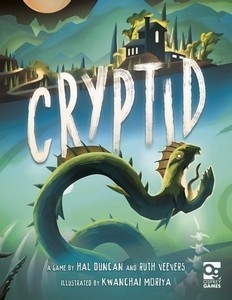

Crytpid isn't out yet, but nevertheless, it sits on the table, a cryptic puzzle: at once real and unreal. Of course, it draws players like a honeypot.

"I've heard about this!"

"How did you get it?"

"Have you read the rules yet?"

Turns out that I have because it's a gloriously simple game. So simple that I have visions of playing it with my family. But we're starting here at the game club, so I explain. We draw a card and assemble the pictured map from six modular pieces. It's a hex map of an empty, echoing wilderness, made of different terrain types. Some are animal territory, full of roaming bears or cougars. Then we place coloured wooden pillars and triangles to represent standing stones and empty shacks.

After that, everyone gets a coloured booklet and a set of pieces. On the reverse of the map card, there's a series of colours and numbers in a cross-reference. You find the number in your colour, open your booklet and look it up. Mine says "The habitat is within three spaces of a blue structure". We're cryptozoologists, hunting for a mysterious monster and, at the start of the game, this is the only information I have about where it lives.

I look up from my explanation and see everyone is hanging on my every word. So I sigh, knowing I'm about to puncture a bubble, and explain we never actually know what the creature is. It's a deduction game. Each turn, a player asks a question of another player. In answer, they place a disc or cube to show whether that hex could, or could not, be the creature's habitat according to their clue.

That's the whole game. Or so I thought. "What kinds of clues are there?" someone asks. I'm not really sure why that's relevant, but I show how the clue formats are all printed on the back of each booklet. On one of two types of terrain, for example, or within one space of an animal territory.

At first, no-one knows what to ask of who. There's no information to go on. But as the first few cubes and cylinders go down, a strange thing begins to happen. Out of nothing, a vague order begins to form, like salt crystals materialising out of saline. You can barely seem anything at first, wisps of white fluff at the bottom of a bowl. And as time goes on things become harder, sharper until you wonder whether there was every any water there at all.

We sit, trying to pull together the strands of what we're given. And all of sudden, I see why knowing the clue types are important. It allows you to reverse engineer the patterns in clue placement. Then you can guess what other player's clues are and put them together to find the habitat hex. I am fearful, wondering what my questions and answers might reveal about my own clue, and whether anyone has guessed it. But I also know, now that despite its simplicity, this is no gateway or family game. The logic chains are too long and cumbersome for that.

Wood slides on cardboard. There are a few complaints about the generic nature of the components, and it's hard to argue. The game looks like an abstract rather than a desolate lost world. Two of the player colours are also irritatingly similar under the harsh strip lights of the hall.

Other players suck their teeth, exchange knowing winks and glances. I look at the board in bafflement, looking for the crystals, but they're not there. It's a fast game, turns passing quickly, detail flooding into the empty board. My brain clutches at the strands of information, seeking pattern and clarity, finding none. Everyone, I notice, is leaning closer and closer to the board with every placement, as if proximity is the answer.

Then, all at once, I see how I can work out one player's clue. It's like a magic filter over the board, having seen one I can see others. A moment later I can see them all and I have it! I know the answer! I wait, itching for my turn to come. The player before me picks up his pieces, extends a finger and points at a hex.

"There," she says. "Is that the habitat?"

It's the hex I'd earmarked. On a guess, everyone has to place a clue on the board in turn until one places a cube, indicating failure. Tension cranks as cylinder after cylinder goes down until, with the last one in place, she's won. If only I'd figured out the patterns one turn sooner!

Five gamers are around the table, the game's maximum number, and none of us recalls playing anything like this before. So we set it up again, find our clues and get quizzing each other. But after a few turns, confusion begins to set in. Something isn't right: no crystals seem to be forming. Another ten minutes later, one player consults his booklet and pales in horror. He's read the wrong clue and, in doing so, ruined the session. Amid profuse apologies, we pack up and play something else.

Yet the sheer novelty of this curious Cryptid nags at me like the possibility of a lottery win. I reach out to one or two other lucky people who got advanced copies to solicit opinion. One found they kept running out of pieces. Another points out there's supposed to be an app for the clues to make it clearer than the booklet, but it's not out yet. There is a play Cryptid website, though, which fulfills the same function.

So it gets broken out again, with friends this time. The website simply proves too clunky to use in practice: people want to check their clues. I explain and emphasise that you need to be very careful playing Cryptid. That you need to be absolutely sure of your clue and every placement you make, that a single mistake can derail everything.

Everyone seems to get the message. And as the crystals start to solidify on the empty board, it feels to me like the danger of a spoiled game is worthwhile. The thrill of cryptid hunting is taut and raw and almost as novel as the weird creatures themselves. But I wish that, just once, the reward for catching one could be more concrete than mere victory and a soft tug at the corners of the imagination.

Games

Games How to resolve AdBlock issue?

How to resolve AdBlock issue?