The excellent Michael Barnes recently conducted an excellent interview with game designer Reiner Knizia. He's widely regarded as one of the best game designers ever, but his stock has gone up and down around these parts. Currently, it's up: something I didn't realise when I waded in to offer a contrary opinion.

The response begs an interesting question: what do we mean when we say "best" in this context? What qualifies a designer for an epithet of "great"?

I'm in a poor position to judge, having designed one godawful game in my entire life, which has never seen the light of day. But as a critic, I'm supposed to offer opinion on such things. So here we go.

What's always impressed me most about new designs is creativity. Board gaming is inherently limited by the things you can do with card and wood, metal and plastic. It's straitjacketed by thousands of years of human tradition which leads us to expect games to look and play a certain way. Breaking away from these strictures as the massive weight of cultural expectation bears down on you must be unbelievably hard.

Genre-shattering designs are correspondingly rare. Genre-shattering designers, who manage the feat regularly, are even more so. And by that measure, Knizia doesn't measure up.

One of the moments when conventions got splintered to pieces was the mid-nineties when early German-style games hit the UK and America. These games are great games: great then, and still great now. Titles like Settlers of Catan and El Grande were like nothing we'd ever seen before. Their designers were rightly celebrated for that achievement, although they've not hit such heights again.

Knizia was not quite a part of that moment. He rode on its coat tails, with his best games appearing in the late nineties. That shows in his designs. Lost Cities and Battle Line are clear Rummy variants. Samurai and Through the Desert trace obvious lines of descent to classic abstracts. Modern Art and Medici are just fancy auctions.

This trend, of taking tried and tested mechanics and twisting them into interesting new shapes, is almost a hallmark. It takes a lot of skill, and Knizia has more skill than most. What it doesn't take is a lot of creativity.

You could also argue that he's almost earned himself black marks against innovation by using his immense talents to churn out cookie-cutter games. His output is prodigious, focused on the German family market with titles few of us will have heard of, let alone played. But far too many look a lot like re-skinned or tweaked versions of his existing games. That's surely the opposite of creativity.

His cleverest inventions, to my mind, are his Egyptian games Ra and Amun-Re. They contain the seeds of genius. But I'm not sure two clever titles qualifies a designer for the innovation hall of fame.

His most celebrated title is Tigris and Euphrates. It's not a design I'd say was particularly creative, owing a huge debt to common abstracts. It's also not a game I enjoy particularly, although I can see why people do. It's a strong, lean and deep design one could play many times and still not master.

Which leads us on to another consideration. What if you don't measure a designer by their creativity, but by a simpler measure: how much people enjoy their games?

Here, the good doctor is on much firmer ground. He's got eight games in the boardgamegeek top 200, a spectacular feat considering that they're older titles in a list which favours newness and celebrity. Some of those games, particuarly Battle Line and Ra, belong to that rare category of games that offer joy to almost everyone.

So I'm guessing that fun is the criteria people are using when they talk about Knizia being a great designer. One could argue, again, that his vast output of mediocre titles should be set against this highlights, but perhaps that's a churlish attitude.

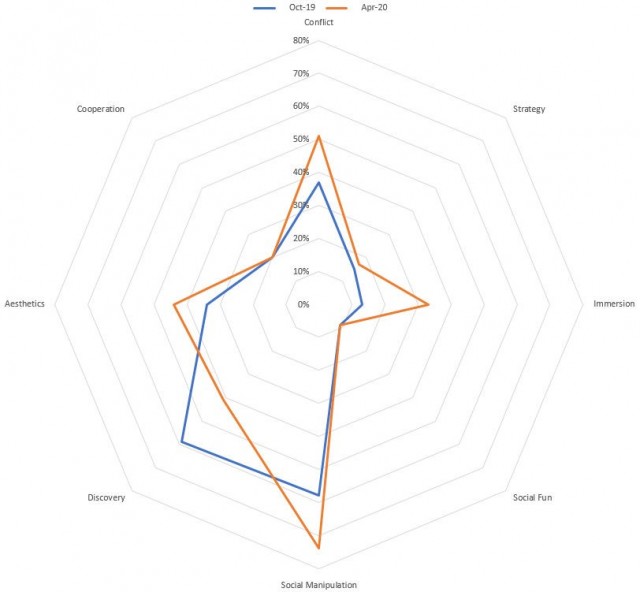

What's more troubling is that some of his more popular games are amongst his most tedious. Samurai and Through the Desert strike me as humorless, boring games that would be better played against a machine than a fellow human being. The fact that these are celebrated would once have seemed to some as evidence of everything that was wrong with gaming. It still does to me, but it seems I'm now in a minority.

I'd argue, though, that creativity is simply a better measure of greatness. It's rarer, for starters. Since that mid-nineties explosion of German brilliance I'd say there are perhaps three people who've shown it regularly. They are Martin Wallace, Rob Daviau and the incomparable Vlaada Chvatil.

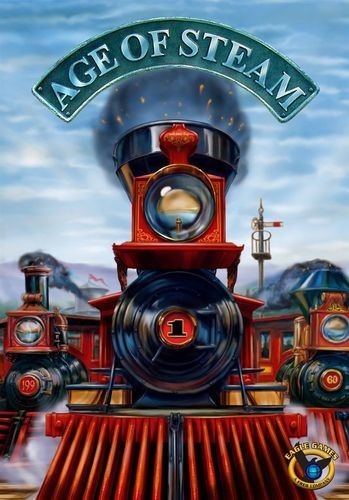

On the other side, of that triumvirate, it's only Chvatil who's regularly put out games that are both creative and fun. Daviau's designs are often packed with fresh imaginative ideas, but the execution leaves something to be desired. Wallace perfected the art of bringing balance to highly interactive and non-random games, but his titles can be dry and heavy beyond endurance.

And this is where Dr. Knizia earns his stripes. Not as the most creative designer ever, nor as the most fun, but as someone who's struck a beautiful balance of the two with so many of his games. When you step back there are remarkably few designers whose work is almost always worth your time in some way or other. I still think Vlaada is top of that heap. But Knizia wins a deserved second.

Games

Games How to resolve AdBlock issue?

How to resolve AdBlock issue?