and calculate the percentage of time he should use each one in a given situation, this doesn't mean the game always happens the same way, it will vary at each play with the dice rolls that pick which strategy you use THIS TIME. Well, it does play the same each time if there's one strategy that should be used 100% of the time (Tic-Tac-Toe), but most games are more complex than that. So each play of the game can be different even if it is solvable.

Yet in practice the "determinist" view, which might be that you can always calculate the right mix of strategies, is impossible in the real world. Among other things it's usually impossible to agree to the value of particular results when using various strategies. Chess programs used to be written that way, relying on values of squares or pieces or positions, but I'm guessing that nowadays they're mostly brute-force look-aheads, given the speed of big computers.

Games are not all math, nor is game design primarily a mathematical exercise. When it approaches a mathematical exercise, the design is probably a puzzle, not a game. You might be able to say that "all puzzles are math," but games are not.

Number of players and player interaction

While we cannot say that a game must have randomness, I think it must have uncertainty. That uncertainty can come from having more than one opponent. Diplomacy is a classic boardgame for more than two players that has no random element, but lots of uncertainty through seven players, compounded by the simultaneous movement method. A two player game can have uncertainty about the other player's intentions, but because there is only one other player then you can try to account for all possibilities in a way that is usually impractical with more than one opponent.

You can have more than one or two players when you have a puzzle that has been framed as a contest. Many Eurostyle boardgames are constructed this way. I don't think people often consciously think of Eurostyle games as puzzles, but in practice they treat them that way, as something to be solved. It's not at all unusual to see Euro players helping each other during a game to make closer-to-optimum moves. If every player is getting closer to the solution to the game, they can feel good about themselves even if they "lose" that particular play. More broadly, people are playing against the game system far more than they're playing against other players. There are lots of exceptions in this enormously broad category, of course, and some of the most popular Euros are far from puzzle-like.

What about player interaction? (This is interaction within the game, not social interaction amongst the players.) "Multi-player solitaire", which often amounts to a puzzle-contest, is by definition lacking in player interaction (“solitaire”). On the other hand, how can you play a game with other players if you cannot interact with them in the game? Can a puzzle have interaction with other players? As always with computers, we can ask ourselves how much a computer can substitute for a human.

I think that player interaction is one of the defining characteristics of games, one that is missing from puzzles. There tends to be less player interaction as the “game” is more puzzle-like. You can have a poorly-designed game, such as Monopoly, that has little player interaction because of poor design choices rather than because it is puzzle-like.

"Yomi"

David Sirlin's outstanding book "Playing to Win" on playing video fighting games is full of the psychology of play and "yomi" (reading the opponent’s mind)--but he's talking about a two-player game, not a one-player-and-computer game. http://www.sirlin.net/ptw .

There is no Yomi, no reading of the minds of the opposition, in a puzzle, because there’s no opposition. To generalize, the more Yomi can help a player succeed the more we have a game and the less Yomi can help a player succeed the more we have a puzzle. In a pure puzzle Yomi is useless except in that strange case that you somehow divine what the puzzle-maker was doing. In a pure game the player who is best that reading the minds the opposition will probably be most successful.

An important distinction is whether the opposition is also trying to rely on Yomi or is trying to rely on Game Theory. If someone is minimaxing, and relying on a stochastic method to determine which of a mixed set of strategies to use, Yomi is useless. But in games of significant complexity few players will be able to figure out mixed strategies.

For example in Rock-Paper-Scissors (RPS) the Game Theory solution is play each choice one third of the time. And that is quite literally the way I would play if I had a randomizer available, that is I would play each possibility one third the time. Other people try to outguess the opposition, to use Yomi. If both players are trying to do that then the one who is better at it will probably win in the long run. But if someone is trying to use Yomi against me it won't make any difference, in the long run the game will still be 50-50. (At least, I think it will still be 50-50, I don't think the other player will do worse because he's trying to guess.) So in one sense RPS is all about Yomi and in another sense it is solved.

After all, the intention of the game is to determine something randomly. (Odds-Evens is even purer: each player "throws" one or two fingers, one having taken an "odd" to win and the other an "even" sum.)

Tic-tac-toe is practically a puzzle because it's so easy to solve, although people who haven't solved it may use Yomi when playing. This may work if both players are trying to use Yomi, but if one follows the solution, the game will end in a draw, period.

Poker is an epitome of Yomi. Players who best divine what the other players are trying to do are the most successful in the long run. The system is easy to figure out and relatively easy to calculate odds for, although there are some people who cannot do it. So lots of people know the system of playing poker, but a lot of them are not very good at it because they're not good about hiding their intentions and divining other players’ intentions.

I'm often surprised that people play poker online, because many of the signals that provide information for Yomi are not available. All you have left is trying to analyze the pattern of play of the opposition.

Another way to put this is that a puzzle is challenge without Yomi. And without the unpredictability of human intervention.

Game Design Books

What do some well-known books have to say about games and puzzles?

Rollings and Adams in Fundamentals of Game Design give a simple definition of the difference between toys, puzzles, and games. Toys have neither goals nor rules. You do whatever you want with them. Puzzles have goals but not rules. And games have both goals and rules. This is a useful rule of thumb, yet I always have a problem with this definition because most puzzles do have rules even if they are not explicitly written out. For example, if you’re trying to work one of those puzzles with string and wire one of the rules is you cannot cut the string. Let me illustrate it this way: Alexander the Great, when confronted with the extraordinarily complex Gordian knot, clearly a puzzle, broke the rules by using his sword to cut the knot.

On the other hand some tabletop role-playing games specify no goals, but players have their own objectives.

Zimmerman and Salen in Rules of Play after 80 pages constructing a definition of games find that puzzles ("The Puzzle of Puzzles") and role-playing games don't quite fit. In the end they punt: "We are not going to split hairs. In our opinion, all puzzles are games, although they constitute special kind of game." I refuse to punt: the differences between puzzles and games are fundamental and of great importance to designers.

I think any book that approaches game design from a video game point of view is trapped by the past: people call single player interactive entertainment software "video games" even though there are so many puzzle-like characteristics to single player video games. Dear Esther is neither game nor puzzle, but it is sold along with video "games", so it’s reviewed in computer “game” magazines. Wii Music and Wii Fit are also not games or puzzles, but are marketed by a video game company (Nintendo) along with other video games, so we tend to call them games. A more practical/descriptive name for the video game industry is the video entertainment software industry.

The glossary in my forthcoming book "Game Design: How to Create Video and Tabletop Games, Start to Finish" has this entry for "puzzle":

Formal puzzles have a unique solution, and once you've solved the puzzle there is little point in playing further. Many single player video games are interactive puzzles, some with a single solution where there’s no random factor, some (which include randomization to avoid complete predictability) with “optimal ways to do things”–dominant strategies and tactics. Games, in contrast, cannot have “solutions” or a dominant strategy because of the unpredictable and infinitely-varying influence of the opponent(s).

Designing games versus designing puzzles

Both games and puzzles need to be designed. But the objectives and methods are somewhat different because the method of posing of challenges is different (from other players, or from the system). Design overlaps, but there are parts of game design that have nothing to do with puzzles, and parts of puzzle design that have nothing to do with games (see diagram).

From a design point of view, it’s a lot easier to test a puzzle than to test a game. You only need one person, except for puzzle-contests, and you don't need to design something that can be enjoyably played a hundred times, because people typically play puzzles only once, or a few times–only until they know the solution. On the other hand, games can usually be simpler than puzzles, because the players provide much variation.

An example, which is which?

Recently I thought about definitions of game, puzzle, and toy in relation to three gambling activities: Texas Hold'em, Blackjack, and Slot Machines.

In playing slot machines there is nothing to solve, no opposition, pure chance–but it isn’t quite a toy, because you can’t change anything to suit your own desires. Is it just an activity?

In BlackJack, there is no opposition except in a programmed sense, and it can be solved (by the card-counters over the course of a session, not individual hands). It's a puzzle.

Texas Hold'em is all about what’s in the mind, though there is also considerable chance, you can make all the right choices and still lose. As with BlackJack, you must look at it by session, not by individual hand. An individual hand played in isolation is much more like a puzzle as you try to calculate your odds and the opponent's odds.

Another example

Consider the "game" show Jeopardy. Is this a game, a puzzle, somewhere in between? Most of what the players do is answer trivia questions. The only mechanism that lets a player affect another is to "beat them to the buzzer," to answer a question before anyone else can. There are possible psychological effects that are aspects of the contest, and even a small chance for "yomi" when the players choose how much to bet/risk on the big bonus.

If players took regular turns answering questions, this would absolutely be a puzzle-contest. The buzzer introduces a way to hinder other players, or at least to help yourself at their expense, and takes Jeopardy a distance toward game (a form of race) and away from puzzle. It is still much more puzzle than game.

The bottom line

Games are about people and psychology, puzzles are about systems, about calculation and logic (and, if all else fails, about guessing (trial and error)).

Game designers devise ways for players to challenge other players. Puzzle designers devise ways for the puzzle (perhaps implemented through a computer) to challenge the player or, in a puzzle-contest, to challenge all the players. Many games involve both.

[The editor has not liked my diagram. It is a simple Venn diagram of game design and puzzle design with an intersection between the two.]

Games

Games How to resolve AdBlock issue?

How to resolve AdBlock issue?