Sorry you've got another F:AT looks back this week, but I've just come home from holiday and prior to that a minor family crisis and I've not had time to get something together. I've also got big voluntary programming project coming up which will eat into my writing time so you may see a few more of these in the coming weeks. Sorry. But some of the old blog material is reasonably good. I picked this one because I've been asked to post a few more session reports, and although this isn't one of the cool narrative ones I post occasionally, it does showcase my favourite game, and it does offer some interesting insights into gaming.

Sorry you've got another F:AT looks back this week, but I've just come home from holiday and prior to that a minor family crisis and I've not had time to get something together. I've also got big voluntary programming project coming up which will eat into my writing time so you may see a few more of these in the coming weeks. Sorry. But some of the old blog material is reasonably good. I picked this one because I've been asked to post a few more session reports, and although this isn't one of the cool narrative ones I post occasionally, it does showcase my favourite game, and it does offer some interesting insights into gaming.

I know I don't really use my blog space for what blog space is usually used for - rather than telling everyone about the games I've been playing and spewing forth amusing anecdotes from my game evenings I tend to prefer to get on my high horse and preach at everyone. I make no apologies for this - I thoroughly enjoy doing it, and if I sometimes come across like a lecturing professor then so what? But today I'm going to something different - I'm going to do the usual blog thing and tell you about a game I played.

And then I'm going to preach at you.

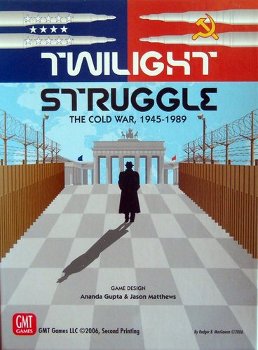

The game in question was Twilight Struggle, one of my absolute favourite games. It was played over the fantastic free facilities over at WarGameRoom. I, a moderately experienced player was playing the USSR against a considerably more experienced US player.

One of the reasons I wanted to flag up this particular session for public consumption is that is showcased everything that's brilliant about Twilight Struggle. Every hand was loaded with tense, agonising decisions about best plays and risk management. There was luck in the game that helped it swing one way and the other to groans and cheers from the players involved. It's possible that luck, in the end, decided the game and although I don't think it did, the bottom line is that TS is just so much fun to play that really, who gives a damn if it does?

The opening few rounds went pretty smoothly, with no great changes in either direction. Europe and the Middle East were balanced but I'd managed to get into a strong position in Asia, having gathered North Korea, Pakistan and India and when Asia scoring came out I took a small lead. I also absolutely raced up the space race track leaving my opponent standing in the dust.

Things started to get a bit wobbly for me in the mid-game. I made a textbook mistake in Europe, being suckered into participating in a race to get control of France and then being hit by the dreaded "Truman Doctrine". However, my opponents' play of "De-Stalinisation" gave me the chance to grab battlegrounds in South America and Africa - since I already had Cuba thanks to "Fidel" I was in a strong position in those countries. Having gained control of these important areas I made a decision to use the points from "Decolonisation" to usurp the US in SE Asia, gathering Thailand, Indonesia and Laos for my troubles. However I then got hit with "Voice of America" or whatever it is that cleared out my influence in Africa and South America, which put me in a real bind having only Asia and Central America to score from.

The real disaster came in turn seven. I had a hand full of scoring cards and I got hit with Pope John Paul, Ussuri River Skirmish and the China card all in one turn - I lost Poland, North Korea and Pakistan and there was nothing I could do about it. I spent the next two turns desperately fire fighting - the scores were pretty much equal and I managed to claw my way back into parity in South America and gain a slim domination of Africa. So now I had Africa and Central America ranged against Europe and Asia for my opponent - the big scores at the end of the game were his.

However, in turn nine I also managed to loose control of East Germany (I don't now recall how this happened) and I thought my number was up as my opposite number had complete control of Europe. My last few cards on turn nine were to hit the enemy with "Quagmire" which basically made him miss one turn and then in sequence cram in "Soviet Governments" to make him loose control of West Germany and "Willy Brandt" ( the first time I've ever played that card as an event) to give me a foothold.

Then the game crashed.

So we hooked up again in the WarGameRoom chat facility and I basically offered him the game but he talked me into playing out the last round. My headline was the dreaded "Red Scare" which reduced the points he could pour into Germany this turn. The first few cards we were just battling for control of West Germany. Then my opponent played "tear down this wall" to give him a free realignment attempt at West Germany. Muscles were tensed, breaths were held and... it backfired spectacularly as he actually lost influence, giving me control of the country. He'd burned all his best cards and I used my last few cards to minimise US scoring opportunities in other regions and make sure he couldn't get his military ops for the turn. I thought I'd lost it.

When the final scores came in, I winged it by a measly two points, and rejoiced.

So, a great game. But it occurred to me afterwards that there were a few lessons that I ought to take away from the game.

First and foremost, never give up. Watching people in games whose world has collapsed around then get all sulky and throw in the towel has to be one of the most pathetic sights in the world. I've long since learned not to sulk when it happens to me, but to appreciate the fine play of my opponents and enjoy my spectacular demise for the fine gaming spectacle it often is - but I still frequently resort to giving up when it happens, as illustrated by the game above. But I played the last round and snatched victory from the iron jaws of defeat thanks to a combination of luck and poor play by my opponents. Keep going to the bitter end - you never know what might happen.

The second lesson is that this is a fantastic illustration of why random mechanics and thematic games have the ability to create more exciting and memorable gaming moments than more tightly scripted games. A level-headed analysis of the situation would run something like "we played a game for two hours, and a last minute dice roll was a significant factor in determining the final winner". But that's to miss so much - I only pulled out the last minute win because I'd played well enough over the preceding rounds to stay in touch, and in the end, random win or not, we'd both had a fantastic time and come away with a great gaming anecdote to bore our friends with.

And the third lesson is probably the most important lesson in gaming - however viciously, desperately, achingly you want and play for that all-important win what matters at the end of the day is that you had a laugh doing it. A big part of how I learned not to sulk when the players gang up on me or the dice go against me is to remember that my gaming experience is just part of a wider narrative, so if you're going to go down, don't go quietly no matter how pointless your situation is. It might just be that you swing the game in one direction or the other, even if it's not toward you, and it might just be that you pull off the mother of all spectacular collapses or even comebacks that everyone will be talking about for months to come.