Gamers have packed into the hall, the noise and heat are unbelievable. I am too tired to cope with the sensory overload, but I am drawn to the lady with purple hair like a beacon of hope in midst of chaos. As the evening passes, that hair will serve as an anchor in a sea of geekery, enabling other friends to find and speak to us. I know the lady with the purple hair and her friend have a game waiting for me and, tired as I am, my hopes are high.

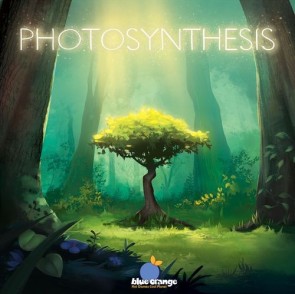

As I approach, I see them picking pieces out of a box, assembling little cardboard trees. I know this: Photosynthesis. Not particularly on my radar but I am here and there is a seat. It would be rude not to.

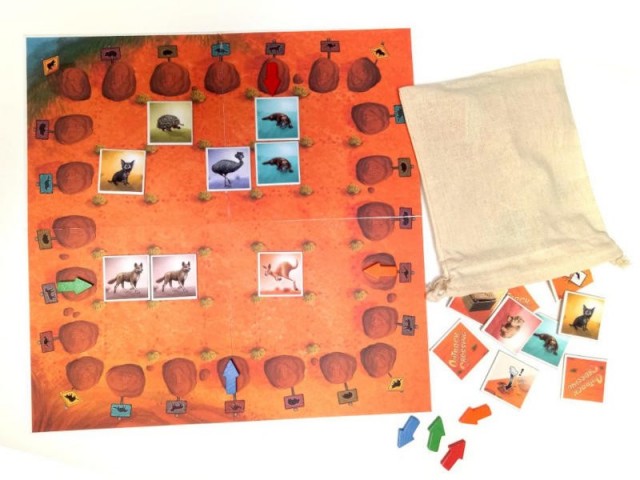

My trees are blue, which offends the biologist in me. I start out with mere seeds and have to grow trees through three height stages by paying for them in sunlight. To get sunlight, you need trees and the bigger your trees the more sun you get. To win, though, you need to chop trees down and chip them into points, depriving you of light. This is a negative feedback loop, which is much better biology. Its near circularity begins to stoke the interest of my exhausted brain.

The board show concentric circles. You start on the outside, but the closer you get to the centre, the more points you get. Right away it seems clear that racing for the middle is a good idea, so I do. I cough up light and gain seeds in return. As the initial turns pass, and the actual cardboard sun begins to orbit the board, I plant the seeds and grow the trees. My little copse grows toward the middle. It gets there first.

My tree that eventually grows in the middle of that forest doesn't make any noise. But it does end up annoying the living hell out of everyone.

See, like in a real forest, Photosynthesis is a race for light. As trees grow and the sun shifts, taller trees block light from shorter ones. As well as reducing your income, it means the little trees can't escape by growing that turn, so it's a double whammy. But even though the fat, jolly paper sun marks quite clearly where the light shines each turn, I cannot force my tired brain to see it.

"So I get one, four ... eight light," I confidently rack up on my play board. "No, NO," come the patient replies, every turn pointing out that I've forgotten this tree or that tree that's starved of light and life. This cannot stand. If you can't beat them, join them. So I grow my tree in the middle. It takes a while because taller trees on the outer circles keep restricting its like. But in time it grows as big as it can go, ready for felling for maximum points.

And I leave it there.

Not only does this mean no-one else can harvest prime points. It also means that every single turn that tree is casting a two-space shadow away from whatever direction the sun is facing. It's blocking light in all the second and third best spaces around it. Everyone wants me to cut it down. You only get two full-height trees to play with, so leaving it there hampers me from gaining points elsewhere.

But I like it. It is a good tree, tall and strong and handsome. It dominates the board. Its size means it can spread seeds far and wide. Best of all, it annoys my opponents.

Slowly, the game unfolds in its shadow. In spite of the shade rule, it's not the most interactive thing. But somehow the life in the game seems to bring the life out of the players. Even me, my tiredness forgotten. We plan our turns aloud, peering at the cardboard forest and measuring wood. Eventually, I sacrifice my favourite tree in the name of victory, which makes me sad. As the sun rises and falls, it illuminates plans we didn't see coming. By the time it is setting, we can already the winner in its shadow. That's a shame, but the dance was wonderful.

In the silence and sanctuary of home, I teach it to the children. There's a family version of the game for them, with fewer rounds and no blocking. They love the sturdy cardboard trees, the way the forest spreads its tendrils over the board in glorious three dimensions.

As expected, this is a tamer game, but the race for light still proves engrossing. Even at their young age, they appreciate how everything locks logically together like the branches of a tree. Leaves make light, light grows leaves, leaves get sacrificed for points. There are deliberate component limitations to enrich the strategy. But within that lovely, living triangle of ideas, they feel harsh and artificial. Without randomness, it's possible we could strip off the cardboard bark and count the mathematical rings inside. But that would seem cruel, somehow, like stripping leaves off a sapling.

The sun is shining on the patio and winning hardly seems to matter. Photosynthesis doesn't take long to play, but it feels slow, hypnotic, like watching the breeze ruffling the boughs outside. As though someone had invented a form of Chess made softer, somehow, but still with a tough, hardwood core. As I put the cardboard shrubs back into the box, I'm struck by the irony of a game about tree-felling made out of felled trees. I look up at the firs marring the sunbeams at the top of the garden and decide that their sacrifice has been worthwhile.

Games

Games How to resolve AdBlock issue?

How to resolve AdBlock issue?