It is December, 1984.

The sky is a gray slate, the air damp and cold. But I am aglow with excitement. As an 11 year old, newly-minted gamer I am about to visit my first proper game shop. It's a little way out of the Norwich city center streets I know, so my Dad guides me, eyes rolling with loving exasperation.

At school, a friend has told me what to expect. There will be racks of games and miniatures in "blister packs". I ask my friend what this is: he explains the figures come in plastic stuck to cardboard. In my empty 11-year old head I imagine a little plastic bag stapled to corrugated card. It doesn't seem an exciting way to package what is, for me, about the most exciting thing in my small world.

We turn the corner away from the city center and into a fairy wonderland. There are cobblestones beneath my feet, smooth and wet with the moist air. The shop fronts are higgledy-piggledy gingerbread. There is an old bench around an even older tree that gives the street its name: Elm Hill.

It's like stepping back in time. The shops sell tiny things from a bygone age: old stamps, dolls, tea and cakes on patterned translucent china plates. In the sea of wonders, I almost miss the games shop, its treasures hidden behind steamed up windows. Above the door, in small gothic lettering, is emblazoned a legend: The Games Room.

My Dad lets me go inside while he waits in the cold. I am so consumed with excitement that I barely notice the man behind the counter is greeting me. The shop is small and smells of forgotten treasures. There are bookshelves filled with rule books and magazines that I have, until now, only read about. Atop glass cases are whirly stands on which hang the blister packs. And now I understand they are not plain bag and card but branded, coloured, their precious contents safe behind a hard protective shell.

I browse the racks with the concentration of a scholar poring over an ancient text. Eventually, I select a purchase: it's a figure of an orc, shield in one hand, sword in the other, the blade resting on its shoulder. Later, I will take it home and paint it red because I have no idea orcs should be green and I will have a big argument with my friend about it. But for now, I hand over my weeks' pocket money to the man behind the counter.

He introduces himself as Duncan and carefully counts out my change. I step out of the door into the cold street, money clutched in one hand and figure in the other, little knowing I have also stepped through a trapdoor into a pit I'll be falling down for decades.

--------------------

It is December, 1989

The sky is a gray slate, the air damp and cold. Laughing with my friends, I turn the corner into to Elm Hill. The cobbled streets and timbered houses are of no interest now, lost behind a wall of ribald jokes, video games and the first sticky thrusts of romance. We go straight to the shop and open the door, consumed with the lust of acquisition.

Duncan greets us all. We're semi-regular visitors, although we spend a lot more time in the seaside arcades and the computer game shop in the main street. I don't know if he remembers us, but he's always polite, always full of enthusiasm and advice. One of our party starts rambling about the optimisation plan for his latest character, and he listens with patient interest.

I go into the back room. It's messy and the smell of damp is stronger. It's almost like a storeroom, and I wonder for a moment if I'm supposed to be here. Then I see that among the boxes and peeling plaster there are some games on display, and I relax. On one side there is something I've never seen before: thin paper pamphlets, printed in faded, shaky typeset.

The first one I pick up bears the legend "Harvest Time" and a crude picture of a man with a bow on the front. I rudely interrupt Duncan and my friend to ask what it is. He explains it is a "fanzine", a magazine written and printed by the collective enthusiasm of a local game group. Later I will take it home and plan my own fanzine and I will have big arguments with my friends over what to put in it.

I have more money to spend now, acquired from a part-time waiting job. So I hand over some of my pay packet to buy Harvest Time and another amateur printing, a set of tabletop wargame rules to use with plastic tanks. Duncan carefully counts out my change. I step out into the street, little knowing the fanzine in my hands will inspire me to try games writing for myself, and one day to a professional career.

--------------------

It is December 1996

The sky is a gray slate, the air damp and cold. I am taking the long-suffering lady who will one day be my wife on a tour of my hometown, over 200 miles from where the two of us now live. We've come to Elm Hill to en route to the Cathedral, and she's not expecting such archaic wonder. She stops to look in all the shop front, cooing with delight at the buildings and their contents. Of course, it's a great excuse to drag her into The Games Room.

Having moved away it's been a couple of years since my last visit, but Duncan says hello and it's like seeing an old friend again. The shop is now full of collectable card game boosters alongside the figures and boxed games but has otherwise barely changed.

At this point my focus is Warhammer: we'd passed a Games Workshop on the high street on my way here. Duncan, it turns out, isn't all that keen on the new Games Workshop after the management buyout. I propose to him that it's good to get new kids into the hobby, but he's unconvinced. He thinks they'll just play GW product and nothing else. He's gloomy about his prospects.

In deference to his feelings, I select a couple of miniature blisters I know will look seamless in my Vampire Counts army and look round the shop. In a wall-mounted display is a new game I've heard of but never seen before. It's called "Settlers of Catan". My future wife picks it up and reads the back. "Sounds fun. You should get this," she says, in innocence of the old beast she's stirring in my soul. Later, we will play it and have a small argument about whether we should play it again.

So I do. I'm paying out of a student loan this time, but Duncan seems to need the business to I buy the figures and game together for a tidy sum. He seems a little more upbeat as he counts out my change. I step out into the street, little knowing I'm carrying a box that will forever change the way I - and many others - view gaming as a hobby.

--------------------

It is December 2017

The sky is a gray slate, the air damp and cold. I've dragged my two daughters up to Norwich before, between visits to relatives, to see the Castle Museum. But today, with their lengthening legs and attention spans, I'm taking them to Elm Hill. As we turn the corner, they gasp their astonishment. They've never seen cobbles or such old buildings in all their short lives. It's been far longer than those lives since I've been to this shop. I'm wondering how it's going to feel to be reliving their age again.

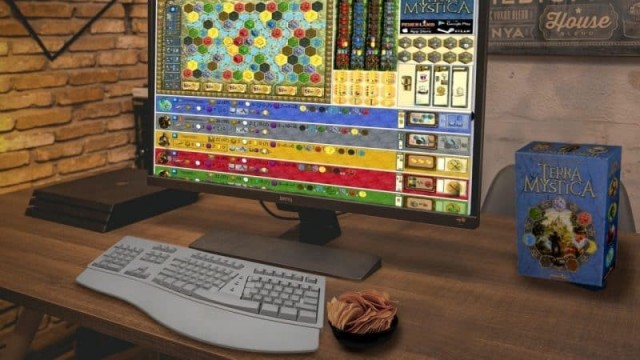

The shop is still there. It still smells the same. All that's changed is the stock: there are still role-playing books and figures but now every surface has been piled high with board games. The culprit stands behind the counter, older, but still radiating enthusiasm. He looks up to say hello as we enter then pauses, squints and frowns. "I know you," he says. It feels like being remembered by a national institution.

He chats patiently, amiably to my kids. At one point they mention I'm a games writer now and I mumble "thanks partly to you" to Duncan. I'm wandering around the shop, picking up boxes, feeling the weight, listening to the contents shift. It's a million miles away from snipping sellotape on a mail order parcel. It's lovely, but it's not the nostalgia rush I was expecting.

To my disappointment, he has nothing I want in stock. With my home already groaning with underplayed games, I don't want to buy anything on a whim. So, seeing the kids are getting fed up, I make to leave. "But you must buy something," complains my eldest. "What about this," says the youngest, pointing to a game with a cute Panda on it. It's called Takenoko. I've heard it's good, and I know I'll never hear the end of it if I don't, so I grab it and take it over to Duncan.

Being an engineer and a writer now, I pull out a credit card and Duncan's face falls. He doesn't take them. But that's okay: I have enough cash. And as I hand it over and he counts out my change, quite suddenly, there it is: that flood of childish glee I'd been hoping for all along. A repetition of an action I've taken a hundred time before, over twenty years ago, and it all comes rushing back. Later, we will play the first game we all jointly chose and have a fantastic time.

I step out into the cobbles with a spring in my step that wasn't there before, heedless of the gathering gloom. We all three are laughing and joking and I marvel that such a simple affair can bring such joy. The game is a happy weight in my hand. Only one thing mars the moment: I wish I'd said my thank you with more clarity, show Duncan how his shop has been a small but vital part of making me the man I am.

Thank you, Duncan.

Games

Games How to resolve AdBlock issue?

How to resolve AdBlock issue?