- Staff Blogs

- Blades in the Dark - A Minor Complication, Pt. 1

Blades in the Dark - A Minor Complication, Pt. 1

HotOn Blades in the Dark and the surprising joy of failure.

1.

We text Anatoly, telling him we need his silver tongue and we need it, like, right now. He’s currently at a welcome dinner for a summer teaching program and we’re not sure if we can reach him. However, the orphans don’t care about the job he’s wrangled for summer break. The headmaster of their orphanage-slash-spy-nest has just been murdered accidentally, having been blown to bits by an ill-timed explosive meant to professionally breach the wall of his office.

Though the band of interlopers will admit that this was, in fact, not-so-professional, they are able to coax his (rather surprised) ghost to reveal the location of Dr. Julian Blank’s evil lair. Long story short, the hidden subterranean laboratory is blown up, the disembodied spectral hands keeping the children subservient disappears into the ether, and all that’s left to do is convince the children that, though they are technically free to do as they please, wouldn’t it be better for everyone involved to hold off on unionization for just a little while? This is where Anatoly’s particular skillset comes in:

While we can’t recreate his particular accent, a self-described Rocky & Bullwinkle imitation, we read the words aloud. Then it’s time to measure his success—do the orphans buy his particular blend of faux-Russian chicanery? It’s time to roll the bones and find out.

Three dice skitter around the table. Two threes and a four. Translated via our strange shared language, this means that our lovable bunch of orphan-spies have come to a consensus that we can be trusted. Sort of. For now, at least. But already, seeds of discontent are starting to sprout, setting the stage for future shenanigans, mishaps, and betrayals. In gaming, as in life, no one gets away totally clean.

2.

Blades in the Dark is a tabletop roleplaying game designed by John Harper. In it, players take control of a band of thieves and cutthroats in a filthy, low-fantasy industrial city powered by demon blood and haunted by ghosts. More than any other RPG I’ve played in my life, Blades in the Dark delivers on the promise so many game systems make: it generates stories.

I don’t just mean the stories that play out as everyone is sitting around the table, making decisions in character, and stitching together a plot from a series of dice rolls—lots of games do this, and do it well. Rather, Blades creates the kind of stories that stick in my brain and ferment long after the fact, bubbling up many months later and making me laugh out loud. More than that, Blades creates stories I love to hear about even when I’m not involved with the game in question.

Usually, listening to other peoples’ role-playing stories is sort of like listening to other peoples’ dreams. This is to say, it’s the ultimate form of saintly indulgence, being that it’s almost always an absolutely horrible experience. These kinds of stories often revolve around a supposedly “hilarious” thing someone did in character, or a particularly “crazy” result of a die roll, or a game master’s plan going wildly awry. This isn’t a bad thing, necessarily—I swear I’m not trying to take away anyone’s fun! But roleplaying tales tend to traffic in “you had to be there”-isms that make for enjoyable telling and dull listening.

So why is Blades in the Dark different? Why do I read about randos’ sessions on Reddit? Why have I actively sought out Blades Let’s Play podcasts? It’s because this game does one thing better than any other game I’ve ever played: failure.

3.

Dungeons & Dragons sucks at telling players no. Don’t get me wrong, it excels at a lot of things, but it’s a game that’s fundamentally built for success—introduce failure into the system and it freezes up, unsure how to process this negative input. Messing up in D&D will generally slam a door shut: you botch a roll and jam the lock on a treasure chest, you pick a fight with a monster above your skill level and end up dead, you take the left path when the dungeon master was absolutely certain you were going to go right and all the sudden she’s breaking a sweat and flipping madly through the Monster Manual to whip up a quick encounter.

When the game recovers from this kind of setback, it’s generally due to the dexterous improvisation of a skilled DM. She can futz about behind the scenes and do what it takes to get the party back on track once more. But even when this sort of obstacle is overcome, it’s not without consequence: for a brief moment you can see the curtain swing open and witness the wizard frantically working the levers. The spell is, at least for a moment, broken.

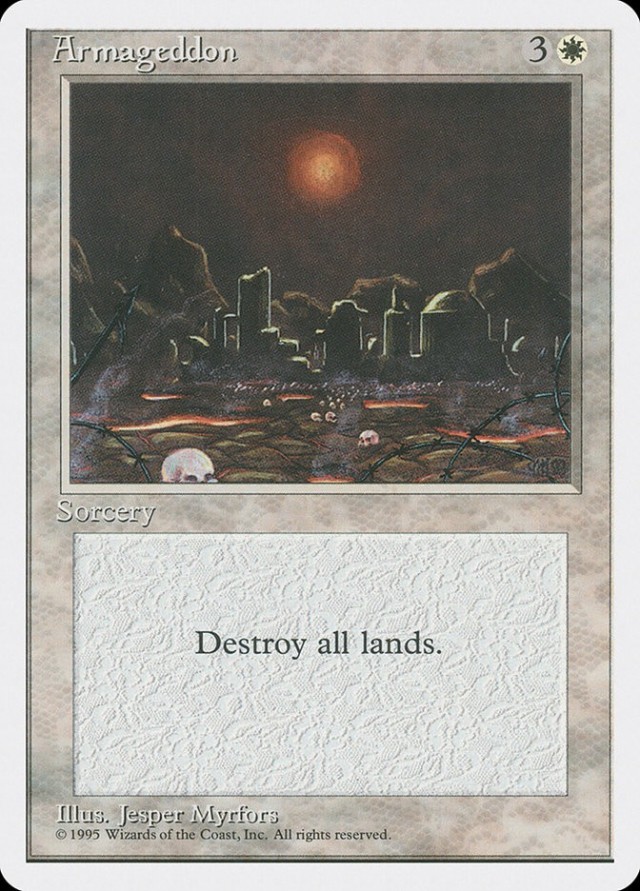

I chalk this up to tabletop roleplaying’s prehistoric ancestor: the competitive wargame. In this sort of head-to-head contest, success and failure are both equally dramatic, since it’s a zero-sum situation—what benefits one player hamstrings the other. When only one person can prevail, this kind of winner-takes-all conflict creates real and meaningful drama, therefore also creating real and meaningful narrative: a record of the ups-and-downs of that evening’s battle.

These kinds of competitive mechanics struggle to fit within a game whose primary goal is collaborative storytelling. Genre holdovers like opposed combat rolls and pass/fail skill checks create momentary drama, but if they tend towards anything other than the triumph of the player characters they can be demoralizing and narratively deflating. Failure can make roleplaying mechanics feel pointless, or worse—it can turn the game into a kind of confrontation between the players and the game master that will ensure no one has a good time.

4.

Where more traditional games can falter, Blades in the Dark shines. Not only does it create a space where failure is acceptable, it actively harnesses failure and uses it as narrative fuel to propel the story forward. Resolving a risky action in Blades couldn’t be simpler—you build a pool of dice, give them a roll, and look for the highest single die result. The rules for interpreting this number are what translates this system into something sublime.

It’s rare that the game hands you an unqualified success—when this happens it’s a thing of beauty, and the table will cheer. Most of the time, though, the results of your action will be a little murkier. Eschewing the “yes / no” binary, the game traffics in “yes but” or the even scarier “no and also,” mechanical consequences with serious narrative effects.

Let’s say your intrepid thief is trying to pickpocket a guard, and just barely makes a successful roll. What happens then? The game master gets to impose a new condition, putting your character into just a little more trouble. Maybe the guard feels a little itch and reaches back to investigate. Maybe you have the key in hand, but it remains tethered to the guard’s belt. Maybe you have a brief window in which to do your dirty deed before the guard tries to open a door and realizes something is missing. Three minor complications, all with tantalizing new narrative paths to follow.

Even the ultimate roleplaying consequence—kicking the bucket—doesn’t bring the story to a halt. An event as dire as a player character getting stabbed in the heart just sets off a new chain of decisions and possibilities. New directions for the game to take, new and memorable moments to share with your friends.

Blades in the Dark has altered the way I look at success and failure within roleplaying games. This is not to say that other games don’t have interesting things to say about player outcomes, or that the system is a work of unimpeachable genius. Rather, its power is in the way it uses a clever series of mechanisms to reinforce the game’s thesis on failure: it is far more fun for the characters to work their way out of trouble than it is to avoid it in the first place.

One of Blades’ core principles is that players should drive their characters like a stolen car. I take this to mean that players shouldn’t invest in their characters’ well-being or supremacy but instead should revel in the consequences of their artful recklessness. It’s why we should be pleased as punch at moments of utter failure and compromised success, and it’s why I’m beyond delighted that, despite our best efforts, the orphan-spies are planning to stab us all in our sleep.

This is the first entry in an ongoing exploration of Blades in the Dark, cooperative storytelling, and the nature of failure. In the next installment I'll examine what it means to sacrifice personal cool on the altar of story, and why we should root for the bad guy whenever we can.

Games

Games How to resolve AdBlock issue?

How to resolve AdBlock issue?