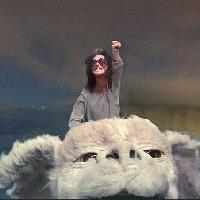

You remind me of the babe...

While playing River Horse's Labyrinth Adventure Game, my kids came upon a nursery encounter wherein Madame Aloe, a matronly plant, needed help to quiet some rowdy saplings and get them to bed. They came up with a pretty good plan- they’d sing a lullaby to them, in hopes that they would capture their attention and they would drift off to sleep.

“What are you going to sing them?” I asked.

My daughter looked me straight in the eye and sang “dance, magic dance, magic dance.”

Of course, the saplings went totally nuts and it turned into a musical number which included playing the Bowie song on my phone. And of course, it worked and tired out the plants so they went to bed. Madame Aloe was greatly impressed and offered passage. It was one of those perfect gaming moments, a rare instance where everything lines up and is pitch-perfect, capturing the setting, tone, and narrative exactly right. Moreso because it was a moment that felt absolutely true to the Jim Henson classic upon which this ultra-light role-playing game is based.

I fell in love with this book as soon as I touched it. It’s exquisitely illustrated with new Froud drawings, and it is packed with tons of two page encounters – many designed by Ben Milton (of Questing Beast fame) with additional guest spots by Patrick Stuart (Deep Carbon Observatory), Matt Ward (Warhammer), and others. Surreal, whimsical, hilarious, weird and wonderful, these encounters will take players (led by the refereeing Goblin King) through a magical journey to the heart of the Labyrinth. It’s extremely rules light – almost to a fault – and it is very reliant on a “be creative” impetus. No prep is required, the characters don’t even have stats, and you don’t even have to bring your own dice. Two are included in a space cut out in the book itself.

Players may choose one of the proscribed character types, mostly based on those seen in film. You can be a worm, a dwarf, a Knight of Yore, or a Horned Beast. Or, you can be the strangest of all – a human. You can even be a goblin. Or, you can be anything else you want. This is a very open-ended game, which most will find either liberating or intimidating. The remainder of character generation is simple – you determine a couple of things your character is good or bad at and in a rather Oz-like turn, what the group wants from the Goblin King should they reach their castle at the center of the great maze. There really aren’t any numerical stats, and the only real administrative measurement of import is time.

The dice system is based on the difficulty class and advantage/disadvantage concepts, but using a standard D6 roll for resolution. If something improves a roll- say, an advantaged position, trait, or a tool – then you roll two and take the high number. A hindered roll, of course, finds you rolling 2D6 and taking the low roll. The encounters are filled with opportunities for all sorts of tests, and the focus is on role-playing, puzzle solving, and creative solutions rather than combat or conflict. It almost feels like violence is discouraged – which is not an unwelcome tone to strike with this setting.

The encounters are mostly great, with lots of fun situations that could be resolved in any number of ways depending on the players’ imaginations. Everything my group has played through has been delightful- we’ve seen Goblin balloons, dwarves spraying the hedges for fairies, Brick Keepers, Junk Ladies, and a mysterious creature in the dark that actually kind of spooked my kids until its true nature was revealed. There are plenty of random tables to help inspire and guide the Goblin King, as well as a small bestiary with plenty of unique and unusual denizens.

Progress through the encounters is somewhat random, with die rolls advancing the players to the next encounter as the previous one is completed. Sometimes there are bonuses to push forward a little faster. There is a sense of time pressure, especially later in the game, if the players have dawdled or have found themselves delayed for whatever reason. But really, a good Goblin King is going to let the players get to the center and see what happens from there rather than let them fail out in the Labyrinth. But don’t tell the players that.

Now, here’s the thing. Even though this book is supremely accessible, I find that it is unusually demanding particularly for those who may not be used to OSR (old school renaissance) style systems that favor squishier rulings over hardline rules. There aren’t many rules at all, and some may find themselves scratching their heads at how to resolve situations without guidance or how to develop narrative encounters on the fly. Indeed, improvisation is essential and those who put hours and hours of time into prepping their 5e games may be on the back heel when they are given just a page of setup, a random table, and about two minutes to work the characters into it all, creating a cohesive and consistent story environment. Players used to writing out pages and pages of boring backstory to discuss with their DMs may be shocked to find that their character is expected to emerge through decisions, actions, and interactions during play. Quite frankly, as it should be.

I play OSR games almost exclusively now and I am accustomed to this kind of improv, off-the-cuff play where player actions are the defining story element but even so, I found myself oddly stressed out playing the Goblin King. I can’t count the number of times where, in retrospect, I wish that I had handled something differently or where I came up with a better idea later on. I think players coming in from heavier RPGs are going to feel that the capital G-Game is too slight and those new to RPGs are going to be intimidated by how much of the creative work is put on the players and the Goblin King. You’ve got to have players that are willing to dig in and construct the world and its parameters as they play, and that’s a tall order for some

Fortunately, I’m the right kind of referee for this game and the folks I’ve played with have been the right kinds of players. We can roll with a sentence or a bit of text and spin something from that from a random table. The games I’ve played have been really fun, even if they’ve been oddly stressful and rather dependent on my improv skills.

Regardless, I love this book and I love having it in my RPG collection. I think the format and layout are outstanding, and I wouldn’t mind seeing other adventure games using this same structure. The two page encounters are well written and sometimes brilliant with charming riddles and simple puzzles, and I like that I can draw a map or diagram of each on an index card quickly to set up a scene and get everyone right into the next bit of the story. The tables, bestiary, and other administrative level stuff are all uniformly excellent and inspiring.

But, there again, you have to be willing to use this book as a tool rather than as a gospel. To be honest though, interested players could just as easily use any desired RPG system to play through this game if the included rules are too vague or not structured enough. I’ve thought about using Into the Odd or Ben Milton’s Knave to give it a little more heft, but it’s really up to you. As the book suggests, every Goblin King is different, every Labyrinth is different. It’s only make believe.

Games

Games How to resolve AdBlock issue?

How to resolve AdBlock issue?