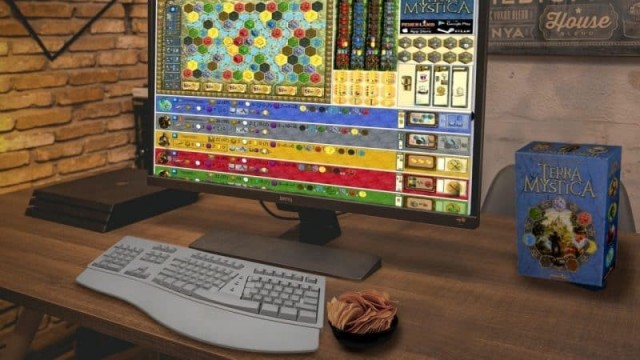

Introducing Jonathan Volk- our new writer with a killer take on one of the best games of all time.

Dune is an impossible book. I mean this with great admiration: the book is grandly operatic, densely philosophical, a thrill to read. It is also corny as hell, filled with clunky internal speech delivered in breathless italics, overly long like most mass-market paperback sci-fi, and impossible—the book has eluded all attempts to successfully adapt it for the screen, and will likely do the same for Denis Villeneuve’s upcoming adaptation (after the costly disappointment of Blade Runner 2049, you have to wonder how producers could look at Dune and anticipate a box office “rebound”).

Between Jodorowsky's ludicrous failure to adapt the film in the 1970s, Lynch's decision to film it instead of Return of the Jedi in the 1980s, and the SyFy (then SciFi) channel's slavishly faithful rendition, previous attempts at adapting Dune have ranged from melodramatic soap, to stupendously lavish, to laughably camp, to bizarrely cheap and to, well, not ever actually made.

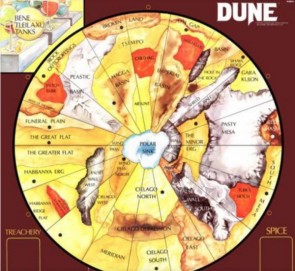

Though Dune has eluded adaptation to the screen, it has been, since 1979, an impeccable strategy/war game with heavy negotiation and economic elements. Adapted by the EON design team and published Avalon Hill, Dune puts Arrakis on the game board as a slice of the southern hemisphere, seen from above the Polar Sink. The map is divided between desert and non-desert zones, cities and vague geographical regions (my favorite, “The Minor Erg”, has no “Major Erg” neighbor). The game accommodates 3 to 6 players (though it is best at 6), each choosing between factions that include the houses Atreides (reliably good), Harkonnen (reliably evil), and the Padishah Emperors (boring in the way of all entrenched power); the Spacing Guild, a satanic melange of Uber and Silicon Valley venture capitalism, who handle all transport to and from the planet; the Fremen, the planet’s indigenous people, because the novel is also a parable of Vietnam-era Capitalist-Imperialism; and the Bene Gesserit Sisterhood, space zealots, also referred to as witches, whose motives are femininely unknowable, because the book was written by a man in the 1960s.

You may also like this review of the new board game from Gale Force Nine.

The goal of the game is territorial control: fill key areas of the map before your opponents. To that end, each faction comes with a set of powers that allow it to break core mechanics of the game. For example, the Bene Gesserit can “co-exist” rather than fight with other players in all zones of the map; the Fremen get to ditch the Spacing Guild’s monopolistic Ubers and book sandworms instead, demonstrating, in the process, how infrastructure, and access, is at the heart of most warfare.

Despite the success of the adaptation, Dune is an impossible game - out of print and impossible to buy, outside of re-sale markets like eBay. It is only truly excellent when played with 6 players, meaning you need to do the equally impossible and convince five others to devote half a day to playing a game with Ergs, ornithopters, and spice blows (“A spice blow means you’re doing it wrong,” said a friend who doesn’t know Dune-the-book, hates Dune-the-film, but ended up loving the Dune-the-game).

Dune is also impossibly good, better than any board game I’ve played, and I’ve played a lot of them. I think the key to Dune’s success is that it makes unfairness a seductive point of entry. Designers call what I’m calling unfairness “asymmetry”, a fancy word that fails to encompass the moral dimensions of great game design. The narrative space of Dune situates its players immediately in a set of moral crises—invasion, monopolistic overreach, religious conversion. And the game’s mechanics affirm these crises immediately: the Emperor player starts outrageously wealthy, able to finance an immediate and punishing invasion; the Spacing Guild player will come to amass outrageous wealth through her stranglehold on infrastructure; the Bene Gesserit Sisterhood don’t occupy space with the same weight as their more masculinely-coded enemies, opting instead for a ghostly co-existence, like a silenced wife (more on that below); the Fremen guerrilla units move quickly around the desert, but systemic poverty and their functional absence from the galactic market means they either need to win the game as early as possible, or draw play out to an unbearable 15 turns (the Fremen “win” if nobody else holds a winning condition).

So many games assure players that the table has an Arthurian circularity, that all seats are distanced equally from the table’s eye, and that no single player has a better seat. But no game is universally fair, because all players sit at the table with different levels of experience, capability, play-styles, goals, lusory attitudes. More recent war games, like Twilight Imperium, have heard of Dune but don’t seem to have listened to its lessons, failing to make their factions so wildly imbalanced, so teetering and wobbly, so morally compromised and enabling. Dune spits in fairness’s face. The beginning turns of the game are an outrage for the Fremen and Bene Gesserit players, the two factions widely agreed upon to be the most difficult to play. This is why teachers of Dune typically opt to play as the Bene Gesserit or the Fremen—how do you persuade a new player to play a game they are, by design, rigged to lose? In 5-player games, popular wisdom encourages erasing the Bene Gesserit entirely from the map, affirming what we already know—in space, nobody can hear a woman scream.

But these murky moral dimensions, reified by the unfair mechanics, are what make Dune a masterpiece. In an interview on the podcast Ludology, Peter Olotka, one of the three credited designers, scoffs at the pursuit of fairness in games. Olotka says, “Fair isn’t funny. When everything’s fair, where’s the outrage? Where’s the laugh? Where’s the ‘Wow, I overcame it?’ It was all fair, and I muddled my way to a victory over 17 hours, moving my piece one spot. For us, […] that’s the point. […] The idea of balance is […] a false god in game design. Balance is, you know, balance is for weenies.”

In addition to Dune, Olotka co-designed Cosmic Encounter, the grandfather of asymmetrical game design, and the way he describes fairness as an antidote to comedy seems right, since fairness is a softer grab for justice, and justice isn’t funny business. No, Dune, and certainly Cosmic Encounter, are unfair to a degree that you either laugh at with the blinking resignation of a habitual sufferer, or it disgusts you into never playing again.

I’m not certain every game of Dune I’ve played has been fun. That would be a damning statement for most games, especially those that require the commitment of Dune (4+ hours minimum). But no game lingers with me more than Dune. I haven’t even mentioned how, if the Bene Gesserit player correctly guesses the winning faction of the game and the round said faction will win, the Bene Gesserit win the game. This almost happened to me—once, as the Bene Gesserit, I predicted the winner but was off by a round. The likelihood of the Bene Gesserit player pulling off this victory condition is incredibly small, all the smaller because the Bene Gesserit can only do so much to shift the balance of power in the game toward their prediction. But the lesson is a 1979 parable for real-world moral crises, even in 2018: though it still happens too rarely, a woman’s voice can take down a rotten Emperor.

Like the novel, Dune the board game isn’t explicitly feminist by any means, though a fan-made DIY version of the game’s artwork, credited to the artist Ilya Baranovsky and available online, goes a long way to depicting both men and women with respect and dignity, and is absent the dehumanizing male gaze found in Twilight Imperium, the Fantasy Flight intellectual property that would eventually re-skin Dune as Rex: Final Days of an Empire. In Twilight Imperium, the one faction coded as exclusively female, the Nuala Collective, are depicted as sexy snakes with tits. In Rex, the Bene Gesserit have been translated into sexless turtles - a lateral move at best.

Like war films, war games are suspiciously deficient in the point of view of women, as if the second the first keel slides onto foreign shore, all women in theaters of combat blink out of existence. That Dune offers the Bene Gesserit player an exclusively female point of view can be read as a mild admission to the inequity of representation—mild, because the Bene Gesserit powers are still coded according to feminine stereotypes, whether through mind-control via the Voice or the strategic self-erasure of co-existence. Call this the creaky burden of faithful adaptation. As in the novel, any step forward through the desert is a dangerous business when you have giant, ancient phalluses in the form of sandworms salivating to devour you.

But I want to return to Olotka’s claims about fairness. Can a board game be moral in the way of a novel, a film, a play? That is to say, can a board game deliver a coherent moral message about our relationship to suffering (our own and others’) and still be fun to play? Games do a great job, I think, of presenting moral crises as the occasion for engagement, leaving players to figure out what the Right Thing To Do (RTTD) is. For most players, the RTTD is to win, damn whatever sins get you across the finish line. The RTTD in games is usually victory-oriented rather than morality-oriented (though these can overlap), which makes games fun but morally dubious. This must be part of their broad appeal: we get to try on amoral styles of being that otherwise repulse us.

Games, whether we're talking the likes of Dune or Undertale, have the ability to game-ify moral quandaries, and this quality can lead us to question our relationship with games, morality, and the larger culture around us. Games can be open systems, engaged with the culture that produces them, despite their closed rules and artificial conflicts.

Unlike the binary morality often present in, for example, many video games, Dune lets players perform in the drag of morality and amorality to a degree of complexity I find astonishing. Most other games feel fairer in comparison, and less interesting because of it. Board games like Dune can muddy their moral dimensions precisely because they have the advantage of being social. Human players don’t always do the rational, strategically best thing for themselves—the RTTD might, in the moment, blur between ethics and victory points. The Fremen player, in desperate need of money, might still align herself, ruinously but morally, with the Bene Gesserit, seeing in her witch-sisters a community of shared suffering. I’ve seen this happen, and I’ve done it myself—not to spite other players, or to throw the game, necessarily, but to chase after some ghostly feeling of the RTTD beneath the RTTD. If this all sounds suspiciously like my lusory attitude with gaming is more that of a role-player than a rational strategist, maybe that’s right. Though I love to win, winning, in the end, doesn’t always feel lovely. Depending on the outcomes, the methods used to reach those outcomes, the gameplay process, subject matter and other factors can make winning feel disappointing or sometimes even wrong.

In my experience, with my group, games of Dune are rarely even played to resolution so that there isn't even really a nominal winner. As I said, the game is impossible—it usually goes on too long, and at too great a psychic and physical cost. If you make it to round 10, most players’ combat units will be left floating in the embryonic purgatory of their respective Bene Tleilaxu Tanks (mobile space wombs). As the war for Arrakis sputters forward, the economic, moral, and bodily costs affect even those hegemonic factions afforded structural and economic power. The Emperor begins the game filthy rich with fearsome combat units but usually can’t bankroll an invasion by round 11; the Spacing Guild amasses great wealth by turn 11, but one disastrous attempt at invasion sets him back, and now all his clients can’t afford to call him up for an Uber. Learning from the Fremen, the other players will grab their damn thumpers and walk (without rhythm) instead.

The film director Francois Truffaut famously critiqued war films by saying that to “show something is to ennoble it”. Truffaut believed that most war films fail to capture the horrors of war because they are exciting, digestible, fun to watch. Dune comes the closest to an anti-war war game that I’ve played. It makes me want to play more games that bring in the outside world, that make me feel injustice in a palpable, teachable way. We play games for many reasons, obviously, but I’m most interested in play as a vessel for social critique and resistance. In their exhaustive book Rules of Play: Game Design Fundamentals, Katie Sales and Eric Zimmerman define play as resistance as follows:

“Play never merely resides in a system of rules, but through an ongoing process of friction, affects change in the system. The friction of water flowing against rock and earth over time will alter the more rigid structure of a riverbed. Similarly, when we frame a game as a system of resistance, the very play of the game is intrinsically transformative [italics are mine]. This transformation not only takes place on the level of rules but on cultural levels as well, as the resistance creates tensions between the magic circle and the contexts surrounding the game.”

Transformative game designs like Dune’s dilate the Arthurian circularity of our gaming tables. They invite the world to take a seat. Play feels so impossibly real. If you backstab your friend and say, “Hey, it’s only a game,” she can say, “You really are a bad person.”

Games

Games How to resolve AdBlock issue?

How to resolve AdBlock issue?