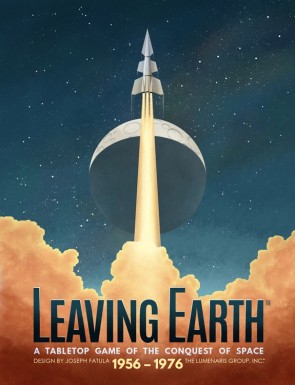

You know I had a big intro for this article written, about sinking aircraft carriers, finding grails and bagging chicks, but it’s all just a distraction from the real topic. It's a good one; let’s talk about Leaving Earth.

I just don’t make it to game night very often anymore. This past Monday I made it and arrived late, so when I came in they had a big session of Betrayal going on the main table. I moved to the table on the patio and started sorting out Leaving Earth, planning to play a solo game first to get the rules down. The rules are fairly long, but really pretty simple.

As I'm setting it up two other guys come over to the table looking to join in, then another. A four player game is suddenly in the works, and plenty of eyes and ears on the rules will certainly help. We played on the "normal" difficulty setting.

Leaving Earth is about the early years of space exploration. Each player plays a different country, USA, Russia, Japan, France or China. The roles are symmetric, all players have the exact same materials to work with. In some games that’s a knock, but not in Leaving Earth, because there’s plenty to take into account without a special power to give the game flavor. Your job is to successfully achieve big goals in space by developing the engineering needed to do the job. Some goals are small -- one of ours was to put a man through a suborbital flight. Some goals are crazy big, like going to an asteroid, collecting a sample and returning it to Earth. The goals are randomly selected each game though I suppose you could choose what you like from the list. We pulled them the official way and got a nice mix of big and small.

So, let’s pretend you’re going to the Moon, the same way Apollo engineers did in the 60s. You need to put enough stuff into Earth orbit to go to the Moon and back. And in order to go to the Moon from Earth orbit you need to bring enough stuff from Earth orbit to get into the Moon’s orbit, and then you need enough stuff in the Moon’s orbit to go down to the Moon, land there, then have enough stuff to get back to the Moon’s orbit, then back to the Earth’s orbit, then back to Earth. You need a lot of stuff, and the stuff for each step needs to be brought with you one way or the other along for the ride for all the steps that precede it. So you may be going to the Moon, but the first thing you need to figure out is “re-enter Earth’s atmosphere”, because everything you need to do that needs to either go the whole journey with you, or be pre-positioned to be picked up along the way. Each prior step gets added to the bulk you bring, and . . . well . . . you get the idea. They call it Rocket Science for a reason, and it gets much more complicated when you’re going to Mars or to an asteroid even farther out than that.

As the youngest baby boomer on Earth I remember the Moon shots in no small amount of detail. Being an adolescent boy during the space race kicked ass, because the space race kicked ass. It wasn’t just about getting there, it was about getting there first and both NASA and the Soviet Kosmicheskaya took pretty big risks to make that happen. This was tech on a razor’s edge and everyone watching at home knew that. Plenty of missions blew up, and took people with them on more than a few occasions. That kept things pretty dramatic. Nobody on your TV said that what you were looking at was probably going to work, because no one could make that promise.

Well here’s the thing – Leaving Earth isn’t making that promise either. There is plenty of room for shit to go wrong in this game, and one play, sometimes one turn, is all it takes to figure that out. If ever a game married its thematics to its mechanics this is it. Leaving Earth does something magical – it makes missions hard, but provides a way for you to get better at them if you’re willing to take the time and the money to do it. That’s the rub in the game. This is a race. Time is of the essence, money is tight, but you need to burn both to succeed.

This was a first game, so there was a lot of pointing and asking and figuring things out. The rules were quite simple, but making your missions work is another story.

This was a first game, so there was a lot of pointing and asking and figuring things out. The rules were quite simple, but making your missions work is another story.

The biggest hurdle I had to overcome was that the game pieces don't always match what they did historically. I know the programs of the era, and I know what the equipment on the pieces was designed to do. So as a first time player (born in 1964) taking an Atlas rocket to start seemed obvious, as it would get a man into orbit. That's what it did in real life. But in the game an Atlas is suborbital at best, or useful for a mid-course burn if you're going to the Moon or Mars. This inconsistency is almost assuredly the output of balance and playability tuning, and it’s fine. My Atlas technology served me well later in the game. But early on I had to get past the historic part and keep my eyes on the numbers. Though everything was fine relative to each other (Atlases are smaller than Soyuz, which are smaller than Saturns, etc.) their capabilities weren't a perfect match with reality. A minor knock.

So you get $25 million dollars per turn to purchase research (e.g., Atlas Rocket Technology) and also to purchase actual products of the research. All technology items cost $10 million to research and they’re not just big metal things. Technology includes process engineering as well, like Rendevous in Space or Surveying. For things like rockets you need to purchase actual manufactured goods as well, so getting your first Atlas upright on the launch pad will set you back $10 million for the research and $5 million more for your build. Space ain’t cheap, and you get $25 Million non-retainable dollars per turn.

But here’s the thing. You gotta ask yourself this question when you’re playing Leaving Earth – can you really, really test docking two ships floating freely in space without sending them up there to do it? The specs look good on paper . . . but you don’t know what you don’t know. So everything you research in Leaving Earth comes with a hidden risk factor to it, in the form of three little cards. Most of them say Success on them. Some of them say Minor Failure on them. Others say Major Failure on them. For each component of your planned trip to Mars, or the Moon, or Mercury, or wherever, these three random-draw cards provide a pucker factor that keeps you humble in spite of your mathematical genius. Because each time you use that technology you turn over one of those three unknown cards.

So, for example, I wanted to put a probe past the Moon on a surveying mission. I had a Saturn booster, more than enough to put my probe and its booster into orbit. When I fired off that Saturn I turned over one of its three cards. It said Success, so the Saturn lit and ran properly, putting my gear into orbit. I returned the card to the set of three, face-down again, and shuffled. At this point I knew there is at least one Success card in the Saturn’s deck, but nothing else. Each time you use something you turn over a card, and if you use it multiple times on the same maneuver (e.g., you have two rockets ganged together to double your thrust) you turn over a card, return it, reshuffle, then turn over again. So you never get a complete picture of what’s in that technology’s deck, and that makes for some pretty toe-curling draws. For big missions you might turn over cards for a dozen maneuvers, any one of which can stick you.

This risk-laden technology-based build concept is the heart of Leaving Earth and it’s unlike anything I’ve seen in other games. Although I recognize slices of it from other places its gestalt in this title is pretty wild. Some things just work, and you get complacent depending on them in spite of not knowing exactly how close to the edge you’re living. Other things are snakebit from day one, as my buddy Chris found out when he tried to rendezvous in space. He had one major failure after another. Now, the game gives you the opportunity to tune your technology, by paying $5 million to remove whatever card you just turned over. So Chris spent the money on his first failure (a major one that scrubbed the mission and left his cosmonaut stranded in space) to remove that one card. Now he could draw from only two. On his next attempt another major failure appeared, and he spent $5M again to clear himself down to just one card. Attempt 3 – Success! His Rendezvous technology had just one card left, and it was a Success. It cost Chris time and money, and he lost pace on his mission because of it, but now he knew he had Rendezvous down cold and could depend on it. Not only that, but he could sell the technology to me at a premium, because when I bought it from him (with his 1 card on it instead of 3) I got to take the technology and put only 1 random-draw card on my copy as well. The rules on this barter concept didn’t seem particularly important on first read. But burning off those cards, even Success cards, has value. Trading between players is permitted as are outright sales, so Chris’ Rendezvous technology had additional value because he had beaten it into shape, down to just one card. Had he beaten it down to zero it would be automatic success for him AND for all who bought it from him. More dollars for him to plow into other tech and hardware.

We made plenty of mistakes and I needed to think more broadly regarding Rendezvous in order to make the distances while keeping weight down. You don’t need to carry your return-to-Earth rockets down to the Moon’s surface with you if you can rendezvous with them in Lunar orbit afterwards. As I figured that out with help from my fellow player Sam, I felt sheepish that I hadn’t thought of it myself. I had seen NASA use that exact same strategy when I was a kid. But in spite of our bumbling first turns in a game that offers a lot of options for creativity we got it done, with all of us coaching each other on how to make our stuff work better. It was competitive play, but cooperative for first-time players so that all of us could discover the ins and outs together. My contribution to the crazy ideas was to bring a couple of additional small thrusters on the way to a Moon Sample Retrieval mission, allowing me to have a minor failure in one (which I did) but still complete the job.

I'm the one on the right with steam coming off the top of my head. Plenty to think about and there's a time pressure, but it's likely that your buddies will go too early and blow something up too. There's time to iron things out before going for the big run.

I'm the one on the right with steam coming off the top of my head. Plenty to think about and there's a time pressure, but it's likely that your buddies will go too early and blow something up too. There's time to iron things out before going for the big run.

This game is all cards and tiles, but it's big on the table, big in the brain, and took a fair amount of time for us four noobs. We likely took twice as long as we will next time, but we all wanted "bigger" missions for our next session as well so I think we'll go back up to a three hour play even though we'll get more done. We started around 8 and finished at 11, but the time went quickly. There’s so much to think about and the nature of the game is that you can skip over players that are deep in thought if you’re in the process of taking care of little things. We’re all accustomed to starting our turns early and finishing them late to keep gameplay going, something which may or may not be kosher in your group. With that kind of genteel action at the table the game moves along well until someone goes for a big shot at something. And when they do, damn, it’s worth stopping to watch, because the Russians are sending Andrei Mikoyan to land on the frikkin’ Moon before NASA does! Let’s see if they can pull that shit off!

I've become really particular in my gaming tastes over the last few years, and Leaving Earth is a nice fit. Plenty of room for things to go wrong, and there's a way to hone your technologies to prevent that as the game progresses. My one buddy Chris had a train-wreck getting his Rendezvous to work, but he’s a guy that knows how to make things work. He got it done as did all of us. Really a very different play, one where things sometimes just ain't fair, but you takes whats you gets and finds your ways to make it work. There’s plenty of time for everyone to have something blow up, all part of pushing yourself hard to get there before the other guy does.

There’s additional unknowns in the game as well, in the form of multiple tiles for each goal location that represent things NASA and its competitors didn’t know as they stepped out into space. The Moon we drew at random had no special effects associated with it. But it could be fifty feet deep in dust that swallows anything landing on it, adding another way things can go pear-shaped. A peek at the cards reveals legit issues NASA contended with – can a human swallow in space? Can you land on the Moon without sinking? For anyone that’s listened to the recording of Apollo 11 landing on the Moon you hear Buzz Aldrin say “we’re kicking up a lot of dust” as they’re about to put down, not as a point of interest for the people in TV land but as a final piece of data for the scientists to digest if he and Neil were never heard from again. These complications can result in some missions being impossible, or some having very interesting twists. The game forces you to make contingencies all the time.

That’s my kind of gaming.

It’s a small package with nice art, virtually all cards, thin (but fully sufficient) cardboard tiles, flat wooden pieces that represent your ships on the board and one die that you use for exactly one purpose. The die is an odd piece in a game so driven by driven by card draw, perhaps a relic from earlier design concepts that were revised before printing. But the added draw for me personally is that one of its big features is real science and real history. This game manages to be chromy as hell with just a bunch of cards and a few flat wooden pieces. The box is small. There’s likely a dozen games on Kickstarter right now with seven pounds of plastic in them wishing they were as thematic and emotionally engaging as this.

Leaving Earth is a little hard to find, but there are copies kicking around. I got mine in trade for my copy of Silent Victory. The game is due for a reprint, and the base game comes with what used to be the first expansion. It includes Mercury and Venus, Mars, the asteroid Ceres and of course the Earth and Moon. Other expansions are out there for the outer planets and space stations, but I’ll tell you what – there’s plenty in this first package to have yourself a serious dose of rewarding brain-burn with moments of tragic hilarity sprinkled in at no additional charge. Our post-game show was good, based not only on what we had experienced during the game, but from the revealing of all the cards on our technologies as well. I had Saturn rocket from early in the game and had used it five times with one minor failure and four successes. When I turned over the cards I found a Major Failure that I had avoided by dumb luck. That put things in perspective. Sometimes you’re lucky, sometimes you ain’t. I won by two points. Oh my.

S.

Games

Games How to resolve AdBlock issue?

How to resolve AdBlock issue?