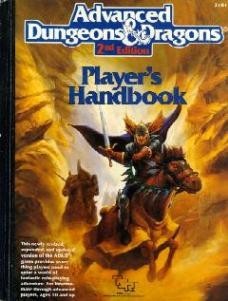

Every week I take part in something that would have seriously troubled many of the people with whom I grew up. I set up a cardboard shield with a big picture of people fighting a dragon on the front. I unload a stack of hardcover books, gather a couple sets of polyhedral dice, and take on the role of Dungeon Master. My friends and I have been working through the Dungeons & Dragons module Tomb of Annihilation. It's one of the highlights of my week. I'm a Christian, and I play Dungeons & Dragons.

Such a juxtaposition would have been highly controversial thirty years ago, and in some circles I suppose it still is. In the 1980s, the fundamentalist wing of Christianity waged an all-out war on D&D. Even today, I don't typically let on about my hobby with everyone I know. This is less because of shame and more because I just don't think it's worth the trouble to have to explain it. But the truth is that my caution is largely unwarranted. In the last five years or so, Dungeons & Dragons has experienced its most widespread acceptance in history. Between an accessible new edition, numerous streaming shows like Critical Role, and a wider pop culture profile in shows like Stranger Things, D&D is officially mainstream. That acceptance extends to those from a Christian background who might have balked at association with the world's biggest roleplaying game. So what changed? How did D&D beat fundamentalism?

(Full disclosure: my own experience is largely with the Christian response to Dungeons & Dragons, since the moral panic in the 1980s was largely driven by that faction. I am less familiar with how other faith traditions responded to D&D, or indeed how they respond now. I would be extremely interested in hearing more about this, however.)

Before we go any further, it is worth pointing out the most obvious reason: the fears held about D&D were bogus to begin with. While people like Jack Chick, Pat Robertson, and Patricia Pullman stoked the fears of D&D as a source of satanism and demon-worship in the 1980s, even some secular sources, like Phil Donahue, got in on the action. For these people, Dungeons & Dragons was not just a spiritual risk, it was a mental health issue. What would we do about all of these kids, suckered into satanic cults that wanted them to eventually commit suicide or kill other people? The version of D&D conjured by these fears is so unrelated to what the actual game is like that it's almost impossible to refute such charges. For those who are still worried, I assure you that the game is basically make-believe with a whole lot of rules.

But there have been some strong cultural changes in the last thirty years that have basically killed this war. For one thing D&D itself changed. The cultural conception of fantasy has shifted in the last few decades. As originally conceived by Gary Gygax and Dave Arneson, Dungeons & Dragons reflected a fantasy world that to us today looks rather amoral. It was less about heroes fighting evil than it was about all kinds of people just getting sweet loot. This subgenre of fantasy, usually called "sword and sorcery," gradually gave way to more heroic stories. For a great example of this latter kind, you can look to Star Wars. While George Lucas set that story in space, it's fantasy to the very core. There are knights, princesses, and kindly old wizards. It's good versus evil, full stop. This is the kind of fantasy favored by the most visible example of the genre before D&D: the works of J.R.R. Tolkien. Gygax himself was less interested in this type of fantasy than in things like Conan the Barbarian and the works of Michael Moorcock. This more amoral fantasy world was more prone to moral panic, because it simply didn't draw as sharp a distinction between good and evil.

This sword-and-sorcery mindset would largely be abandoned by Dungeons & Dragons. As early as 2nd Edition, the game became more explicitly about heroic characters fighting great villains, and less about loot. This was partially a conscientious decision, but I think it was also a result of the game becoming more story-based. Certainly after Wizards of the Coast took over the brand in the late 1990s, and after the Lord of the Rings books were turned into blockbuster movies, heroic fantasy was simply more mainstream. You can still play a morally gray loot-based game, but since just about every published adventure in the most recent edition is about characters defeating an evil villain, the transformation seems to be complete.

There's also a pervasive weirdness to early editions of D&D. This is partially a result of the less polished ruleset, the handdrawn illustrations in that first verion of the Monster Manual, and a loose lore that cheerfully stole from all kinds of folklore and fantasy tropes. This weirdness as steadily been smoothed out as the game has gotten older, undoubtedly a result of the transition to heroic fantasy, and the general homogenization of any product line that gets old enough. Those who desire the old-school weirdness now have old-school games to play, titles like Dungeon Crawl Classics. No game as old as D&D goes through so many corporate hands and remains that woolly. The version we have today is far more palletable to sensitive parents and those unused to the stranger aspects of the older editions.

Of course, D&D has had a deep influence on culture that never really stopped. That influence is especially pronounced in game design, both in the explosion of RPGs that followed it, and in basically all fantasy gaming. There are lots of kids who played games like Knights of the Old Republic, and never realized they were using the d20 system, designed for D&D's 3rd Edition. I knew plenty of kids who would never be allowed to play D&D, but somehow got into the Warcraft series. Of course JRPGs like the Final Fantasy games primed the acceptance as well, as did all of the tabletop roleplaying games that followed D&D. I had friends in high school who played Middle-earth Roleplaying, something that none of our evangelical Christian parents batted an eye at.

But there are two big cultural milestones that made it perfectly acceptable for not only Christians, but pretty much everyone to get into D&D: the Lord of the Rings movies, and the Harry Potter franchise. Gygax's distaste for Tolkien aside, he stole shamelessly from The Hobbit and Lord of the Rings. Tolkien's work remained highly influential and well-loved for decades, but the movies made epic fantasy a highly lucrative prospect. Now we live in a world where you're weird if you aren't into wizards and dark lords, and the LotR movies are the Big Bang to that universe. Along with The Chronicles of Narnia, The Lord of the Rings has for decades been the go-to fantasy series for young Christian readers. The crowd-pleasing Peter Jackson films gave those bookworms sudden common ground with a huge chunk of popular culture, and I think that common ground has gone both ways. Just as the wider acceptance of fantasy led to a wider acceptance of D&D in broader culture, so it did the same in Christian culture.

Still, I think it is actually the Harry Potter series that has proven to be the biggest game-changer. This is for two main reasons. First of all, the book series inspired its own little moral panic, and it completely steamrolled the opposition. Not only were the Harry Potter books not nearly as evil as the fundamentalists made out, but they have numerous Judeo-Christian themes that are so overt it's hard to imagine that people were upset in the first place. The books and movies proved that moral panics are almost always paper tigers. I have a hunch that the Harry Potter series is among the most-read series in American church youth groups.

Secondly, the Harry Potter books primed young people for a certain kind of fantasy that was favored by D&D. This was a world filled with magic, with lots of little clues and plot hooks that would eventually wrap into the characters in meaningful ways, and paid off years down the road. Harry Potter is about mystery more than anything else, and its simple setup-and-payoff structure is Dungeon-Mastering 101. To this day, I am convinced that the most reliable indication that someone would love tabletop roleplaying is if they love the Harry Potter books.

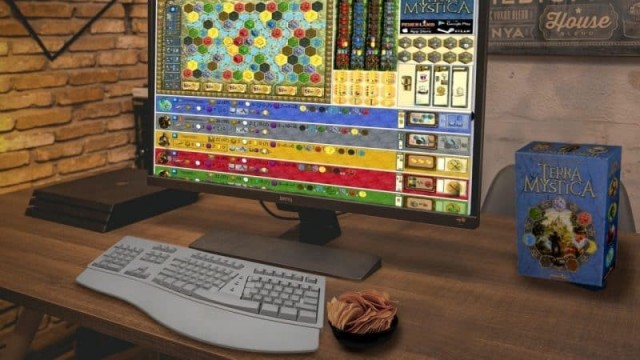

Of course, we are now dealing with a couple of other factors that have made Dungeons & Dragons a cultural monolith again. The first is the 5th Edition of the game, which is highly accessible and intuitive, particularly in contrast to 3rd and 4th Editions. It was the right game at the right time. The world of streaming games has also dispelled the mystery surrounding the experience of playing D&D. It's hard to tell explain the roleplaying experience, but these days an explanation is only a Youtube video away. It is now obvious that the game does not consist of evil incantations to summon demons. Rather it's about inside jokes, rules arguments, and those wonderful moments where everyone, DM included, is surprised and delighted by the experience of shared storytelling. This renewed relevence of D&D has not been met by a fresh moral panic. Either because of greater acceptance or ignorance of the new trend, fundamentalism has not mounted a fresh attack in the face of the new golden age of Dungeons & Dragons. The wizards won.

The victory of D&D over fundamentalism is not yet complete, but the war is definitely over. This is a good thing, because for faith-based communities who worry about worldly influence, D&D is actually a terrific hobby. It pulls kids and teens away from their phones for a few hours a week, and encourages them to swim in the deep waters of imagination and creativity. It is an opportunity to demonstrate serventhood and collaboration. The game is only good when we are willing to bear with each other and be honest about our expectations, when we are concerned about the enjoyment of others as well as our own. Those are values that everyone could stand to learn, and I'm glad that the stigma of playing D&D is dying from religious circles.

Games

Games How to resolve AdBlock issue?

How to resolve AdBlock issue?